Introduction and Contexts

- Faulkner At Virginia: Introduction

- Faulkner in the Late 1950s

- The US in the Late 1950s

- Virginia in the Late 1950s

Faulkner in the Late 1950s

In February 1957, when he arrived in Charlottesville to occupy his position as the University of Virginia’s first

Writer-in-Residence, William Faulkner was 59 years old. Over the previous 34 years he had published sixteen novels, five volumes

of short stories and about a dozen other books, but had only recently begun to wear the label by which he would often be

introduced during his two years at UVA: the country’s – sometimes the world’s –

“greatest living novelist.” In 1949 he became just the fourth American author to win a Nobel Prize for Literature; this was his most prestigious honor,

but earlier in the same year the American Academy of Arts and Sciences awarded him the Howells Medal for Fiction, and in the next

five years he also received two National Book Awards (1951, 1955) and a Pulitzer Prize (1955).

In February 1957, when he arrived in Charlottesville to occupy his position as the University of Virginia’s first

Writer-in-Residence, William Faulkner was 59 years old. Over the previous 34 years he had published sixteen novels, five volumes

of short stories and about a dozen other books, but had only recently begun to wear the label by which he would often be

introduced during his two years at UVA: the country’s – sometimes the world’s –

“greatest living novelist.” In 1949 he became just the fourth American author to win a Nobel Prize for Literature; this was his most prestigious honor,

but earlier in the same year the American Academy of Arts and Sciences awarded him the Howells Medal for Fiction, and in the next

five years he also received two National Book Awards (1951, 1955) and a Pulitzer Prize (1955).

After decades of worry about money, during which he repeatedly needed to go to Hollywood to work on salary as a screenwriter,

by the mid-Fifties his own fiction had finally made him financially secure; for example, now Hollywood came to him, buying the

rights to novels like The Sound and the Fury for much more than they’d ever made as books. (Both The Tarnished Angels, adapted from Pylon, and The Long, Hot Summer, based on The Hamlet, would be released in 1958 during his second UVA term;

he was asked to comment on the second

After decades of worry about money, during which he repeatedly needed to go to Hollywood to work on salary as a screenwriter,

by the mid-Fifties his own fiction had finally made him financially secure; for example, now Hollywood came to him, buying the

rights to novels like The Sound and the Fury for much more than they’d ever made as books. (Both The Tarnished Angels, adapted from Pylon, and The Long, Hot Summer, based on The Hamlet, would be released in 1958 during his second UVA term;

he was asked to comment on the second

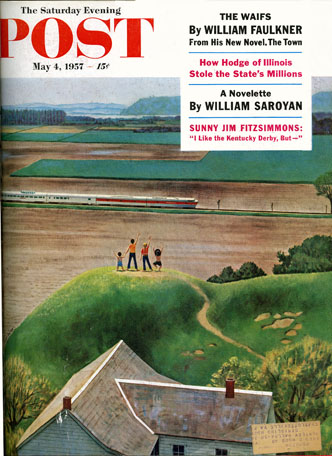

, but not the first.) Right before he arrived in Charlottesville to begin his first term in residence, Faulkner learned that

The Saturday Evening Post had bought the episode from The Town called “The Waifs” for

$3000, the largest price he had ever received from a magazine. (In April 1957 he read this story to the Jefferson Society.)

, but not the first.) Right before he arrived in Charlottesville to begin his first term in residence, Faulkner learned that

The Saturday Evening Post had bought the episode from The Town called “The Waifs” for

$3000, the largest price he had ever received from a magazine. (In April 1957 he read this story to the Jefferson Society.)

Faulkner had usually been reluctant to leave Mississippi during the decades in which he wrote most of his Yoknapatawpha

fiction, and had to acquire a passport in 1950 to go to Stockholm to accept his Nobel Prize. But in the years after that trip he

became something of a frequent flyer: he went to England, France, Norway, Italy, Switzerland, to Egypt, Brazil, Japan and the

Philippines, to Iceland. (During the Spring semester, 1957, he became the writer-out-of-residence for two weeks when he traveled to Greece on a State Department sponsored tour that coincided with the

opening in Athens of a dramatization of Requiem for a Nun. He was very moved by his experience of Greece

Faulkner had usually been reluctant to leave Mississippi during the decades in which he wrote most of his Yoknapatawpha

fiction, and had to acquire a passport in 1950 to go to Stockholm to accept his Nobel Prize. But in the years after that trip he

became something of a frequent flyer: he went to England, France, Norway, Italy, Switzerland, to Egypt, Brazil, Japan and the

Philippines, to Iceland. (During the Spring semester, 1957, he became the writer-out-of-residence for two weeks when he traveled to Greece on a State Department sponsored tour that coincided with the

opening in Athens of a dramatization of Requiem for a Nun. He was very moved by his experience of Greece

. At the end of his 1958 term, however, he declined a State Department invitation to travel to the Soviet Union, because, he

said, it was a totalitarian state.)

. At the end of his 1958 term, however, he declined a State Department invitation to travel to the Soviet Union, because, he

said, it was a totalitarian state.)

And if he had earlier seemed reclusive, during the Fifties he decided to play a more public role in the nation’s and

his region’s affairs. In 1956 he accepted President Eisenhower’s invitation to be the Chairman of the

Writer’s Group in the People-to-People program that the administration launched as a public relations counterattack to

what was perceived as the Soviet Union’s international propaganda campaign. He also took it upon himself to speak out

about the racial tensions and conflicts that were growing in the South as Jim Crow segregation was being challenged and defended

in courtrooms, schools and the streets. From Light in August (1932) to Absalom, Absalom! (1936) to Go Down,

Moses (1942) to Intruder in the Dust (1948), his fiction had almost steadily become more preoccupied with the

legacy of slavery and the injustices of racism. There are passages in Intruder that some critics have seen as Faulkner

using the pages of his novel as a platform from which to directly address to his contemporaries about relations between black and

white, and between South and North. Beginning with a letter in 1950 to the Memphis Commercial Appeal about a white man

who was convicted but not executed for murdering three black children, Faulkner started speaking in his own name, on his authority

as a Mississippian, about civil rights and wrongs. Before taking up his post at Virginia, he published three articles on the issue

in national magazines: Life, Harper’s and even Ebony. (His Life piece,

“Letter to the North,” was reprinted in a UVA student publication

during his first term in residence. During his 30 May 1957 session with the public, a member of his all-white audience asked

Faulkner what advice he had given in the Ebony article “to the colored people” about “the

way they should act toward integration”

And if he had earlier seemed reclusive, during the Fifties he decided to play a more public role in the nation’s and

his region’s affairs. In 1956 he accepted President Eisenhower’s invitation to be the Chairman of the

Writer’s Group in the People-to-People program that the administration launched as a public relations counterattack to

what was perceived as the Soviet Union’s international propaganda campaign. He also took it upon himself to speak out

about the racial tensions and conflicts that were growing in the South as Jim Crow segregation was being challenged and defended

in courtrooms, schools and the streets. From Light in August (1932) to Absalom, Absalom! (1936) to Go Down,

Moses (1942) to Intruder in the Dust (1948), his fiction had almost steadily become more preoccupied with the

legacy of slavery and the injustices of racism. There are passages in Intruder that some critics have seen as Faulkner

using the pages of his novel as a platform from which to directly address to his contemporaries about relations between black and

white, and between South and North. Beginning with a letter in 1950 to the Memphis Commercial Appeal about a white man

who was convicted but not executed for murdering three black children, Faulkner started speaking in his own name, on his authority

as a Mississippian, about civil rights and wrongs. Before taking up his post at Virginia, he published three articles on the issue

in national magazines: Life, Harper’s and even Ebony. (His Life piece,

“Letter to the North,” was reprinted in a UVA student publication

during his first term in residence. During his 30 May 1957 session with the public, a member of his all-white audience asked

Faulkner what advice he had given in the Ebony article “to the colored people” about “the

way they should act toward integration”

.) Though his UVA audiences several times raise the topic of race in his work or the Supreme Court’s ruling, it

seems to have been entirely Faulkner’s idea to use the pulpit of his residency to speak out about integration.

“A Word to Virginians,” delivered on 20 February 1958 at the start of his second term as Writer-In-Residence

to about 350 white people, was perhaps the climax of Faulkner’s efforts to influence the course of the Civil Rights

Movement. By then the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v Board of Education (1954) had led to an escalating

series of confrontations over integrating the schools, Martin Luther King had emerged as the eloquent and determined leader of the

forces working for change, and the defense of segregation had provoked more and more extreme measures, from a bombing in Clinton,

Tennessee, to Virginia’s plan to close its public schools rather than integrate them. In Faulkner’s various

pronouncements on this issue there are occasionally extreme moments too, and 21st century readers will probably see him as a

racial conservative, even a racist, but he saw himself as a moderate who knew blacks could no longer be denied their rights as

people and citizens but who also knew the white South would resist orders coming from “outlanders,” by which

he meant the North

.) Though his UVA audiences several times raise the topic of race in his work or the Supreme Court’s ruling, it

seems to have been entirely Faulkner’s idea to use the pulpit of his residency to speak out about integration.

“A Word to Virginians,” delivered on 20 February 1958 at the start of his second term as Writer-In-Residence

to about 350 white people, was perhaps the climax of Faulkner’s efforts to influence the course of the Civil Rights

Movement. By then the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v Board of Education (1954) had led to an escalating

series of confrontations over integrating the schools, Martin Luther King had emerged as the eloquent and determined leader of the

forces working for change, and the defense of segregation had provoked more and more extreme measures, from a bombing in Clinton,

Tennessee, to Virginia’s plan to close its public schools rather than integrate them. In Faulkner’s various

pronouncements on this issue there are occasionally extreme moments too, and 21st century readers will probably see him as a

racial conservative, even a racist, but he saw himself as a moderate who knew blacks could no longer be denied their rights as

people and citizens but who also knew the white South would resist orders coming from “outlanders,” by which

he meant the North

. Privately during the late-1950s Faulkner helped pay the tuition of two African American students at black colleges.

Publically his comments played very little role in the deepening crisis. Northern liberals dismissed them as temporizing

apologetics for an indefensible system. But many white Southerners considered them a betrayal of his homeland; even as he was

being more acclaimed around the world, he felt increasingly alienated from his neighbors in Oxford, including most of his closest

relatives. According to his biographers, his status as almost a pariah in the Deep South probably increased his willingness to say

Yes when the UVA English Department invited him to move to Charlottesville, though it may also have made University President

Colgate Darden wary about approving that offer.

. Privately during the late-1950s Faulkner helped pay the tuition of two African American students at black colleges.

Publically his comments played very little role in the deepening crisis. Northern liberals dismissed them as temporizing

apologetics for an indefensible system. But many white Southerners considered them a betrayal of his homeland; even as he was

being more acclaimed around the world, he felt increasingly alienated from his neighbors in Oxford, including most of his closest

relatives. According to his biographers, his status as almost a pariah in the Deep South probably increased his willingness to say

Yes when the UVA English Department invited him to move to Charlottesville, though it may also have made University President

Colgate Darden wary about approving that offer.

According to the record, Darden was unenthusiastic about bringing Faulkner to the grounds. Another cause of his uneasiness may

have been the writer’s well-founded reputation as a drinker. His only previous invited visit to UVA occurred in 1931,

when he was asked to participate in a conference for southern writers; during the conference, whenever Faulkner did show up for a

scheduled event, he had been unmistakably, amazingly drunk. He still regularly struggled with his attraction to alcohol. A spree

in New York in February 1957 had landed him in the hospital for three days immediately prior to the start of his first term as

Writer-in-Residence, and twice during his two semesters at UVA he was similarly hospitalized to recover from the effects of

binging. His drinking was one indication of Faulkner’s troubled life during his years here. His daughter Jill was

married to a UVA Law student, and the longing he shared with his wife Estelle to be near their first grandchild played a major

role in his decision to come to Charlottesville, but inside even this immediate family there were long-standing tensions. Unlike

his visit in the Thirties, as Writer-in-Residence Faulkner fulfilled all his duties to the University, including keeping daily

office hours and attending and sometimes hosting social functions, but the evidence indicates that despite all the rewards that

had finally come to him, in the late Fifties Faulkner was still haunted by the “demon” that, he said, drove

every good writer..

According to the record, Darden was unenthusiastic about bringing Faulkner to the grounds. Another cause of his uneasiness may

have been the writer’s well-founded reputation as a drinker. His only previous invited visit to UVA occurred in 1931,

when he was asked to participate in a conference for southern writers; during the conference, whenever Faulkner did show up for a

scheduled event, he had been unmistakably, amazingly drunk. He still regularly struggled with his attraction to alcohol. A spree

in New York in February 1957 had landed him in the hospital for three days immediately prior to the start of his first term as

Writer-in-Residence, and twice during his two semesters at UVA he was similarly hospitalized to recover from the effects of

binging. His drinking was one indication of Faulkner’s troubled life during his years here. His daughter Jill was

married to a UVA Law student, and the longing he shared with his wife Estelle to be near their first grandchild played a major

role in his decision to come to Charlottesville, but inside even this immediate family there were long-standing tensions. Unlike

his visit in the Thirties, as Writer-in-Residence Faulkner fulfilled all his duties to the University, including keeping daily

office hours and attending and sometimes hosting social functions, but the evidence indicates that despite all the rewards that

had finally come to him, in the late Fifties Faulkner was still haunted by the “demon” that, he said, drove

every good writer..

At the same time, summing up his two terms in his final public event, he says that “Faulkner was happy”

living in Charlottesville

At the same time, summing up his two terms in his final public event, he says that “Faulkner was happy”

living in Charlottesville

. As Writer-in-Residence, he published The Town in the Spring term, 1957, in time for it to become a topic

in some of his UVA sessions, and began writing The Mansion; this third volume of the Snopes trilogy was not completed

until his second term was over (it was published in November, 1959). During the two Spring semesters of his official residency, he

spoke to at least 37 different audiences – mostly students in classrooms, but also the larger University community and

the local public, local high school students, faculty from other colleges, the

English Department faculty, the Department of Psychiatry, the wives of Law School students and the press. He claims to have

learned to enjoy these sessions, and (as Joseph Blotner’s memoir makes clear)

also enjoyed his extra-curricular time with the UVA Track team. But his greatest enthusiasm while he was in residence seems to

have been for “riding to the hounds.” The Albemarle County gentry were numerous enough to support two fox hunt

clubs – Farmington and Keswick. Faulkner became a member of both, and despite some falls, including one that broke some

ribs, worked hard to perfect the art of jumping a large horse over a fence line in the costume of an English aristocrat. As his

second term drew to a close, his admirers in the English Department asked the University to offer him a permanent adjunct

position; President Darden refused, overtly on the grounds that doing so would lead to similar expectations on the part of future

Balch Writers-in-Residence but perhaps because of either Faulkner’s unorthodox stand on segregation, or his drinking, or

both. Before Katherine Anne Porter replaced him as Balch Writer-in-Residence for 1958-1958 , however, he and Estelle had already

decided to maintain a residence of their own in Charlottesville; in 1959 they purchased a house here. Nor was the University ready

to let go of its connection with him. In January 1959 Alderman Library appointed him to be “consultant on contemporary

literature,” an honorary position that gave him an office on grounds for the upcoming Spring term. In 1960 he accepted a

“permanent” position as Balch Lecturer in American Literature in the English Department. In that role he again

appeared before UVA classes and public audiences in 1960, 1961 and 1962 (when his death put those quotation marks around

“permanent”), but as far as we’ve been able to discover, those sessions, perhaps half a dozen

altogether, were not recorded.

. As Writer-in-Residence, he published The Town in the Spring term, 1957, in time for it to become a topic

in some of his UVA sessions, and began writing The Mansion; this third volume of the Snopes trilogy was not completed

until his second term was over (it was published in November, 1959). During the two Spring semesters of his official residency, he

spoke to at least 37 different audiences – mostly students in classrooms, but also the larger University community and

the local public, local high school students, faculty from other colleges, the

English Department faculty, the Department of Psychiatry, the wives of Law School students and the press. He claims to have

learned to enjoy these sessions, and (as Joseph Blotner’s memoir makes clear)

also enjoyed his extra-curricular time with the UVA Track team. But his greatest enthusiasm while he was in residence seems to

have been for “riding to the hounds.” The Albemarle County gentry were numerous enough to support two fox hunt

clubs – Farmington and Keswick. Faulkner became a member of both, and despite some falls, including one that broke some

ribs, worked hard to perfect the art of jumping a large horse over a fence line in the costume of an English aristocrat. As his

second term drew to a close, his admirers in the English Department asked the University to offer him a permanent adjunct

position; President Darden refused, overtly on the grounds that doing so would lead to similar expectations on the part of future

Balch Writers-in-Residence but perhaps because of either Faulkner’s unorthodox stand on segregation, or his drinking, or

both. Before Katherine Anne Porter replaced him as Balch Writer-in-Residence for 1958-1958 , however, he and Estelle had already

decided to maintain a residence of their own in Charlottesville; in 1959 they purchased a house here. Nor was the University ready

to let go of its connection with him. In January 1959 Alderman Library appointed him to be “consultant on contemporary

literature,” an honorary position that gave him an office on grounds for the upcoming Spring term. In 1960 he accepted a

“permanent” position as Balch Lecturer in American Literature in the English Department. In that role he again

appeared before UVA classes and public audiences in 1960, 1961 and 1962 (when his death put those quotation marks around

“permanent”), but as far as we’ve been able to discover, those sessions, perhaps half a dozen

altogether, were not recorded.

Images from the Faulkner Print Collection —

Below: Faulkner in Stockholm, 10 December 1950, with novelist Gustaf Hellstrom and the President of the Nobel Foundation. Though he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950, the award was officially "for 1949." Courtesy the Faulkner family.

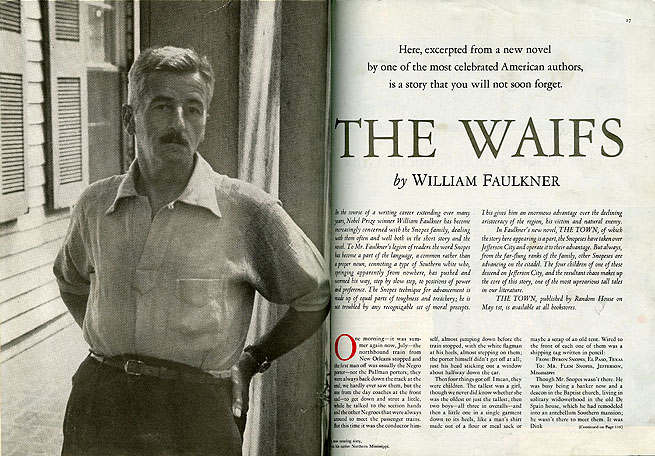

Below: (1) Cover from Saturday Evening Post (4 May 1957); (2) pages 26-27 of that issue. Caption: "William Faulkner, now nearing sixty, still lives in his native Northern Mississippi."

Below: U. S. State Department photograph of Faulkner in Japan, August 1955. Faulkner Papers, Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Below: four photographs by unidentified photographer of Faulkner in Greece, March 1957, from Faulkner Papers Photograph Collection [Prints # 0224 and 0225]. Captions on back, from top to bottom: "Foreign Minister Averoff, U.S. Ambassador George V. Allen"; "Ambassador Allen, Prince Peter"; "'Gavin Stevens' & 'Temple Drake' with WF, Greek production of Requiem for a Nun"; "WF at Univ. of Athens."

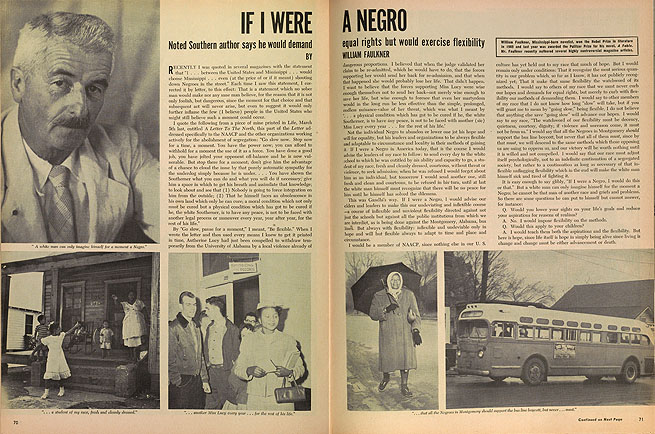

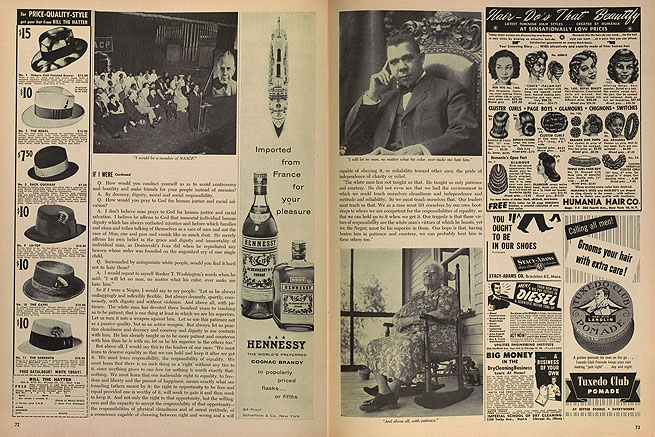

Below: (1) detail, cover of September 1956 Ebony magazine, (2) pages 70-71, (3) pages 72-73. The photographs illustrating Faulkner's article use phrases from the article as captions. The four across the bottom of pages 70-71 show (a) an unidentified black family, (b) Miss Autherine Lucy with white University of Alabama students, (c) and (d) two photos from the Montgomery bus boycott. The photograph on page 72 is of an NAACP meeting. The photos on page 73 are (a) Booker T. Washington and (b) an unidentified black woman.

The Virginia Spectator Jim Crow Issue (May 1957, vol. 118, no. 8, pp. 19, 29-30)

Letter to the North

By William Faulkner

WILLIAM FAULKNER, winner of the Nobel Prize and one of America's foremost authors, is currently at the University as a Writer-in-Residence, and this article was reprinted by permission of the author. Mr. Faulkner is the moderator in this issue's discussion.

MY family has lived for generations in one same small section of north Mississippi. My great-grandfather held slaves and went to Virginia in command of a Mississippi infantry regiment in 1861. I state this simply as credentials for the sincerity and factualness of what I will try to say.

From the beginning of this present phase of the race problem in the South, I have been on record as opposing the forces in my native country which would keep the condition out of which this present evil and trouble has grown. Now I must go on record as opposing the forces outside the South which would use legal or police compulsion to eradicate that evil overnight. I was against compulsory segregation. I am just as strongly against compulsory integration. Firstly of course from principle. Secondly because I don't believe compulsion will work.

There are more Southerners than I who believe as I do and have taken the same stand I have taken, at the price of contumely and insult from other Southerners which we foresaw and were willing to accept because we believe we are helping our native land which we love, to accept a new condition which it must accept whether it wants to or not. That is, by still being Southerners, yet not being a part of the general majority Southern point of view; by being present yet detached, committed and attainted neither by the Citizens' Council nor NAACP; by being in the middle, being in a position to say to any incipient irrevocability: "Wait, wait now, stop and consider first."

But where will we go, if that middle becomes untenable? If we have to vacate it in order to keep from being trampled? Apart from the legal aspect, apart even from the simple incontrovertible immorality of discrimination by race, there was another simply human quality which drew us to the Negro's side: the simple human instinct to champion the underdog.

But if we, the (comparative) handful of Southerners I have tried to postulate, are compelled by the simple threat of being trampled if we don't get out of the way, to vacate that middle where we could have worked to help the Negro improve his position . . . compelled to move for the reason that no middle any longer exists . . . we will have to make a new choice. And this time the underdog will not be the Negro, since he, will now be a segment of the topdog, and so the underdog will be that white embattled minority who are our blood and kin. These non-Southern forces will now say, "Go then. We don't want you because we won't need you again." My reply to that is, "Are you sure you won't?"

So I would say to the NAACP and all the organizations who would compel immediate and unconditional integration: "Go slow now. Stop now for a time, a moment. You have the power now; you can afford to withhold for a moment the use of it as a force. You have done a good job, you have jolted your opponent off-balance and he is now vulnerable. But stop there for a moment; don't give him the advantage of a chance to cloud the issue by that purely sentimental appeal to that same universal human instinct for automatic sympathy for the underdog simple because he is under."

And I would say this too. The rest of the United States knows next to nothing about the South. The present idea and picture which they hold of a people decadent and even obsolete through inbreeding and illiteracy – the inbreeding a result of the illiteracy and the isolation – as to be a kind of species of juvenile delinquents with a folklore of blood and violence, yet who, like juvenile delinquents, can be controlled by firmness once they are brought to believe that the police mean business, is a baseless and illusory as that one a generation ago of (oh yes, we subscribed to it too) columned poticoes and magnolias. The rest of the United States assumes that this condition in the South is so simple and so uncomplex that it can be changed tomorrow by the simple will of the national majority backed by legal edict. In fact, the North does not even recognize what it has seen in its own newspapers.

I have at hand an editorial from the New York Times of February 10 on the rioting at the University of Alabama because of the admission of Miss Lucy, a Negro. The editorial said: "This is the first time that force and violence have become part of the question." That is not correct. To all Southerners, no matter which side of the question of racial equality they supported, the first implication, and – to the Southerner – even promise, of force and violence was the Supreme Court decision itself. After that, by any standards at all and following as inevitably as night and day, was the case of the three white teen-agers, members of a field trip group from a Mississippi high school (and, as teen-agers do, probably wearing the bright, parti-colored blazers or jackets blazoned across the back with the name of the school) who were stabbed in passing on a Washington street by Negroes they had never seen before and who apparently had never seen them before either; and that of the Till boy and the two Mississippi juries who freed the defendants from both charges; and of the Mississippi garage attendant killed by a white man because, according to the white man, the Negro filled the tank of the white man's car full of gasoline when all the white man wanted was two dollar's worth.

This problem is far beyond a mere legal one. It is even far beyond the moral one it is and still was a hundred years ago in 1860, when many Southerners, including Robert Lee, recognized it as a moral one at the very instant when they in turn elected to champion the underdog because that underdog was blood and kin and home. The Northerner is not even aware yet of what that war really proved. He assumes that it merely proved to the Southerner that he was wrong. It didn't do that because the Southerner already knew he was wrong and accepted that gambit even when he knew it was the fatal one. What that war should have done, but failed to do, was to prove to the North that the South will go to any length, even that fatal and already doomed one, before it will accept alteration of its racial condition by mere force of law or economic threat.

Since I went on record as being opposed to compulsory racial inequality, I have received many letters. A few of them approved. But most of them were in opposition. And a few of these were from Southern Negroes, the only difference being that they were polite and courteous instead of being threats and insults, saying in effect: "Please, Mr. Faulkner, stop talking and be quiet. You are a good man and you think you are helping us. But you are not helping us. You are playing into the hands of the NAACP so that they are using you to make trouble for our race that we don't want. Please hush, you look after your white folks' troubles and let us take care of ours." This one in particular was a long one, from a woman who was writing for and in the name of the pastor and the entire congregation of her church. It went on to say that the Till boy got exactly what he asked for, coming down there with his Chicago ideas, and that all his mother wanted was to make money out of the role of her bereavement. Which sounds exactly like the white people in the South who justified and even defended the crime by declining to find that it was one.

We have had many violent inexcusable personal crimes of race against race in the South, but since 1919 the major examples of communal race tension have been more prevalent in the North, like the Negro family who were refused acceptance in the white residential district in Chicago, and the Korean-American who suffered for the same reason in Anaheim, Calif. Maybe it is because our solidarity is not racial, but instead is the majority white segregationist plus the Negro minority like my correspondent above, who prefer peace to equality. But suppose the line of demarcation should become one of the race; the white minority like myself compelled to join the white segregation majority no matter how much we oppose the principle of inequality; the Negro minority who want peace compelled to join the Negro majority who advocate force, no matter how much the minority wanted only peace.

So the Northerner, the liberal, does not know the South. He can't know it from his distance. He assumes that he is dealing with a simple legal theory and a simple moral idea. He is not. He is dealing with fact: the fact of an emotional condition of such fierce unanimity as to scorn the fact that it is a minority and which will go to any length and against any odds at this moment to justify and, if necessary, defend that condition and its right to it.

So I would say to all the organizations and groups which would force integration on the South by legal process: "Stop now for a moment. You have shown the Southerner what you can do and what you will do if necessary; give him a space in which to get his breath and assimilate that knowledge; to look about and see that (1) Nobody is going to force integration on him from the outside; (2) That he himself faces an obsolescence in his own land which only he can cure; a moral condition which not only must be cured but a physical condition which has got to be cured if he, the white Southerner, is to have any peace, is not to be faced with another legal process or maneuver every year, year after year, for the rest of his life."

[Faulkner's essay originally appeared in Life magazine.]

Below: Photograph by unidentified photographer of Faulkner in downtown Charlottesville with his daughter, wife and grandson. The image is dated 16 November 1957. From the Faulkner Papers (Slipcase V, I/7376); courtesy the Faulkner family.

Below: Photo by unidentified photographer from Faulkner Papers Photograph Collection [Print# 0066; Digitization# 000005731_0003]. Caption on back: "Faulkner jumping 'Powerhouse' at Grover Van Devender's point-to-point Buck Mountain Riding Club, Spring Show, May 15, 1960."

The Charlottesville Daily Progress 8 May 1957

Hard, Fast Rule For Writers: Truthfulness, William Faulkner Tells High School Students

Novelist William Faulkner told prospective journalists and writers at Albemarle High School this morning that the one "hard and fast rule" every writer must follow is truthfulness.

"I will never put on paper and release something that I do not believe is true," the Nobel Prize winner in literature said.

Faulkner spoke to two groups of about 60 to 80 students each at the high school's annual Careers Day program. The program brought representatives of about 30 fields to speak to the students.

Asked what the most important things to a journalist are, Faulkner said "Take it you have the grounding in grammar, what you need is the practice in people."

He said students should train themselves into "insight into people, to know why people do what they do," and "To catch people in action at the interesting point."

"People are capable of infinite change. That's what makes anyone want to be a journalist or writer, to write about people, because of the infinite variety," Faulkner said.

"Don't ever get over being curious, wanting to know what you didn't know yesterday," the novelist warned his audience. He listed things important for a writer as "never to judge people, to listen, to watch, to probe, wonder what is the truth behind this action . . . patience, compassion." He later added "one quality a writer has got to have is a demon. He's got to be demon-driven."

Worked in New Orleans

Faulkner said he had done newspaper work in New Orleans in his earlier writing days, but never with the intention of taking up journalism as a profession.

Asked how he got into newspaper work, Faulkner said "I like to write, and I lived in the French quarter there, and I would see strange things. . .and I began to write those pieces, and I sent them to the editor."

Other Commentary

Other Faulkner commentary:

On his education: "I didn't like school and I quit in the sixth grade. School in those days moved too slow for me . . . and I would have liked to have gone to a good college."

On style: "Any writer who has a lot to say, hasn't got time to bother with style."

On his own long sentence structure: It "comes from the constant sense that one has that he only has a short time before he is going to die."

On his own opinion of his best novel: "The Sound and the Fury" caused him "the most anguish and trouble" and was "the most beautiful failure."

On life: "It's best always to have something a little beyond our reach to work for; then you can always be happy."

©1957 The Daily Progress

Mr. Faulkner: Writer-In-Residence

By Joseph Blotner

[This essay was first published in The Virginia Quarterly Review (Spring 2001), then as a chapter in Mr. Blotner’s autobiography, An Unexpected Life (Louisiana State University Press, 2005). It is reprinted here with the generous permission of the Blotner family and VQR.]

It was just as well, for Fred Gwynn and me and our hopes for the University of Virginia’s Writer-in-Residence Program in 1955, that our memories of Charlottesville did not stretch back more than a few years. Others recalled a signal event in its cultural life more than two decades before. Ellen Glasgow, Virginia novelist and literary grande dame, felt that Southern writers like herself living in New York were kept from seeing each other by their isolation and the bustle of metropolitan life. She proposed to UVa. English Department head James Southall Wilson a gathering of 20 or 30 leading writers in some pleasant place where they could talk with each other. The president of the university endorsed the idea, and the resulting committee invited 34, including Thomas Wolfe, James Branch Cabell, and William Faulkner. Against his inclination and better judgment, Faulkner made one of the number on Oct. 23, 1931, eagerly awaited because of the publicity that had greeted his sensational novel Sanctuary.

Genuinely shy, and convivial mainly with a few friends and then only intermittently, he attended just a few of the sessions. His old friend and sometime mentor, Sherwood Anderson, later wrote, “Bill Faulkner arrived and got drunk. From time to time he appeared, got drunk again immediately, & disappeared. He kept asking everyone for drinks. If they didn’t give him any, he drank his own.” By the time for departure, Faulkner was glad to accept dramatist Paul Green’s offer of a ride to New York. This was the beginning of a journey by car and coastal steamer that would add to the lore of Faulkner’s drinking exploits before his circuitous return to Mississippi. Memories of these events were still green in Charlottesville in 1955. One of the journalists who wrote at length about the Southern Writers’ Conference was Emily Clark, and now it was her bequest that would be the linchpin for the return of its most spectacular participant.

Fred and I wrote to more than a dozen prominent writers, but we had very little money to offer, and some, such as Edmund Wilson and J.D. Salinger, said that they did not do that sort of thing. Some were doing it elsewhere. Others did not reply. When a friend of the English Department mentioned the plan to Jill Faulkner Summers, she said, “I think Pappy might be interested in that.” When Fred wrote to him in April of 1955, he indicated his interest and supplied a short list of his needs, including “a place to live and a servant to clean it.” When Fred and Floyd Stovall, our chairman, drove out to see him in April at Fox Haven Farm, where Jill and her husband Paul were living, Stovall said with some embarrassment that he doubted if they could raise $2,000. “Don’t worry about money,” Faulkner replied, “All I need is enough to buy a little whiskey and tobacco.” He agreed to come in the late winter and early spring.

The three of us on the Balch Commitee were delighted, and Floyd moved quickly. He urged the appointment to President Colgate W. Darden, a tall spare aristocrat, former governor of the state and a member of the DuPont family by marriage. “It would add prestige to the university,” Floyd said in summing up.

“The University of Virginia,” said Darden, “has sufficient prestige without William Faulkner.”

Floyd thought that Darden had obviously heard about Faulkner’s last appearance at the university. “I feel sure nothing like that will happen again,” he said reassuringly, and the president agreed to recommend his appointment as writer-in-residence for the second semester of 1956-1957.

In January I glimpsed him for a moment from the other end of the long, dimly-lit corridor when he made a brief visit to the fifth floor of New Cabell Hall. A small man, severely erect, he moved slowly, turning into Fred’s office and out of my sight. On February 15th he strolled the Lawn in tweed suit and overcoat and Tyrolean hat, casually trim and elegant. After a press conference in Cabell Hall with the journalists and photographers who had trailed him along the Lawn, he met with students and visitors in Fred’s graduate course in American fiction. The session began with questions about The Sound and the Fury. He answered slowly and carefully in his light, soft voice. Then he would look down at the desk, idly turning over a matchbox housed in a metal holder decorated with RAF wings. His calm belied his feelings. “I’m terrified at first,” he would say later, “because I’m afraid it won’t move.” But it did, and the hour passed quickly. He was more relaxed at its end and in a session with reporters. When one asked why he accepted the invitation, he answered, “It was because I like your country. I like Virginia and I like Virginians. Because Virginians are all snobs, and I like snobs. A snob has to spend so much time being a snob that he has little left to meddle with you, and so it’s very plesant here.”

Enthusiastic admirers of his work as Fred and I were, we formed a kind of silent cheering section. After his accepting this gambit, we were anxious that it should succeed. I had heard a number of authors’ question-and-answer sessions, but his were different, and they were reflections of both his mind and personality. He was articulate but not voluble, and he could tolerate silence as few people could. He had submitted to many interviews, and over the years he had developed a number of formulaic answers, often wry and funny, and often conveying the flash and brilliance of epigrams. But he also had a spontaneous phrase-making gift. Though he looked attentively at questioners, I had the sense of a distance which he imposed between himself and the rest of us. This appearance had been an unparalleled experience for me and Fred too. When I returned to my office after meeting another class, Fred stuck his head in my door. “I’ll go get Mr. Faulkner and we’ll have coffee in my office,” he said. Before I could compose myself, Mr. Faulkner walked in.

He had an extraordinary presence. As I thought about it later, I realized that he radiated power. It was the kind of effect attributed to great tenors and matadors. Here this perception came from a number of things: from knowing I was with the man who had created so many works of art and who had such a profusion of gifts, from his aura of calm and silence, and from knowing how withdrawn and sometimes irascible he was said to be. When Fred introduced me and Mr. Faulkner extended his hand, it was not a handshake but a handclasp, the hard firm grip of a man used to exerting pressure, as in training horses and grasping hand tools. He spoke softly and casually. “Morning, Gin’ral,” he said.

He appeared perfectly relaxed in Fred’s large, cream-colored office, waiting quietly while the steaming Nescafe cooled, lighting a pipeful of his strong, rich-smelling tobacco, a blend so distinctive that you could enter a room and recognize that he had been there. As we sipped, he answered questions slowly and politely, but he obviously felt no need to initiate conversation for the sake of any amenities. He had been cordial, but when he left, walking slowly down the hall, head up, eyes straight ahead, Fred and I sat down as we would have after exercise that had claimed all our attention. Then Fred apologetically explained Faulkner’s odd greeting to me. Remembering his stories about World War I, and trying to make conversation that might interest him, Fred said that he and I had both flown in World War II. When Faulkner had expressed quiet interest, Fred had said, out of a mixture of nervousness and attempted humor, “I’ll go get General Blotner and we’ll have some coffee.” So the strange greeting had been an attempt to use local informal names. He did not employ it again, and soon he was calling us by our first names. We had enjoyed being with him, but it would be some time before we would be easy in his company.

Relatively few students took advantage of the office hours he offered to hold. “I sat there,” he said later, “and answered questions that could have been answered by a veterinarian or a priest.” Our colleagues kept up a steady stream of requests for him to appear in their classes, usually when they had assigned his fiction. As the junior member of the committee, I helped Fred in setting up the schedule and escorting him to class. When Floyd Stovall had written him in November, he had offered the department as a barrier against engagements beyond his duties, and Faulkner had gratefully accepted. It fell to Fred and me to do most of the shielding. We did so gladly, with the sense of intimacy it gradually helped to produce. Only later would we realize this would not endear us to some, including a few of our colleagues, but we didn’t care. This assignment was worth any amount of resentment. Only gradually would we recognize what a stroke of good fortune ours had been.

It occurred to us that our duties included an obligation to others besides the writer-in-residence. There were the students and teachers who would come after us and would not have the chance to ask the author of The Sound and the Fury and Absalom, Absalom! about his work. One day Fred and I resolved that after time spent with him we would write down what he said. But when we compared our recollections, we realized that this wouldn’t work. We couldn’t be his friend, but secretly recording what he said when he had thought he was talking casually. Only a few of his remarks at universities had been recorded, and others which had been misquoted or quoted out of context had caused misunderstanding and hurt feelings. There was one thing we could do. Fred suggested to him recording all the sessions. He readily agreed, and so one of us would carry a bulky tape recorder to class. That year Fred and I wore raincoats, and this sight of two average-sized men flanking a smaller one and carrying an object in a case reminded some of sinister characters in adventure movies. When one observer mentioned us to Faulkner, he replied, “They’re doing pretty well. Next month I’m going to teach them to fetch and carry.”

There was no telling when or how that sharp wit would flash out. And he provoked humor in others as well, though now it was good-natured rather than acerbic, as it had been many years before when envious locals had called him “Count No ’Count.” One of my students was a talented caricaturist. Al Carlson sketched him as long-nosed and spindly, cuffs over his knuckles, a book under his arm, one hand resting on a broken column as he looked smiling ahead. When the editor handed him his copy of The Virginia Spectator, I watched the subject, himself a talented caricaturist, take it and slowly inspect the cover. His face flushed with soundless laughter that grew until he was overcome with the paroxysms of coughing of the inveterate pipe smoker. There were other symptoms of the growing attitude that semester toward the writer-in-residence, one of pride and affection. What he had called snobbery in the first press conference had translated into respect for his privacy, and pride at the presence of a world-class artist on the Grounds of the University of Virginia.

Because Fred’s duties as editor of College English placed added demands on his time, he tended to have less of Mr. Faulkner’s society than I did. Some mornings he might stop in at my office rather than his own and sit there while he checked his morning mail. Occasionally he would surprise me with a comment. He had told Professor Atcheson Hench that his mail seemed initially to come mostly from old ladies criticizing his remarks that Virginians were snobs. He could never tell what subject they might broach. One morning he opened a letter, read it slowly, and then refolded it. “This woman says how she likes my work and then tells me what a hard time she’s having,” he said. “That means she’ll let me give her some money.” He deposited the letter in the wastebasket. He unfolded his Times and settled his dark-horn-rimmed glasses more firmly on his nose. I turned back to my preparations for class.

His class sessions and occasional readings from his work were interrupted in March by a two-week visit to Greece for the State Department to coincide with a performance of his Requiem for a Nun. His busy schedule was crowned by his reception of the Silver Medal of the Athens Academy. But this triumph came at a cost. The combination of fatigue, celebration, and his pattern of retreat from crowds precipitated a drinking cycle. Leaving behind him a trail of lost objects, he was back in Virginia in early April, in the hospital. Before long, however, he had recuperated enough to resume riding with friends, aiming to condition himself and take jumping instruction for fox hunting with the Keswick and Farmington Hunts.

This was not an activity I had the skill or time to share with him, but fortunately there was another one. For a few years I had been helping to judge places in track meets or take times with a stopwatch, in return for which I received two seasons’ football tickets. With the approval of our supervisor, anatomist James Kindred, Faulkner joined me at the finish line of the 440-yard race. Our job was to pursue the first three finishers to get their names accurately. I should have known better by now than to think my fellow judge could escape observation and blend into the slim crowd in his khaki pants, linen jacket, and old Panama hat. Most of the athletes appeared not to know who this official was who walked after them rapidly at races’ ends asking, “Young man, young man, what’s your name?” One race, however, was different. The mile relay had just been won with a brilliant sprint by the visitors’ anchor man. A moment later, one of the runners walked up to us, his face flushed, and his chest heaving. “Sir,” he gasped, “in our class” – he struggled for breath – “we’ve just been reading your book.” He held out a copy of Light in August. “Would you please autograph it for me?” I recognized the visitors’ anchor man in the relay. Faulkner smiled and signed it. The winner thanked him profusely and walked away with an additional laurel from Charlottesville. As we were jotting down the first set of names, one of the officials who had met him earlier observed our progress.

“Well, Mr. Faulkner,” he said, “I see they’ve put you to work.”

“Yes,” he replied. “Blotner and I are workin’ for our letter. When we get it, we’re goin’ to put it on a sweater. I get to wear it on Sattidays.”

When it came to racing, he preferred the equine variety. He was riding often in spite of near-chronic back pain from injuries old and new and the inconvenience of having to depend occasionally on others for rides out to Grover Vandevender’s farm where he rode. We discussed the problem one morning over coffee in Fred’s office, which had become our Squadron Room. He said he had considered a motor scooter because a cycle might jar his back.

“We ought to get one of those belts for your back,” Fred said.

“Yes,” I added, “one of those wide black leather ones with red and blue stones on it.”

“We could letter ’Charlottesville’ on it,” Fred said.

“No,” Mr. Faulkner said, “we should put on it, ’Department of English.’”

The ambience of his various appearances was unpredictable and sometimes anticlimactic, as at one event of a kind he would have shunned ordinarily. On Friday, April 12, John Dos Passos arrived to address the law school and the Jefferson Society. A large man, smiling and diffident, he talked afterward at a reception with undergraduates clustering around him. Then the circle broke as some of the students made way for this other guest come to congratulate the speaker. When they saw it was Faulkner, those closest fell silent to hear the exchange between the two novelists who – according to Faulkner at least – were among the five best contemporaries in their craft. Faulkner extended his hand, and Dos Passos, a good head and a half taller, grasped it.

“Hello, Dos,” said Faulkner.

“Hello, Bill,” said Dos Passos.

They exchanged casual pleasantries as the circle reformed at a respectful distance and a photographer recorded the meeting. Dos Passos did not give the impression of shyness Faulkner did, but neither was he voluble, and so the two frequently fell silent as they sipped their drinks. After a short but polite interval, Faulkner offered his hand again.

“Well, good night, Dos,” he said.

“Good night, Bill,” his old acquaintance responded genially, and as the ring closed once more, Faulkner set off on foot for home.

For his scheduled public appearances, however, he usually rose to the occasion, and he was anxious to give what he considered full value for his appointment and remained wary of drifting into a formulaic routine of classroom sessions. As the end of April neared, it was time, as he put it, to “put the show on the road.” Students and faculty at other Virginia institutions were anxious to hear him, and so we set off in my car on a beautiful afternoon for Mary Washington College, the university’s sister institution in Fredericksburg an hour away. Well-turned out, his hair white from the morning’s shower, he was in good form, Reading rapidly as usual, from “Spotted Horses,” he held the attention of the young ladies of Mary Washington, who listened in a hush. They asked questions that were intelligent as well as respectful, and as if put on his mettle by their attractive presence, he was witty and responsive.

The American ambassador had recalled to me how after Faulkner discharged his last Nobel Prize obligation, he helped himself liberally from the drink tray as if he were saying, “School’s out.” Now, leaving Mary Washington, we walked through the sombre brick-walled cemetery where Confederate soldiers lay beneath dark weathered stones with fading letters. Any meditations on mortality they inspired may have increased his readiness for relaxation. We stopped by a meadow and uncorked the bottle of Jack Daniel’s he had brought along. It tasted fine out of paper cups with ice and a little water. Talking at random we looked out over the country. We had a second drink. When it was finished Mr. Faulkner said, “Let’s have another one.”

“Why don’t we go on,” Fred countered, “and find a restaurant where we can have one while we’re waiting for dinner?”

“I don’t see why we can’t finish the bottle here,” said Mr. Faulkner, with what sounded to me like the slightest edge to his voice.

Fred and I exchanged fleeting wary glances. We were both bourbon fanciers but essentially moderate drinkers, and I think Fred may have shared my sudden vision of darkness falling on the meadow with none of us in best shape to drive the car. Thinking too of Yvonne and the children at home waiting for dinner, I said “Let’s have one more here and then go.” Fred poured the drinks, and we enjoyed them without further discussion. The Jack Daniel’s was tasting even better now, but we went on to find a restaurant that served moderately good steaks, and at last we returned home in the fragrant evening.

There were further occasions for relaxation that spring. Each of us on the Balch Committee and our wives had found occasions to invite the Faulkners for drinks. If William Faulkner tended to be withdrawn, his wife, Estelle, had always been outgoing and popular, so much so that Faulkner’s college friend and first literary agent, Ben Wasson, would recall her in her youth as “the Butterfly of the Delta.” Slim now almost to the point of emaciation, she dressed elegantly. She had long since mastered the traditional arts of the Southern belle. Graceful and animated, never at a loss for conversation, she charmed effortlessly. “Call me ’Stelle,’” she had said and made us feel perfectly natural when we did.

The Town, the second volume of the projected trilogy describing Faulkner’s fictional Snopes family, made its appearance, and he gave us our inscribed copies. In the warm sunlight of late May, he and Estelle entertained the whole English Department, the French doors of their graceful Georgian home on Rugby Road thrown open to the spacious flagstone terrace. By mid-June, with the last of his University obligations discharged, we were free to go on the first of several planned expeditions. One bright morning at 5:30 his gray Plymouth station wagon pulled up in front of our house, and I went out to join him, Paul Summers, and Estelle’s son, Malcolm Franklin, for a tour of the Seven Days’ battlefields, the scene of bloody Civil War fighting. We took turns driving, and then, as the day wore on, made our way from Malvern Hill to Petersburg and Amelia Courthouse. Paul had brought along one of his West Point textbooks, and we stopped frequently to orient ourselves. It became obvious that Mr. Faulkner knew the battles in considerable detail, far better than any of the rest of us. The day turned warm and sunny, and though we were solemn and inclined to silence in the midst of the stone testimonials to awful carnage there, the trip had been a memorable one.

That evening, the Faulkners gave a Squadron dinner on the terrace at Rugby Road. (We were acquiring our own memorabilia even though we had thus far obtained only a model of the RAF Sopwith Camel for him – the Chief – and not yet the TBF bomber for Fred or the Flying Fortress for me.) We savored Estelle’s giant shrimp curry, ate quail eggs, and drank champagne. After dessert we had coffee and brandy in the candle light. In a momentary pause in the conversation, the Chief spoke. “Lieutenants Gwynn and Blotner, front and center,” he said in an abrupt, clipped voice.

Fred and I rose, stepped forward together, and came to attention. He stood at attention too and made a short rapid speech about our work, then stopped as abruptly as he had begun. The surprise still lingering, we said “Thank you, sir,” saluted, performed an uncoordinated about-face, and resumed our places. Fred was then 41, six years my senior, but I think he must have felt a glow just as I did. By late June the Faulkners were gone, back home in Mississippi attending to Rowan Oak and the needs of his Greenfield Farm out in the country. Indoor as well as outdoor work kept him busy, and it would be five months before he and Estelle could return to Charlottesville.

When the Faulkners returned, they brought with them two paintings by his mother, Maud Falkner – now increasingly well known for her realistic "American Primitive" style – one for the Gwynns and one for us. Although the Chief rode and hunted and sailed his sloop at home, he found more diversion here in Virginia. As he had gone to Little League baseball games with me in the spring, now in November he was ready to sample University of Virginia football. “I like this,” he told me. “This is real amateur sport. At home they got a tame millionaire and he buys a team for them.” Before half-time began the producer of the game’s radio coverage asked me if I could persuade Mr. Faulkner to talk with “Bullet Bill” Dudley, a Virginia football “immortal,” who was doing the color portion of the broadcast. When he agreed and followed me up the crowded aisle, the effluvium of his farm trench coat was nearly overpowering as we entered the confines of the broadcast booth. Reading from the producer’s scrawled note, Bullet Bill declared, “it’s a real pleasure to have with us today Mr. William Faulkner, winner of the Mobile Prize for Literature.” The Laureate was increasingly a unique presence in Charlottesville.

In the spring he had begun talking about moving to Charlottesville permanently. He had broached the subject sitting in my office. “I was thinking that it might be good to have some connection with the university after I’m through being writer-in-residence – if they can still use me, that is.” Mr. Stovall and Fred and I determined that we would go to the administration again when he returned in February. It was not as if he did not have work of his own to do. He was now well into The Mansion, the volume that would complete the Snopes trilogy begun so long ago. In January he remained faithful to a schedule of office hours that saw him seated at his Cabell Hall desk from 10:30 until noon five days a week. When he had no callers, he would read his New York Times for a while, then take from his trench coat a thick roll of white copy paper. Soon anyone passing could hear his slow tapping on Floyd Stovall’s portable typewriter.

Fred and I had only gradually become accustomed to our unique situation. In our developing careers we had gradually come to teach American classics, the work of Hawthorne and Melville, Twain and James, and others in the canon. Then suddenly we had found ourselves teaching that of an artist whom many anthologists and literary historians were placing on a similar level. It was a heady experience, in part because, though he was far from voluble himself, he gave us leave to ask anything in the class sessions and obviously made an effort to answer conscientiously. Our unspoken part of the bargain was to respect his personal and professional privacy. When we talked as friends in the Squadron Room, we did not interpolate the kind of literary questions he had heard for years, and in class we had asked more than we had ever expected to do. One result was his unasked volunteering of information virtually fresh from his worktable. Greeting him one morning, I asked how he was feeling. Not only was he fine, he said, but “I even got back to work on my novel.” Another morning in mid-February found him even more ready to talk.

“Get any work done this morning?” Fred asked.

“Yes,” he replied, stirring his coffee. “I haven’t worked for so long that it’s fun again. I got back to that Memphis whorehouse in Sanctuary, Miss Reba’s. That’s where I am right now. Senator Snopes is in Memphis and the nephew is going to barber college and they’re trying to preserve his innocence.” This was the kind of story-telling he had done as a young aspirant in Greenwich Village, sitting shoeless on the floor among friends, his imagination still busy with his creations. When Fred asked if Eula Varner’s daughter had reappeared, he volunteered more. “No,” he said, “that’s the third-act curtain to the whole thing” and went on to describe the action on which the end of the plot turned.

It was exciting to be this close to the artist’s smithy, and he even gave us a sense of participation in some of his work. In February he wrote out a talk he had been invited to deliver to three societies on the Grounds of the University. The political atmosphere in Virginia provided a special element of drama. The governor had promulgated a doctrine of “massive resistance” to federal pressure for integration. It would have been politic for William Faulkner to avoid the subject, but when he brought his talk with him to Fred’s office at coffee time and asked us both to read it, we saw that he had instead met the issue head on. “A Word to Virginians” was an appeal to lead the whole South in educating the Negro. The other Southern states still looked to Virginia as a mother. They had ignored her counsel once before, to their grief, but now, he wrote, “Show us the way and lead us in it. I believe we will follow you.”

“How’s that?” he asked us. We had both read the pages quickly.

“Good,” I said, thrilled more, I believe, by his request that we read his work than by the carefully worded appeal itself.

A week before, Floyd Stovall had talked to President Darden about some permanent tie to the university for Mr. Faulkner. Darden responded that though he appreciated Faulkner’s contribution, he felt that other writers who came under the Balch program would feel that they too might achieve permanent connections with the university. Though this seemed a lame and transparent excuse to us, we felt that Faulkner’s speech must have convinced Darden that his position was right. And the closing of some public schools, extending through 1958-1959 showed that it had extensive support.

Though there were still nearly a dozen class appearances ahead before William Faulkner’s term as writer-in-residence was over, there was a sense for us of the end of things as spring came in. We still gathered for coffee each morning, the Chief sitting in the low camp chair Fred had stencilled “Balch Chair of American Literature.” Katherine Anne Porter had been chosen as the next writer-in-residence. “I guess we ought to get a pipe,” I said “and have it engraved ‘Emily Clark Balch Pipe of American Literaure.’ That would still be yours.” He chuckled soundlessly. If we needed evidence that some did not share our regret at his vacating the position, I had heard it a few days earlier from another member of the Balch Committee, Fredson Bowers, who seemed likely to succeed Floyd Stovall as department chairman.

“Did ‘Pappy’ get over the idea that he was going to be the permanent writer-in-residence?” he asked me, with a broad grin. I replied that he had never seriously entertained that idea, and more than once he had asked me to tell him if he stopped being effective in the job.

Sometimes now his remarks would take on a valedictory tone, and we began a round of Squadron dinners, for in late May the Faulkners would return to Mississippi for the summer. Not long after that the Gwynns would be leaving as Fred took up the chair of the English department at Trinity College in Connecticut. Then, in August my wife and I would be departing for a Fulbright Lectureship at the University of Copenhagen. But these dinners were festive occasions. Knowing Mr. Faulkner’s taste for French cuisine, Yvonne served beef bourguignon, with baba au rhum for dessert. As he put down his spoon he asked, “What time’s breakfast, Miss Yvonne?”

He fulfilled his last public sessions and continued work at home on The Mansion. Earlier he had told Fred and me that he wanted us to see his new book. Because I had thought this just a polite remark, I was totally surprised when he arrived at our door one afternoon and handed me a manila portfolio.

“Here,” he said brusquely, “you can read this.” A glance inside showed me that it was a ribbon typescript, not just a carbon copy. It was the first third of his new novel, he said.

“You have another copy at home, don’t you?” I asked anxiously.

“No,” he said abruptly.

After he had left, I showed Yvonne what he had given me. She was aghast. “You don’t mean you expect to keep that overnight in a house with three little girls with crayons?” I read it that night, put it on top of our highest bookcase, and returned it to him the next day at cocktail time.

Even though the time was short, Floyd Stovall decided on one more try and walked up the Lawn to the president’s pavilion. “Mr. Darden,” he said, “I’d like to propose, with the concurrence of the English Department, that Mr. Faulkner be made an honorary lecturer in American literature to keep up his connection with the university.”

“There are no honorary positions at the University of Virginia,” was the reply. Colgate W. Darden had kept his no-hitter going.

There were, however, some tangible mementos. One night as the Faulkners sat in their Rugby Road living room, there was a knock on the door. Faulkner opened it and found no one there, but on the steps was a large package containing a silver tray from the Seven Society, an anonymous group of the university’s most distinguished sons. It was engraved to him in tribute to his contribution to the life of the university.

Our Fulbright year of 1958-59 passed rapidly with my teaching at the University of Copenhagen, lecturing elsewhere, and traveling strenuously in the summer through the Alps and as far as Rome before our return to Charlottesville in August. The Faulkners were back as the gold of October gave way to dappled November. Back in time for the Blessing of the Hounds, he was riding now with not just one hunt but with two, togged out in derby, stock and shining boots. But he was not neglecting his vocation for his avocation. He had finished his work on The Mansion, and on November 13 of 1959 it was published. Reading something he had written recently, I never knew when I would experience the shock of recognition. Sitting in Fred Gwynn’s office during those coffee and hangar-flying sessions, we had told war stories. Fred had said little about flying a TBF off a carrier in the Pacific, but I had told about the end of my brief career as a bombardier until we were shot down over Cologne, and about watching helplessly as green target flares drifted right over Stalag Luft XIII D when the RAF came over to bomb one of Germany’s largest marshalling yards. When I read Chapter Thirteen of The Mansion, I sat straight up in my chair. “I enjoyed that part about Chick’s experience in Germany,” I told the author later.

“I used your story about being bombed in POW camp,” he said with a smile. “I lifted that right from what you told me.”

There were other items that drew on our experiences. Fred and I had edited the Chief’s class conferences, and 36 of them would be published that year as Faulkner in the University. Saxe Commins at Random House had opposed the project for fear it would be thought Faulkner’s last word on his work. But then it was agreed that the University Press of Virginia would publish it, with the royalties to be split evenly among the three of us. We also made the joint resolve that they would always be spent on Jack Daniel’s.

Faulkner’s Virginia connection was signalized in two other ways as well. Linton Massey had suggested to University Librarian John C. Wyllie that some connection be found for Faulkner. Wyllie cautiously agreed, and in early January he released the news that William Faulkner would become consultant on contemporary literature to the Alderman Library. Very shortly thereafter he had a call from President Darden asking where he got the authority to add people to his staff and payroll that way. Tough-minded John Wyllie had a ready response. “There’s no money involved at all.” Faulkner would have a study with a desk, a chair, and a typewriter. “He’ll have access to anything in the library, but nobody will have access to him.” This time Darden made no rejoinder.

Buying land was a different kind of commitment. Hedda Hopper had reported from Hollywood that Rowan Oak was for sale, with a room reserved for Faulkner’s permanent use. Three days later the Associated Press followed this fanciful account with the word that the Faulkners had bought a home on Rugby Road in Charlotttesville and would move into their handsome Georgian brick house in August. He might never be able bring himself to sell Rowan Oak, but he intended to spend as much time living in Virginia as his tax situation would permit.

They settled in comfortably there, but he had his eye on a place in Albemarle County where he could leave his own home, mount Stonewall or Fenceman, and ride to Grover Vandevender’s farm to set out with him for the hunt. After searching in the winter and spring, he settled on the place. “I want Red Acres,” he wrote his friend, Linton Massey, asking if he would let him have $50,000 on demand if he needed it to seal the deal. Faithful as ever, he agreed. It looked as if Red Acres would be his, with its nine-box-stall, stable and groom’s room, and seven other buildings. The residence itself was a handsome brick structure with a central portion nearly a century old. To look from the wide front veranda was to see for miles, the panorama of rolling hills and meadows like an 18th-century landscape. Almost within his grasp, it eluded him when he died of a heart attack in Oxford, Mississippi, on July 7, 1962.

A year later I began my biography of William Faulkner. Two years later Yvonne and I bought 917 Rugby Road from Estelle Faulkner and I continued my work there.

©2001, 2005 Joseph Blotner

Below: Photo by unidentified photographer from Faulkner Papers Photograph Collection [Print# 0066; Digitization# 000005731_0003]. Caption on back: "Faulkner jumping 'Powerhouse' at Grover Van Devender's point-to-point Buck Mountain Riding Club, Spring Show, May 15, 1960."

Below: Photo by George Barkley of William Faulkner with hunting horn, at Farmington Hunt Club, 1960.

Below: Photo by George Barkley of Faulkner riding with Grover Van Devender (red coat) and unidentified man, at Farmington Hunt Club, 1960.

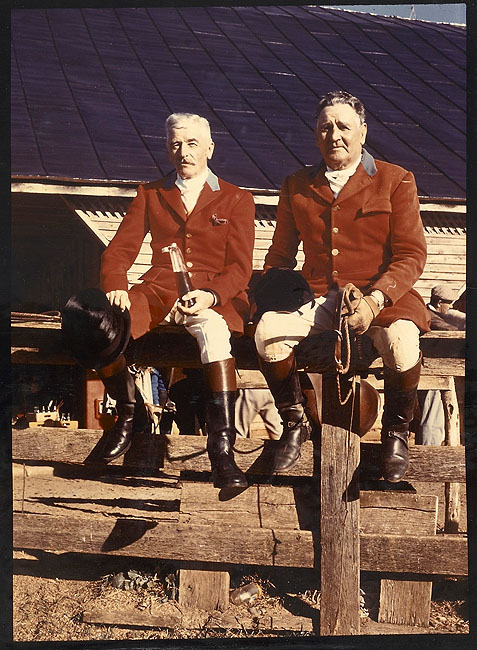

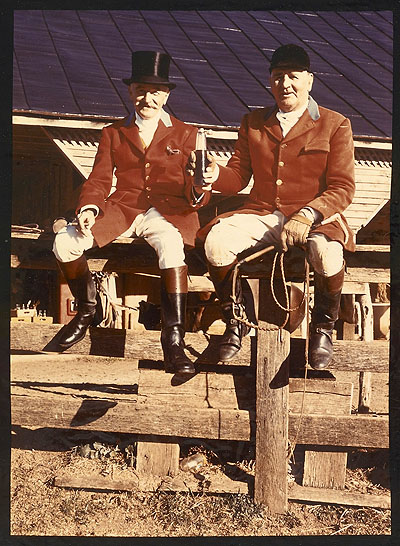

Below: Photo by George Barkley from Faulkner Papers Photograph Collection [Print# 0070; Digitization# 000005731_0011]. Caption on back: "Faulkner with Grover Van Devender, M. F. H., Farmington Hunt Club, taken at Van Devender's 1960, Autumn." The object Faulkner holds is a flask.

Below: Photo by George Barkley from Faulkner Papers Photograph Collection [Print# 0069; Digitization# 000005731_0009]. Caption on back: "Charlottesville, VA. With Grover Van Devender, Huntsman, Farmington Hunt Club, at Van Devender's, 1960, Autumn." The two men are holding a flask.

Below: Photo by George Barkley from Faulkner Papers Photograph Collection [Print# 0068; Digitization# 000005731_0007]. The caption on the back reads: "W.F., Mrs. Daniel Wells, Grover Van Devender, [Betty] Barkley at Grover Van Devender's, 1960." But the woman on the far right is actually Mary Farr Jordan.

Below: Photo by George Barkley from Faulkner Papers Photograph Collection [Print# 0071; Digitization# 000005731_0013]. Caption on back: "Faulkner and Van Devender, M. F. H. Farmington Hunt Club, 1960."

Below: Photo by George Barkley from Faulkner Papers Photograph Collection [Print# 0062; Digitization# 000005731_0001]. The caption on back of the photo reads: "Left to Right Betty Barkley, W.F., Molly Nicol, [unidentified], Doug Nicol, Grover Van Devender, Katinka Hume, Paul Bloch (MFH), identified Connie Massey, at Farmington Hunt Club, photo by George Barkley." The woman on Faulkner's right, however, is actually Mary Farr Jordan.

Below: Photo by George Barkley from Faulkner Papers Photograph Collection [Print# 0067; Digitization# 000005731_0005]. Caption on back: "W.F. - Van Devender, M. F. H. Farmington Hunt Club, 1960."