The Virginia Spectator Writer in Residence Issue (April 1957, vol. 118, no. 7, pp. 10-11, 28)

The Personality of William Faulkner

By William J. Powell

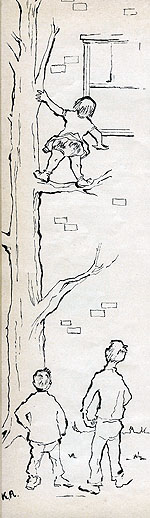

The picture to the left is

worth a thousand words in trying to discover the personality of William Faulkner. The picture is a mental image that came to him of

children who were sent out in the yard to play during their grandmother's funeral. Only one of the little girls was big enough of

spirit to climb a tree to look in the window to see what was going on. But along with her courage, she had muddy pants. This mental

image struck Faulkner where he lives, for it was the beginning of many years of struggle during which he labored to convert the

essence of this mental scene, which was an intuitive experience, to words on paper. He tried a short story first, then a book, The

Sound and the Fury, attacking it from almost every conceivable angle and never being satisfied that he had put the epiphany

of the mental scene down on paper even after adding a preface entitled "Appendix."

The picture to the left is

worth a thousand words in trying to discover the personality of William Faulkner. The picture is a mental image that came to him of

children who were sent out in the yard to play during their grandmother's funeral. Only one of the little girls was big enough of

spirit to climb a tree to look in the window to see what was going on. But along with her courage, she had muddy pants. This mental

image struck Faulkner where he lives, for it was the beginning of many years of struggle during which he labored to convert the

essence of this mental scene, which was an intuitive experience, to words on paper. He tried a short story first, then a book, The

Sound and the Fury, attacking it from almost every conceivable angle and never being satisfied that he had put the epiphany

of the mental scene down on paper even after adding a preface entitled "Appendix."

That he would have difficulty in the task is not astounding, because he considered the whatness of that picture a keystone of the universe without which the universe would collapse. The measure of greatness of any writer is the degree to which he sees the universe in any image or event, for indeed the universe would collapse if even its smallest part were removed. Faulkner senses the truth in this, and hence he is able to find importance and significance in a great many things, and this provides him with a sense of values which far transcends the values of average society and gives a radiance to a pair of muddy pants whose wearer has hoisted them above the heads of her contemporaries. He is able to find nobility in a prostitute and prostitution in nobility.

Because William Faulkner sees the greater value in the recognition that each person's values are valid for all people collectively, he has a great respect for writers who attempt to put the universe "on the head of a pin" in their books, writers whose characters "don't just move from page one to page 320 of one book, but between whom there is continuity like a blood-stream which flows from page one through to page 20,000 of one book. The same blood, muscle and tissue binds the characters together." It was on this basis that Faulkner rated Thomas Wolfe above himself, himself second, Dos Passos third, Caldwell fourth, and Hemingway fifth. He rated them on how much of the universe each tried to put on the head of the pin which was their total writing.

Paradoxically, Faulkner feels that to be great, a writer must necessarily be a failure by virtue of having tried to do more than he was capable of doing. The higher the aim of the writer, the more glorious will be the failure, and the more glorious his failure, the more successful and great will be the writer, assuming that the writer tries his hardest to achieve his aim.

Implicit in this seemingly contradictory formula, however, is the assumption that the writer understands, in the unwritten and unwritable language of his soul, as much of the universe as he attempts to put in writing. What he must understand is not the word "universe," but the universe itself. Since the degree to which the universe is understood by a person is the same degree to which he has overcome prejudices of all varieties, it seems that Faulkner's test could be more simply stated : That the more prejudice that a writer overcomes, the greater his writing will be. This is essentially the personality of Faulkner : He has little prejudice.

For those who are interested, William Faulkner's hobbies are flying (a former member of the Canadian Flying Corps), supervising operations on his farm, hunting, guns, and dogs. He is said to have a courtly manner, addressing all males as "sir" and all females as either "ma'am," "wellum," "yessum," or "nome." He is usually dressed in flannels or tweeds from his taylor on Savile Row, London, wears a tyrol hat of brown color without goat whisker, smokes a pipe, has a blazer with an R.A.F. emblem on the pocket. He does not offer to go into things, but is receptive usually, when things come to him. He is known to be courteous and well mannered. He has a sense of humor which is sometimes misunderstood, but such misunderstandings do not perturb him as a rule. An example of this was the statement he made at a press conference in answer to the question, "Why did you accept the invitation of the Department of English to be a writer in residence at the University of Virginia?" Faulkner answered, "It was because I like your country. I like Virginia, and I like Virginians, because Virginians are snobs. A snob has to spend so much time being a snob that he has little left to meddle with you, and so it's pleasant here." Those who resented this statement were either snobs or people who did not realize that the press conference was relaxed, humorous, and even whimsical in tone. But all of these things are merely the garments of Faulkner's personality, however, and are analogous to the word "universe," as opposed to the universe itself. William Faulkner gives the impression of honesty and sincerity with himself as well as others, and has a dignity about him in spite of the occasional showing of muddy pants.

©1957 The University of Virginia

The Virginia Spectator Writer in Residence Issue (April 1957, vol. 118, no. 7, pp. 10-11, 28)

The Personality of William Faulkner

By William J. Powell

The picture to the left is

worth a thousand words in trying to discover the personality of William Faulkner. The picture is a mental image that came to him of

children who were sent out in the yard to play during their grandmother's funeral. Only one of the little girls was big enough of

spirit to climb a tree to look in the window to see what was going on. But along with her courage, she had muddy pants. This mental

image struck Faulkner where he lives, for it was the beginning of many years of struggle during which he labored to convert the

essence of this mental scene, which was an intuitive experience, to words on paper. He tried a short story first, then a book, The

Sound and the Fury, attacking it from almost every conceivable angle and never being satisfied that he had put the epiphany

of the mental scene down on paper even after adding a preface entitled "Appendix."

The picture to the left is

worth a thousand words in trying to discover the personality of William Faulkner. The picture is a mental image that came to him of

children who were sent out in the yard to play during their grandmother's funeral. Only one of the little girls was big enough of

spirit to climb a tree to look in the window to see what was going on. But along with her courage, she had muddy pants. This mental

image struck Faulkner where he lives, for it was the beginning of many years of struggle during which he labored to convert the

essence of this mental scene, which was an intuitive experience, to words on paper. He tried a short story first, then a book, The

Sound and the Fury, attacking it from almost every conceivable angle and never being satisfied that he had put the epiphany

of the mental scene down on paper even after adding a preface entitled "Appendix."

That he would have difficulty in the task is not astounding, because he considered the whatness of that picture a keystone of the universe without which the universe would collapse. The measure of greatness of any writer is the degree to which he sees the universe in any image or event, for indeed the universe would collapse if even its smallest part were removed. Faulkner senses the truth in this, and hence he is able to find importance and significance in a great many things, and this provides him with a sense of values which far transcends the values of average society and gives a radiance to a pair of muddy pants whose wearer has hoisted them above the heads of her contemporaries. He is able to find nobility in a prostitute and prostitution in nobility.

Because William Faulkner sees the greater value in the recognition that each person's values are valid for all people collectively, he has a great respect for writers who attempt to put the universe "on the head of a pin" in their books, writers whose characters "don't just move from page one to page 320 of one book, but between whom there is continuity" like a blood-stream which flows from page one through to page 20,000 of one book. The same blood, muscle and tissue binds the characters together." It was on this basis that Faulkner rated Thomas Wolfe above himself, himself second, Dos Passos third, Caldwell fourth, and Hemingway fifth. He rated them on how much of the universe each tried to put on the head of the pin which was their total writing.

Paradoxically, Faulkner feels that to be great, a writer must necessarily be a failure by virtue of having tried to do more than he was capable of doing. The higher the aim of the writer, the more glorious will be the failure, and the more glorious his failure, the more successful and great will be the writer, assuming that the writer tries his hardest to achieve his aim.

Implicit in this seemingly contradictory formula, however, is the assumption that the writer understands, in the unwritten and unwritable language of his soul, as much of the universe as he attempts to put in writing. What he must understand is not the word "universe," but the universe itself. Since the degree to which the universe is understood by a person is the same degree to which he has overcome prejudices of all varieties, it seems that Faulkner's test could be more simply stated: That the more prejudice that a writer overcomes, the greater his writing will be. This is essentially the personality of Faulkner: He has little prejudice.

For those who are interested, William Faulkner's hobbies are flying (a former member of the Canadian Flying Corps), supervising operations on his farm, hunting, guns, and dogs. He is said to have a courtly manner, addressing all males as "sir" and all females as either "ma'am," "wellum," "yessum," or "nome." He is usually dressed in flannels or tweeds from his taylor on Savile Row, London, wears a tyrol hat of brown color without goat whisker, smokes a pipe, has a blazer with an R.A.F. emblem on the pocket. He does not offer to go into things, but is receptive usually, when things come to him. He is known to be courteous and well mannered. He has a sense of humor which is sometimes misunderstood, but such misunderstandings do not perturb him as a rule. An example of this was the statement he made at a press conference in answer to the question, "Why did you accept the invitation of the Department of English to be a writer in residence at the University of Virginia?" Faulkner answered, "It was because I like your country. I like Virginia, and I like Virginians, because Virginians are snobs. A snob has to spend so much time being a snob that he has little left to meddle with you, and so it's pleasant here." Those who resented this statement were either snobs or people who did not realize that the press conference was relaxed, humorous, and even whimsical in tone. But all of these things are merely the garments of Faulkner's personality, however, and are analogous to the word "universe," as opposed to the universe itself. William Faulkner gives the impression of honesty and sincerity with himself as well as others, and has a dignity about him in spite of the occasional showing of muddy pants.

©1957 The University of Virginia