Introduction and Contexts

- Faulkner At Virginia: Introduction

- Faulkner in the Late 1950s

- The US in the Late 1950s

- Virginia in the Late 1950s

Faulkner at Virginia: An Introduction

In December, 1957, getting ready to begin his second Spring semester at the University of Virginia, Faulkner joked in a letter that he was "just the writer-in-residence, not the speaker-in-residence."

He certainly wrote while he was here, including much of The Mansion, but did more than enough speaking to earn that

second title. Between February and June, 1957, and February and May, 1958, at thirty-six different public events, he gave two

addresses, read a dozen times from eight of his works, and answered over 1400 questions from audiences made up of various groups,

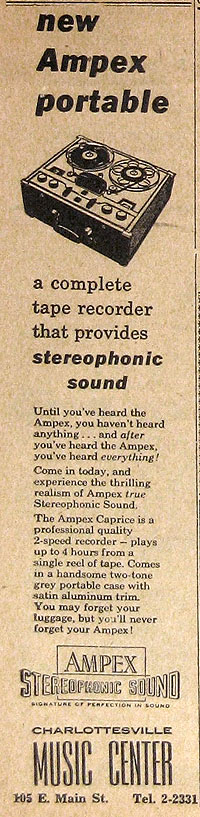

ranging from UVA students and faculty to interested local citizens. Most of those sessions were recorded on the advanced

technology of that time – the reel-to-reel tape recorder. In this archive you can hear 1690 minutes (over 28 hours) of

those recordings.

In December, 1957, getting ready to begin his second Spring semester at the University of Virginia, Faulkner joked in a letter that he was "just the writer-in-residence, not the speaker-in-residence."

He certainly wrote while he was here, including much of The Mansion, but did more than enough speaking to earn that

second title. Between February and June, 1957, and February and May, 1958, at thirty-six different public events, he gave two

addresses, read a dozen times from eight of his works, and answered over 1400 questions from audiences made up of various groups,

ranging from UVA students and faculty to interested local citizens. Most of those sessions were recorded on the advanced

technology of that time – the reel-to-reel tape recorder. In this archive you can hear 1690 minutes (over 28 hours) of

those recordings.

The Writer in Residence

There’s no need for me to say much about Faulkner's tenure as the first Balch Writer-in-Residence. As you scroll

down this page, you’ll find several ways to explore it for yourself. Chronologically, these begin with 31 articles

reprinted from the UVA and Charlottesville newspapers from October 1956, when his appointment was announced, through the end of

the Spring term, 1958. On 6 July 1962, the day Faulkner died, the English department held a press conference at which, even as his

loss was mourned, his earlier presence on the Grounds (as UVA calls its campus) was remembered and discussed; you can listen to

those comments. In 2001 Joseph Blotner, who along with Frederick Gwynn was largely responsible for inviting the novelist here and

his almost constant companion during his public appearances, wrote a rich account of that experience that you can read. Blotner's

essay on “Mr. Faulkner” is followed by the recollections of eleven people who were UVA students or teachers during the period

of Faulkner's residency. You can even listen to what Faulkner himself told audiences about the experience at the end of both his

first term

There’s no need for me to say much about Faulkner's tenure as the first Balch Writer-in-Residence. As you scroll

down this page, you’ll find several ways to explore it for yourself. Chronologically, these begin with 31 articles

reprinted from the UVA and Charlottesville newspapers from October 1956, when his appointment was announced, through the end of

the Spring term, 1958. On 6 July 1962, the day Faulkner died, the English department held a press conference at which, even as his

loss was mourned, his earlier presence on the Grounds (as UVA calls its campus) was remembered and discussed; you can listen to

those comments. In 2001 Joseph Blotner, who along with Frederick Gwynn was largely responsible for inviting the novelist here and

his almost constant companion during his public appearances, wrote a rich account of that experience that you can read. Blotner's

essay on “Mr. Faulkner” is followed by the recollections of eleven people who were UVA students or teachers during the period

of Faulkner's residency. You can even listen to what Faulkner himself told audiences about the experience at the end of both his

first term

and his second one

and his second one

. These accounts don’t always agree – but readers of Faulkner are used to that.

. These accounts don’t always agree – but readers of Faulkner are used to that.

At the same time, it's important to point out that what Faulkner says on these tapes doesn't always agree with what he said

in the past – or with what biographers and scholars have learned about the facts of his life and career. One way to

think about what you'll hear is as Faulkner performing Faulkner, presenting the version of himself and his work that he

may already, at age sixty, have been thinking of as a legacy. As he himself notes almost a dozen different ways on these tapes,

writers are “congenital liars”

At the same time, it's important to point out that what Faulkner says on these tapes doesn't always agree with what he said

in the past – or with what biographers and scholars have learned about the facts of his life and career. One way to

think about what you'll hear is as Faulkner performing Faulkner, presenting the version of himself and his work that he

may already, at age sixty, have been thinking of as a legacy. As he himself notes almost a dozen different ways on these tapes,

writers are “congenital liars”

. After listening several times to the recordings, however, I'd also say that there is nothing insincere about his desire at

this point in his career to reach the people in his audiences. Throughout his time at UVA, he was extremely generous in meeting

the demands of his occasions as Writer-in-Residence. He invites audiences to ask him any kind of question

. After listening several times to the recordings, however, I'd also say that there is nothing insincere about his desire at

this point in his career to reach the people in his audiences. Throughout his time at UVA, he was extremely generous in meeting

the demands of his occasions as Writer-in-Residence. He invites audiences to ask him any kind of question

. He was often asked about the same thing more than once; you’ll hear, for example, how formulaic are the responses

he worked out to questions about “how he became a writer” or “how he came to write

Sanctuary,” but to me even at those moments Faulkner seems anxious to connect with his listeners. He is even

more frequently asked questions he doesn’t want to answer, about for example exactly what he meant by a certain symbol

in a particular story

. He was often asked about the same thing more than once; you’ll hear, for example, how formulaic are the responses

he worked out to questions about “how he became a writer” or “how he came to write

Sanctuary,” but to me even at those moments Faulkner seems anxious to connect with his listeners. He is even

more frequently asked questions he doesn’t want to answer, about for example exactly what he meant by a certain symbol

in a particular story

. To such kinds of questions his answers are often evasive as well as formulaic, but they are never impatient. As a novelist

he often makes great demands on his reader. On these tapes, however, you won’t hear a High Modernist cloaking himself in

“silence, exile and cunning,”

*

but a serious artist trying to make himself and his work as approachable as possible.

. To such kinds of questions his answers are often evasive as well as formulaic, but they are never impatient. As a novelist

he often makes great demands on his reader. On these tapes, however, you won’t hear a High Modernist cloaking himself in

“silence, exile and cunning,”

*

but a serious artist trying to make himself and his work as approachable as possible.

Although he liked to say that the only books an author never needs to look at again are the ones he wrote himself

Although he liked to say that the only books an author never needs to look at again are the ones he wrote himself

, he decided to re-read Absalom, Absalom! before beginning his second term as Writer-in-Residence, so that he could

answer questions about that book more helpfully.

*

While he apologizes – rightly, listeners are likely to feel – for his shortcomings as a reader of his own

work, when he visited classrooms he was clearly willing to read whatever fitted the pedagogic needs of a particular instructor. As

for the texts he himself chose to read, he shows a decided preference for “Faulkner lite,” for humorous rather

than serious selections. But he was not afraid to challenge his UVA audience, as became clear when he decided to commence his

second Spring semester in “Residence” by delivering “A Word to Virginians,” a nine-minute

speech urging them to help solve rather than exacerbate the growing crisis over court-ordered integration in the Jim Crow South.

To 21st century listeners, his exhortations may sound more like temporizings, but at the time they were controversial, and to some

in his immediate audience, as you can hear for yourself, unacceptable. (The Virginia Faulkner was addressing had already decided on a strategy

of “Massive Resistance” to court-ordered integration, which resulted, later in 1958, in two Charlottesville public schools being closed for five

months to prevent twelve black students from entering them.)

, he decided to re-read Absalom, Absalom! before beginning his second term as Writer-in-Residence, so that he could

answer questions about that book more helpfully.

*

While he apologizes – rightly, listeners are likely to feel – for his shortcomings as a reader of his own

work, when he visited classrooms he was clearly willing to read whatever fitted the pedagogic needs of a particular instructor. As

for the texts he himself chose to read, he shows a decided preference for “Faulkner lite,” for humorous rather

than serious selections. But he was not afraid to challenge his UVA audience, as became clear when he decided to commence his

second Spring semester in “Residence” by delivering “A Word to Virginians,” a nine-minute

speech urging them to help solve rather than exacerbate the growing crisis over court-ordered integration in the Jim Crow South.

To 21st century listeners, his exhortations may sound more like temporizings, but at the time they were controversial, and to some

in his immediate audience, as you can hear for yourself, unacceptable. (The Virginia Faulkner was addressing had already decided on a strategy

of “Massive Resistance” to court-ordered integration, which resulted, later in 1958, in two Charlottesville public schools being closed for five

months to prevent twelve black students from entering them.)

The Recordings

We owe the existence of these tapes to Frederick Gwynn and Joseph Blotner, the members of UVA's English department who were

most involved with Faulkner's residency. It was their idea to record the sessions, and after getting the author’s

consent, it was almost always one or the other of them who ran the tape recorder they carried around to the events. You'll hear

their voices often on the tapes; whenever the students in the room seem to have run out of questions, for instance, one of them

will usually break the silence by asking “Mr. Faulkner” about one of his works. In 1959 they published

Faulkner in the University, edited transcriptions of 36 “class conferences,” as they called the

meetings Faulkner held with various audiences. There are major differences between their book and this archive. Three of the

book’s “conferences” aren’t here. One of these, a classroom session on 20 February 1957,

was not recorded; the brief transcript of it that they print was, they say, “reconstructed from memory.”

According to their Introduction, the tape of another classroom session, on 6 May 1957, was lost after being transcribed. The tape

(or tapes) of Faulkner’s press conference on the first day of his residency, 15 February 1957, is simply missing from

the set of tapes in UVA’s Special Collections, as is the first tape of his 16 May 1957 session with the audience

identified as “Law School Wives”; for Faulkner's remarks on these occasions, users must turn to Faulkner

in the University.

*

Unfortunately these missing tapes contained a lot that I wish we could hear, including much of what Faulkner told UVA

audiences about As I Lay Dying. (As I Lay Dying was also scheduled to be the focus of a 19 May 1957 class

session announced in UVA student newspaper, The Cavalier Daily, but no tapes

of this exist, nor do Gwynn and Blotner mention it, so this session may never have happened.)

We owe the existence of these tapes to Frederick Gwynn and Joseph Blotner, the members of UVA's English department who were

most involved with Faulkner's residency. It was their idea to record the sessions, and after getting the author’s

consent, it was almost always one or the other of them who ran the tape recorder they carried around to the events. You'll hear

their voices often on the tapes; whenever the students in the room seem to have run out of questions, for instance, one of them

will usually break the silence by asking “Mr. Faulkner” about one of his works. In 1959 they published

Faulkner in the University, edited transcriptions of 36 “class conferences,” as they called the

meetings Faulkner held with various audiences. There are major differences between their book and this archive. Three of the

book’s “conferences” aren’t here. One of these, a classroom session on 20 February 1957,

was not recorded; the brief transcript of it that they print was, they say, “reconstructed from memory.”

According to their Introduction, the tape of another classroom session, on 6 May 1957, was lost after being transcribed. The tape

(or tapes) of Faulkner’s press conference on the first day of his residency, 15 February 1957, is simply missing from

the set of tapes in UVA’s Special Collections, as is the first tape of his 16 May 1957 session with the audience

identified as “Law School Wives”; for Faulkner's remarks on these occasions, users must turn to Faulkner

in the University.

*

Unfortunately these missing tapes contained a lot that I wish we could hear, including much of what Faulkner told UVA

audiences about As I Lay Dying. (As I Lay Dying was also scheduled to be the focus of a 19 May 1957 class

session announced in UVA student newspaper, The Cavalier Daily, but no tapes

of this exist, nor do Gwynn and Blotner mention it, so this session may never have happened.)

On the other hand, this archive's complete recordings of the other 32½ sessions contain almost 700 questions and

answers that weren’t published in Faulkner in the University. In general, the choices Gwynn and Blotner made

about what to print hold up well; users familiar with their book probably won’t find many revealing new ideas among the

passages that are being published here for the first time – though Faulkner's thoughts on his works, on writing and

other writers, or on social issues gain new meanings when they are re-connected with the way he spoke them

On the other hand, this archive's complete recordings of the other 32½ sessions contain almost 700 questions and

answers that weren’t published in Faulkner in the University. In general, the choices Gwynn and Blotner made

about what to print hold up well; users familiar with their book probably won’t find many revealing new ideas among the

passages that are being published here for the first time – though Faulkner's thoughts on his works, on writing and

other writers, or on social issues gain new meanings when they are re-connected with the way he spoke them

. In others ways, too, being able to overhear the sessions enriches the story they tell. For example, Faulkner in the

University makes no attempt to represent the reactions of Faulkner's audiences, although those often provide us with

illuminating modes of access to the cultural moment. On 15 May 1958, for instance, Faulkner traveled to Lexington, Virginia, to

meet an audience at Washington & Lee University. Half an hour into the session, a man asks him for his “views of

the Supreme Court decision.” At that point in time, it was not necessary to say which decision was meant

– Brown v Board of Education had been decided four years earlier, and the implementation of its mandate to

abolish segregated schools had created a crisis in southern culture. In the groan of the white people in the room, in their

nervous laughter as Faulkner seems initially to deflect the question, and then in the silence that greets his longer answer, I

think we have audible proof of how tense the moment was

. In others ways, too, being able to overhear the sessions enriches the story they tell. For example, Faulkner in the

University makes no attempt to represent the reactions of Faulkner's audiences, although those often provide us with

illuminating modes of access to the cultural moment. On 15 May 1958, for instance, Faulkner traveled to Lexington, Virginia, to

meet an audience at Washington & Lee University. Half an hour into the session, a man asks him for his “views of

the Supreme Court decision.” At that point in time, it was not necessary to say which decision was meant

– Brown v Board of Education had been decided four years earlier, and the implementation of its mandate to

abolish segregated schools had created a crisis in southern culture. In the groan of the white people in the room, in their

nervous laughter as Faulkner seems initially to deflect the question, and then in the silence that greets his longer answer, I

think we have audible proof of how tense the moment was

. I also enjoy hearing the response of the freshmen (“First-Year men,” in UVA parlance) in Irby

Cauthen’s class to Faulkner’s answer to a question from Gwynn about Drusilla, the young woman in The

Unvanquished who, after her father and brothers have been killed fighting for the Confederacy, cuts her hair, puts on a

uniform, arms herself and rides off with Col. Sartoris’ unit “astride” a horse (rather than sitting

side saddle) to “kill Yankees.” The laughter of the young men at an all-male college that seems likely to be

increasingly faced with pressure to admit women (the other form of “integration” in the air of the time)

sounds awfully relieved

. I also enjoy hearing the response of the freshmen (“First-Year men,” in UVA parlance) in Irby

Cauthen’s class to Faulkner’s answer to a question from Gwynn about Drusilla, the young woman in The

Unvanquished who, after her father and brothers have been killed fighting for the Confederacy, cuts her hair, puts on a

uniform, arms herself and rides off with Col. Sartoris’ unit “astride” a horse (rather than sitting

side saddle) to “kill Yankees.” The laughter of the young men at an all-male college that seems likely to be

increasingly faced with pressure to admit women (the other form of “integration” in the air of the time)

sounds awfully relieved

.

.

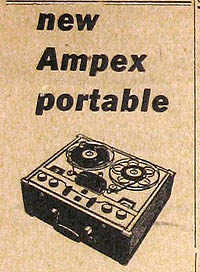

The quality of the audio you'll hear at this archive is uneven, for a number of reasons. By our standards, the equipment used

was fairly primitive, and being run by academics, not technicians; background noises on some of the tapes are forms of static from

the recorder itself. Only one microphone was used, and because Faulkner was so soft-spoken, it had to be placed immediately in

front of him, which means questions and comments from others in the room are often difficult to hear, and frequently inaudible.

And the tapes themselves, nearly 40,000 feet of fragile plastic strips, had held onto the magnetic records of voices and coughs,

laughter and applause for almost half a century before the Library began to digitize them, further degrading their fidelity to

those moments in 1957 and 1958. One tape, from a class session on 9 March 1957, is so difficult to listen to that we decided not

to transcribe the first 28 minutes of it, containing Faulkner's reading of “Was” (though you can hear it if

you choose the “Play Entire Recording” option for that session, or you can hear him reading

“Was” much more clearly on 8 May 1957). On the transcripts, whenever we weren’t certain of a

reading, we put brackets around the [word] or [group of words]. Words or phrases we couldn’t make out at all are

indicated with ellipses, like this: [...]. Sometimes an entire question is inaudible, but usually one can get the gist of it from

Faulkner’s answer; he is almost always responsive to the specific question being asked. (And if you hear something we

couldn’t, please let us know; an electronic publication can be amended as often as needed.)

The quality of the audio you'll hear at this archive is uneven, for a number of reasons. By our standards, the equipment used

was fairly primitive, and being run by academics, not technicians; background noises on some of the tapes are forms of static from

the recorder itself. Only one microphone was used, and because Faulkner was so soft-spoken, it had to be placed immediately in

front of him, which means questions and comments from others in the room are often difficult to hear, and frequently inaudible.

And the tapes themselves, nearly 40,000 feet of fragile plastic strips, had held onto the magnetic records of voices and coughs,

laughter and applause for almost half a century before the Library began to digitize them, further degrading their fidelity to

those moments in 1957 and 1958. One tape, from a class session on 9 March 1957, is so difficult to listen to that we decided not

to transcribe the first 28 minutes of it, containing Faulkner's reading of “Was” (though you can hear it if

you choose the “Play Entire Recording” option for that session, or you can hear him reading

“Was” much more clearly on 8 May 1957). On the transcripts, whenever we weren’t certain of a

reading, we put brackets around the [word] or [group of words]. Words or phrases we couldn’t make out at all are

indicated with ellipses, like this: [...]. Sometimes an entire question is inaudible, but usually one can get the gist of it from

Faulkner’s answer; he is almost always responsive to the specific question being asked. (And if you hear something we

couldn’t, please let us know; an electronic publication can be amended as often as needed.)

Transcribing speech into text involves other editorial decisions. We don't try to reproduce all the sounds on the tapes. Since

making these recordings usable was one of our major goals, we chose to omit anything that simply sounded like a form of hesitancy

– er, uh, &c., but do try to include all the words that are spoken. When Faulkner is reading one of his texts,

we follow his voice for the words, but the punctuation in the readings (which are displayed in dark red

type) is derived from the first book edition of each story. Punctuation in the transcribed questions and answers is

based on what we hear, subject to the larger desire to make the transcripts both accurate and readable. Pauses are not marked, no

matter how long they are. Unless you listen to an entire recording, you won’t hear most of the pauses between exchanges,

and you should use the “Play Entire Recording” button at least once, to get a sense of how frequently silence

fell over the room, and how comfortable Faulkner was about waiting those silences out.

Transcribing speech into text involves other editorial decisions. We don't try to reproduce all the sounds on the tapes. Since

making these recordings usable was one of our major goals, we chose to omit anything that simply sounded like a form of hesitancy

– er, uh, &c., but do try to include all the words that are spoken. When Faulkner is reading one of his texts,

we follow his voice for the words, but the punctuation in the readings (which are displayed in dark red

type) is derived from the first book edition of each story. Punctuation in the transcribed questions and answers is

based on what we hear, subject to the larger desire to make the transcripts both accurate and readable. Pauses are not marked, no

matter how long they are. Unless you listen to an entire recording, you won’t hear most of the pauses between exchanges,

and you should use the “Play Entire Recording” button at least once, to get a sense of how frequently silence

fell over the room, and how comfortable Faulkner was about waiting those silences out.

There are two additional transcription conventions I should explain. Following standard modern publishing practice, we decided not

to capitalize the words “northern” or “northerner,” “southern” or

“southerner.” But it seemed true to both the spirit of that time and the way the words are actually deployed

by the people who use them on these tapes to transcribe “north” as “North” and

“south” as “South.” That choice seems unproblematic, though I think it’s important to note that when the people on these tapes talk

about “the South,” they seem invariably to mean just white southerners. That brings me to the other

choice we had to make, about an issue that is (rightly) much more troubling for us than for most Americans fifty years ago. You

will hear Faulkner say the word “nigger” on a few of these tapes. When he reads “Was,” the

word is spoken by characters in the story, but on at least three occasions Faulkner uses the word speaking as himself. To me, this

word is more obscene than whatever profanity the convict uses at the end of “Old Man” and that Faulkner chose

neither to print nor, when he read that line to a freshman class, to speak

. When Gwynn and Blotner published Faulkner's remarks for the larger national and international audience they knew their book

would reach, they silently replaced the word with “Negro.”

*

But Faulkner's use of it is a part of the complex story these tapes tell, about him and about this time and place. He and his

all-white audiences talk a lot about African Americans, though of course they never use that term. Sometimes they use

“colored,” but the term they use most often is “Negro.” At least, that’s the way

I’ve chosen to transcribe the word they use. In most cases not capitalizing the term would probably capture the

way it’s being said (and defined) more accurately. (The Cavalier Daily, for instance, typically prints

“negro” throughout these years.) And in the southern accents on these tapes, especially Faulkner’s,

the word sometimes sounds so much like “nigger” that “Negro” seems euphemistic. You can

hear both “nigger” and “Negro” in Faulkner's reply to another student in Prof.

Cauthen’s class on The Unvanquished, and this one passage can help us appreciate both the phonetic and the

ideological complexity of his racial vocabulary. As he elaborates the answer he pronounces the words in several different ways,

and goes on to remind his listeners that Ringo, the black boy being discussed, is smarter and more resourceful than Bayard, the

white boy

. When Gwynn and Blotner published Faulkner's remarks for the larger national and international audience they knew their book

would reach, they silently replaced the word with “Negro.”

*

But Faulkner's use of it is a part of the complex story these tapes tell, about him and about this time and place. He and his

all-white audiences talk a lot about African Americans, though of course they never use that term. Sometimes they use

“colored,” but the term they use most often is “Negro.” At least, that’s the way

I’ve chosen to transcribe the word they use. In most cases not capitalizing the term would probably capture the

way it’s being said (and defined) more accurately. (The Cavalier Daily, for instance, typically prints

“negro” throughout these years.) And in the southern accents on these tapes, especially Faulkner’s,

the word sometimes sounds so much like “nigger” that “Negro” seems euphemistic. You can

hear both “nigger” and “Negro” in Faulkner's reply to another student in Prof.

Cauthen’s class on The Unvanquished, and this one passage can help us appreciate both the phonetic and the

ideological complexity of his racial vocabulary. As he elaborates the answer he pronounces the words in several different ways,

and goes on to remind his listeners that Ringo, the black boy being discussed, is smarter and more resourceful than Bayard, the

white boy

. Unless there's no doubt in my mind about the term Faulkner uses, I’ve chosen to compromise (or maybe to engage in

evasion myself) and represent the sound of the word as “Negro.” Because this is an audio archive, you can

listen for yourself, and make up your own mind about how the African Americans in Faulkner's fiction and in

“southern” fact are referred to and, more importantly, represented.

. Unless there's no doubt in my mind about the term Faulkner uses, I’ve chosen to compromise (or maybe to engage in

evasion myself) and represent the sound of the word as “Negro.” Because this is an audio archive, you can

listen for yourself, and make up your own mind about how the African Americans in Faulkner's fiction and in

“southern” fact are referred to and, more importantly, represented.

Contexts

Below you’ll find the recording, essays and articles on Faulkner’s residency mentioned at the start of

this introduction, as well as images and other items that we hope will help you appreciate the environment in which the recordings

were made. These ancillary materials will also explain some of the specific issues that arise on the tapes. At his press

conference on 20 May 1957, for instance, Faulkner mentions "the unhappy business of the invitations" as an example of Virginia's

failure to live up to its role as the leader among the southern states

. (This clip also contains an instance of the silences noted earlier.) The Cavalier Daily ran an editorial on that event about a month earlier. You’ll find that article and additional similar

materials in the other three pages in this CONTEXTS section – on Faulkner, the U.S. and UVA in the late

1950’s. Links to those pages are at the top of this page.

. (This clip also contains an instance of the silences noted earlier.) The Cavalier Daily ran an editorial on that event about a month earlier. You’ll find that article and additional similar

materials in the other three pages in this CONTEXTS section – on Faulkner, the U.S. and UVA in the late

1950’s. Links to those pages are at the top of this page.

Recording of 1962 UVA Press Conference on Faulkner's Tenure

Essays on Faulkner and UVA

- Mr. Faulkner: Writer-In-Residence, by Joseph Blotner

- The Grounds and the Fury, by Ken Ringle (UVA ’61)

- Faulkner and an Undergraduate, by John A. Church (UVA ’59)

- Faulkner and UVA, by Gerald L. Cooper (College ’58, M.Ed. Guidance ’69))

- Learning Faulkner, by Ann Thomas Moore (M.A. English ’58))

- Memories of William Faulkner, by James W. Haskins (College ’63, Law ’66)

- Memories of “Bill” Faulkner with the IMP Society, by Jack Docherty (College ’61)

- Encountering Mr. Faulkner, by Joe Carroll (College ’61)

- Memory of William Faulkner, by Lloyd T. Smith, Jr. (College ’55, Law ’60)

- My Time with William Faulkner, by William Lecky (Architecture ’60)

- The Gentleman Hitch-Hiker, by By R. C. Greene (College ’61)

- Mr. Faulkner in My Classroom, by Robert Scholes

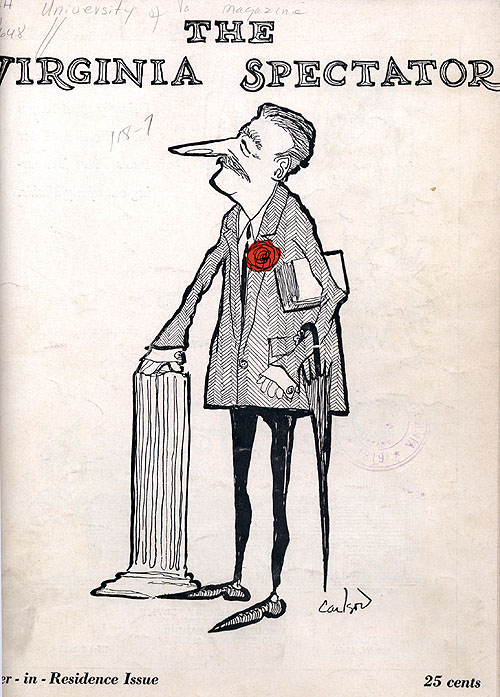

The “Writer-in-Residence Issue” of Virginia Spectator (April 1957):

Images from the “Writer-in-Residence Issue” —

Articles from the “Writer-in-Residence Issue” —

- Thorn for Edward

- The Personality of William Faulkner

- The Sound and the Flurry

- Views of a Writer-in-Residence

Images from the Faulkner Print Collection —

Cavalier Daily Articles on Faulkner —

- William Faulkner Accepts Invitation As First Of Writers-In-Residence (6 October 1956)

- Faulkner at the University (6 October 1956)

- Faulkner Arrives To Assume Role As Writer-in-Residence (13 February 1957)

- Faulkner Begins Stay As Writer-In-Residence (16 February 1957)

- Faulkner: First Impressions (16 February 1957)

- Faulkner Holds Public, Press Conferences (8 May 1957)

- "Jim Crow" Spectator (10 May 1957)

- From Jefferson Hall (17 May 1957)

- Faulkner Makes Public Interviews (22 May 1957)

- Writer-In-Residence Faulkner To Return Next Spring (25 October 1957)

- Faulkner Will Return in February (18 December 1957)

- Mississippi Writer Here Until June; Second Visit (4 February 1958)

- William Faulkner To Talk On Segregation Problem (19 February 1958)

- Mr. Faulkner On Segregation (25 February 1958)

- Film of Faulkner Book Opens New York Run (14 March 1958)

- Faulkner To Appear On Television In Filmed Class Discussion Sunday (15 March 1958)

- English Depart. Announces Faulkner Schedule (29 March 1958)

- Faulkner Arranges Final Appearance Before Public Friday In Rouss Hall (21 May 1958)

Charlottesville Daily Progress Articles on Faulkner —

- Mrs. Darden Will Receive Callers Tomorrow Afternoon at 'Carr's Hill' (31 January 1955)

- Faulkner Talks To Reporters About Integration, Virginians (15 February 1957)

- [Faulkner Photo] (16 February 1957)

- Faulkner Flying To Greece To See 'Requiem For A Nun' (16 March 1957)

- Faulkner Plans Reading Of His Work Before Public (8 May 1957)

- Hard, Fast Rule For Writers: Truthfulness, William Faulkner Tells High School Students (8 May 1957)

- Faulkner Declares Virginia Should Cherish Leadership (11 May 1957)

- Yoknapatawpha And Albemarle (25 May 1957)

- Faulkner Invited To Return To UVa (30 May 1957)

- Faulkner Reads From Novel, Describes Probable Sequel (31 May 1957)

- Faulkner to Return to UVa (24 October 1957)

- Faulkner is Back Again For Second Term at UVa (15 February 1958)

- Faulkner To Discuss Segregation (20 February 1958)

- Faulkner Plans Final Talk Friday (21 May 1958)

- Faulkner Would Like to Live Final Years in Albemarle (24 May 1958)

- Faulkner Plans to Spend Winter Here (13 November 1958)

- Mr. Faulkner In the Library (15 January 1959)

- William Faulkner To Leave in April (16 March 1959)

Selected Items from the UVA Faulkner Collections —

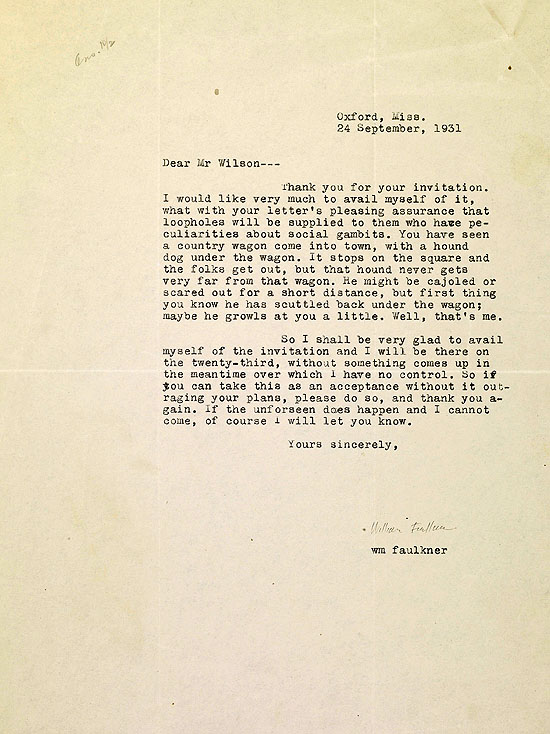

- Letter from Faulkner accepting his invitation to the Southern Writers Conference (24 September 1931)

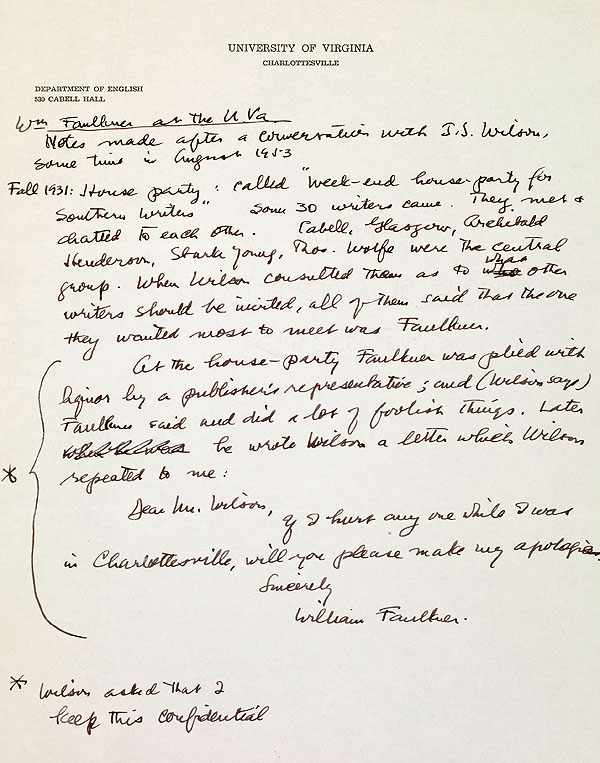

- Unsigned notes about Faulkner's behavior at the Southern Writers Conference (undated)

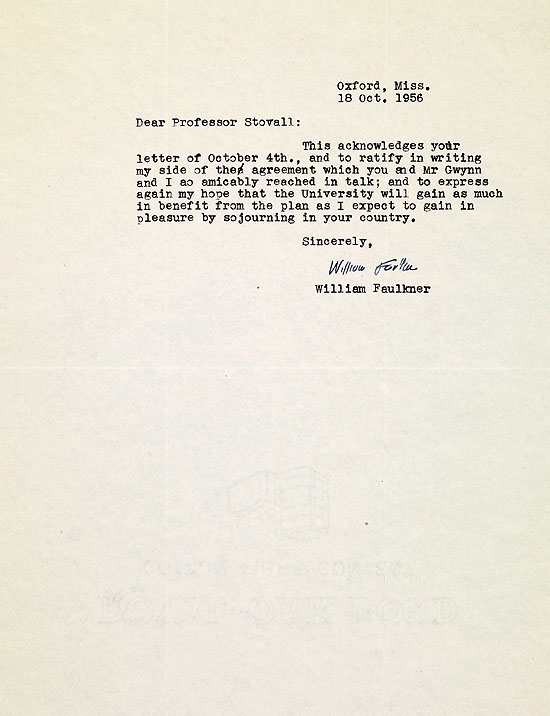

- Letter from Faulkner ratifying his first appointment as Writer-in-Residence (18 October 1956)

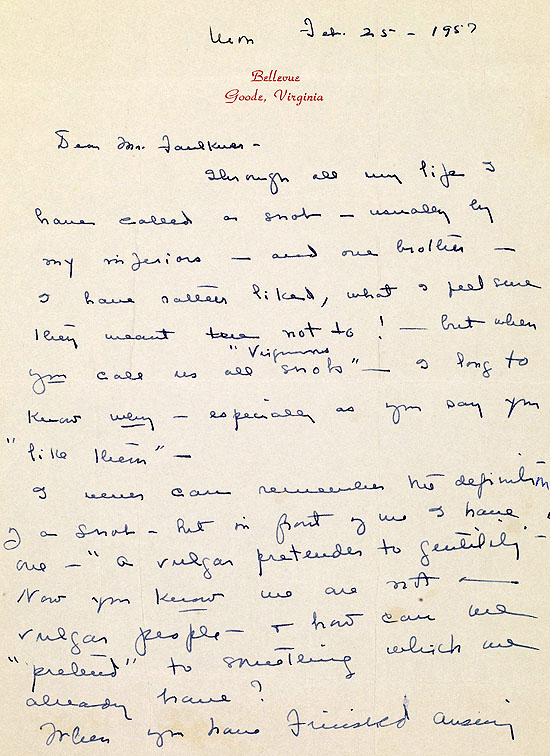

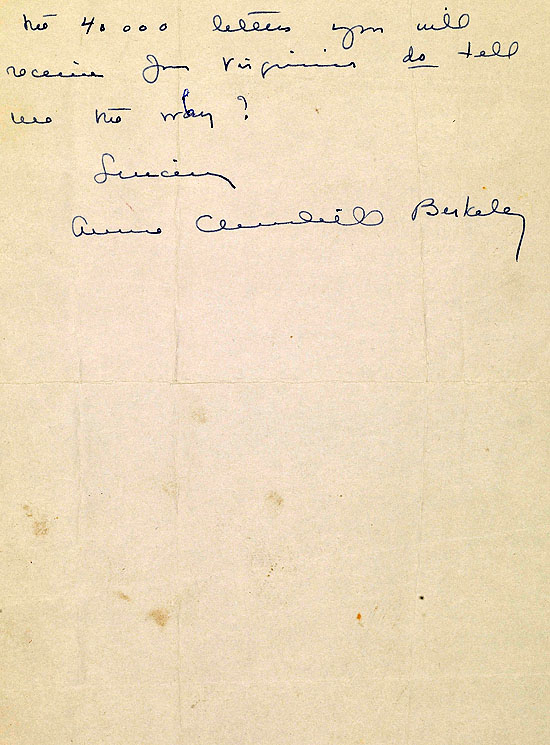

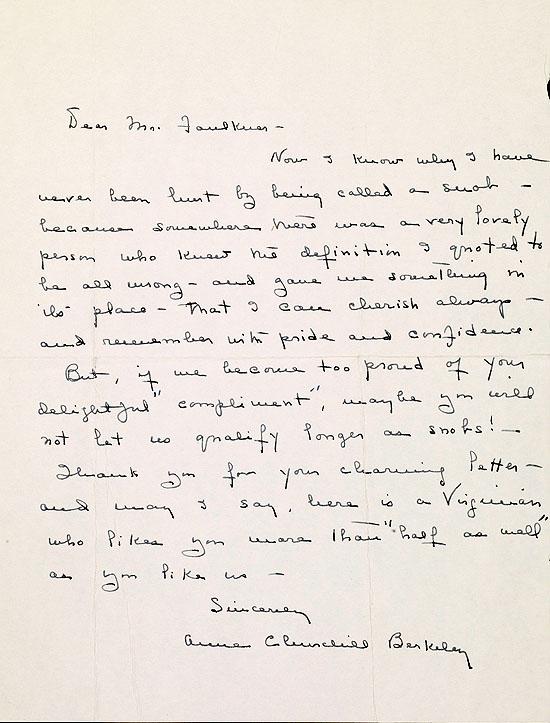

- Letter from Annie Churchill Berkeley asking Faulkner why he called all Virginians "snobs" (25 February 1957)

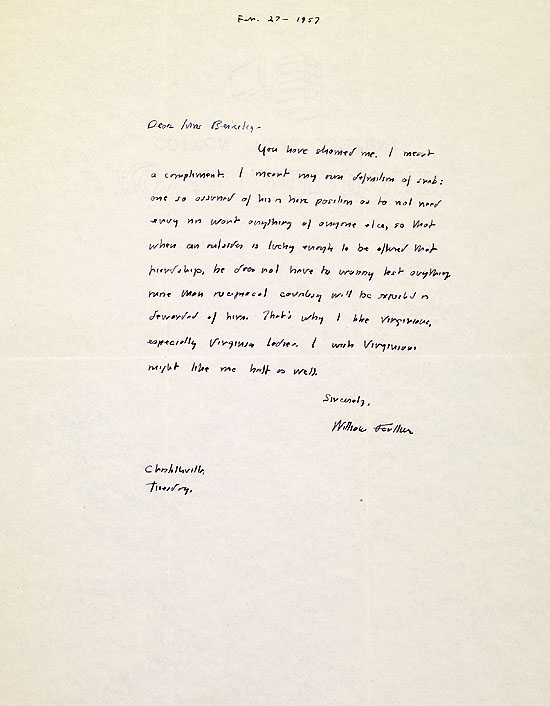

- Letter from Faulkner to Mrs. Berkeley, explaining his remark (27 February 1957 )

- Letter from Annie Churchill Berkeley to Faulkner (c. March 1957)

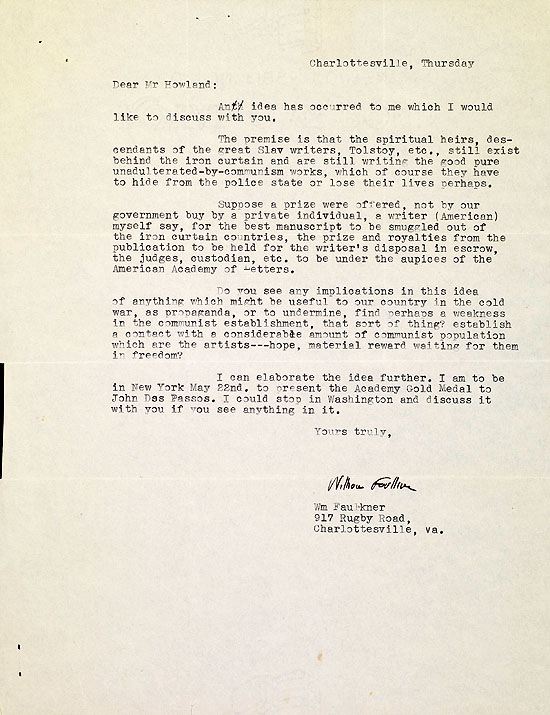

- Letter from Faulkner to Harold Howland proposing a prize for manuscripts smuggled through the iron curtain (c. 9 May 1957)

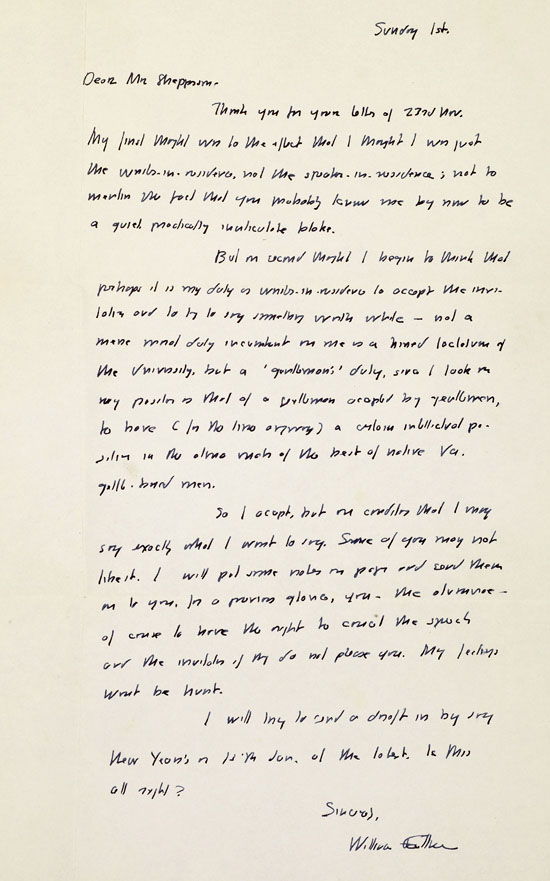

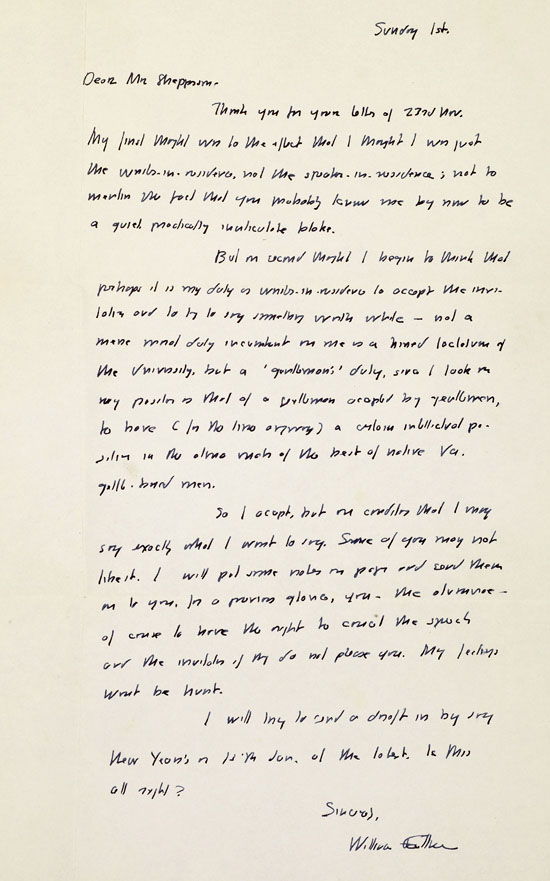

- Letter from Faulkner accepting invitation to address the UVA Club in Washington (1 December 1957)

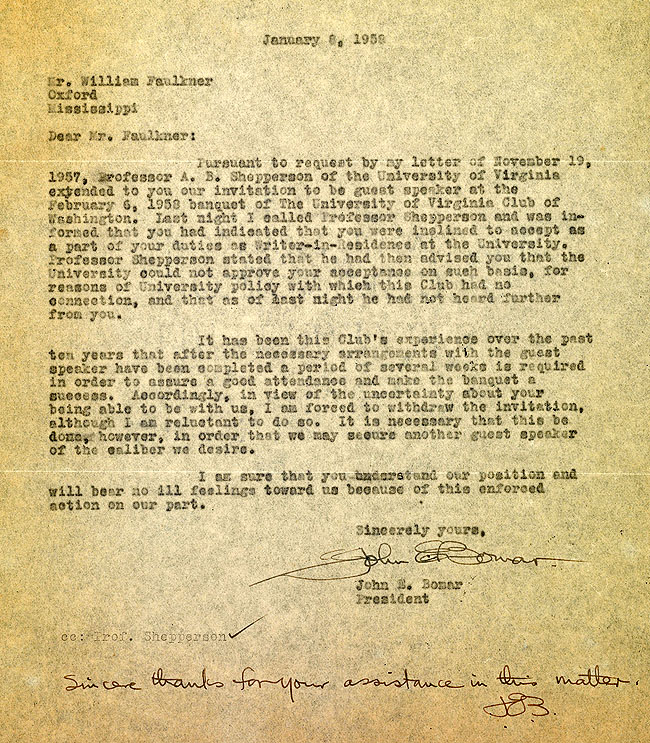

- Letter to Faulkner, withdrawing the invitation to address the UVA Club of Washington (8 January 1958)

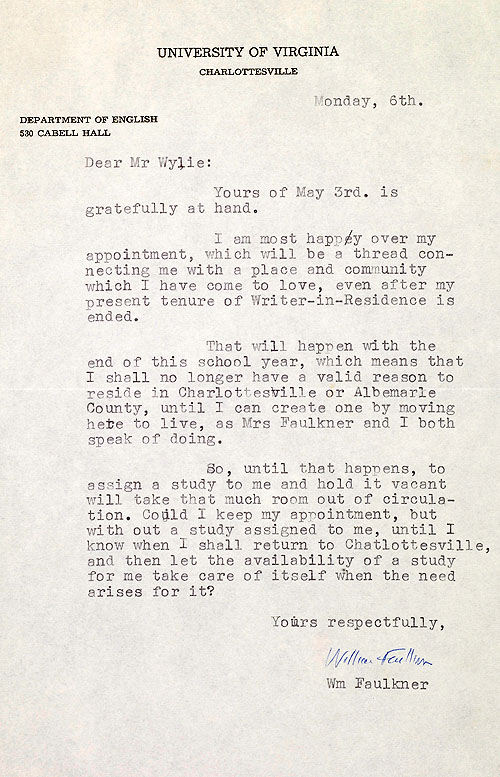

- Letter from Faulkner to John Cook Wylie, UVA Librarian, accepting appointment as a consultant to the Library (6 May 1958)

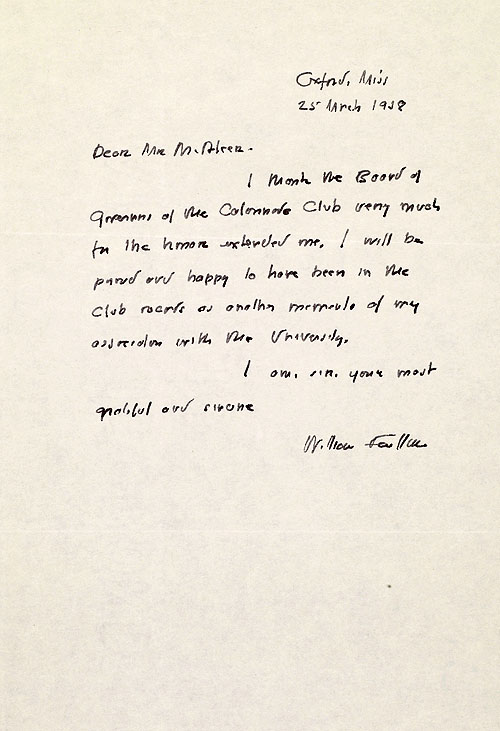

- Letter from Faulkner to Edward McAleer, accepting a membership in UVA's Colonnade Club (25 March 1958)

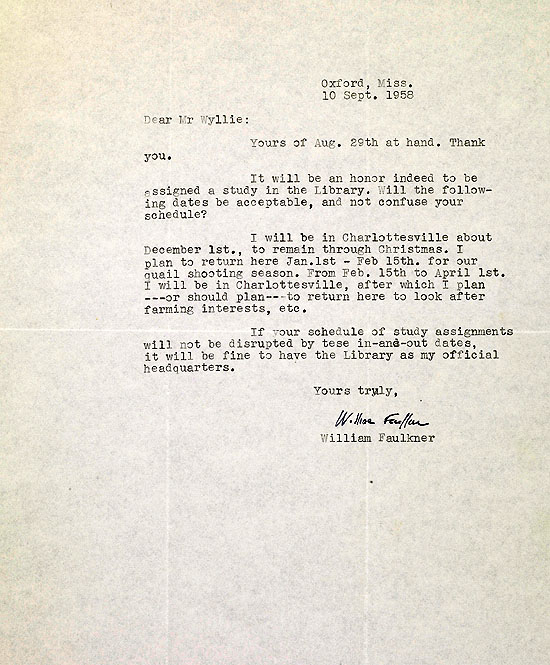

- Letter from Faulkner to John Cook Wylie, accepting offer of a study in Library (10 September 1958)

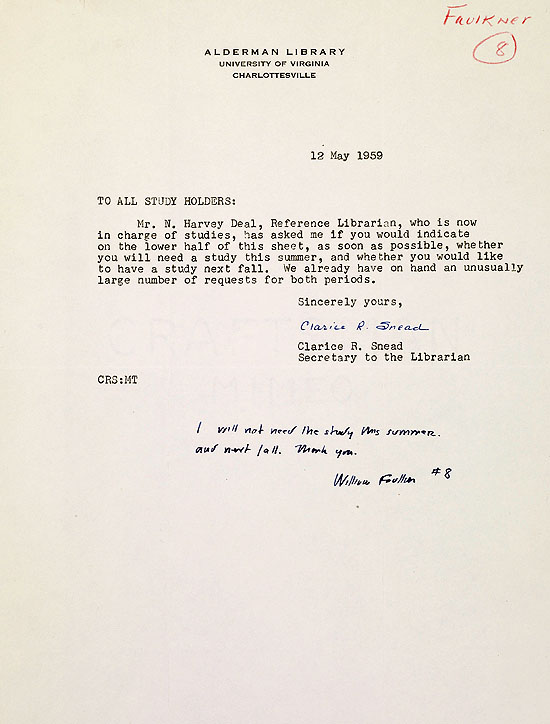

- Letter from Clarice Snead to Faulkner about his Library study, with his response (12 May 1959)

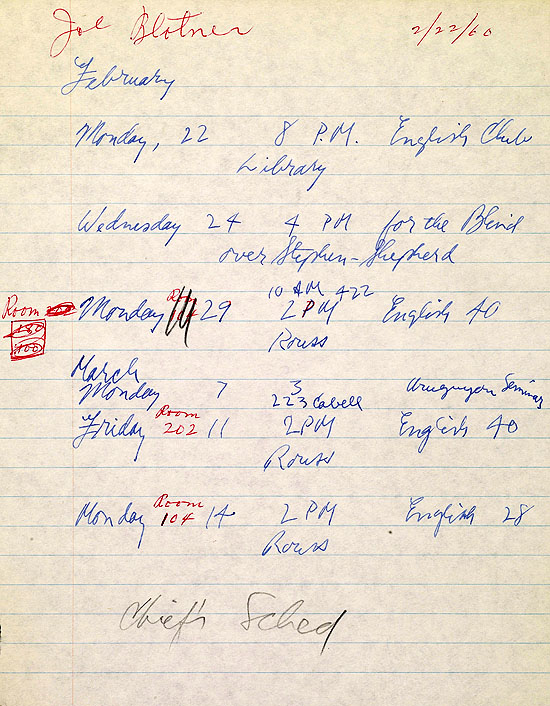

- Joseph Blotner's chart of Faulkner's UVA speaking engagements, February-March 1960 (22 February 1960)

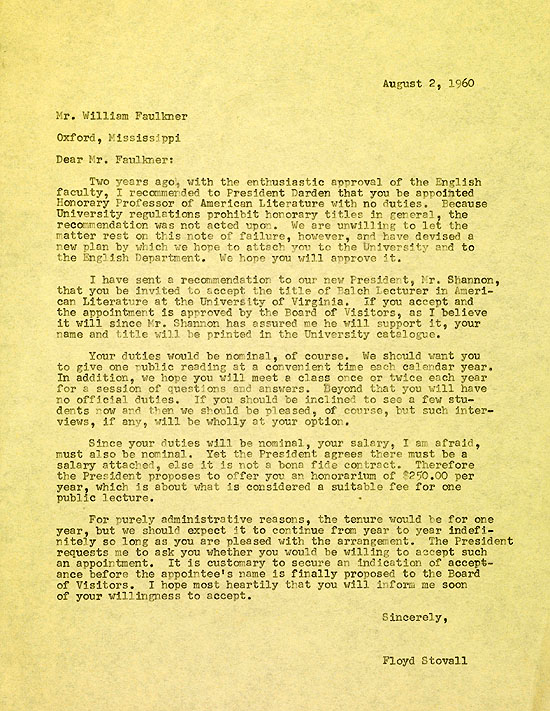

- Letter to Faulkner offering him an appointment as "Honorary Professor of American Literature." (2 August 1960)

- Letter from Faulkner about this appointment (25 August 1960)

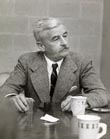

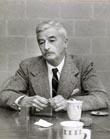

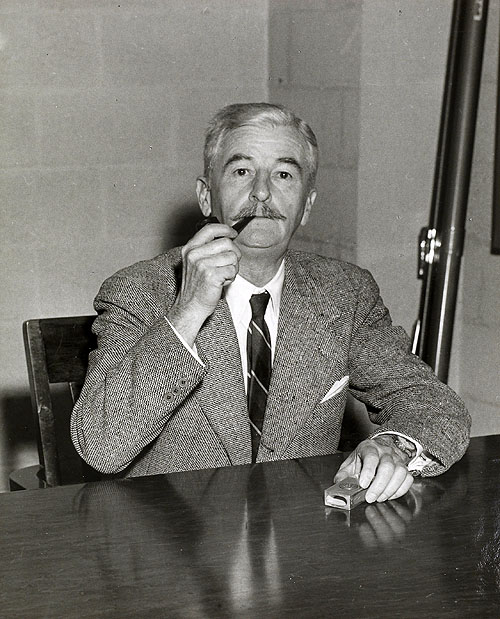

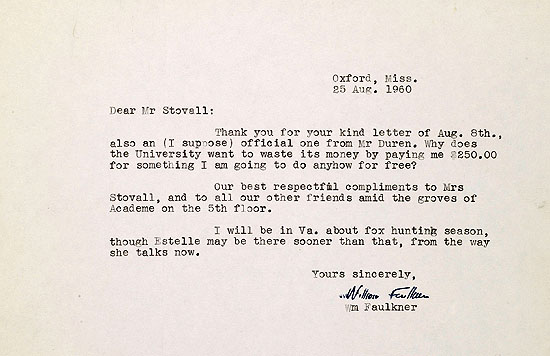

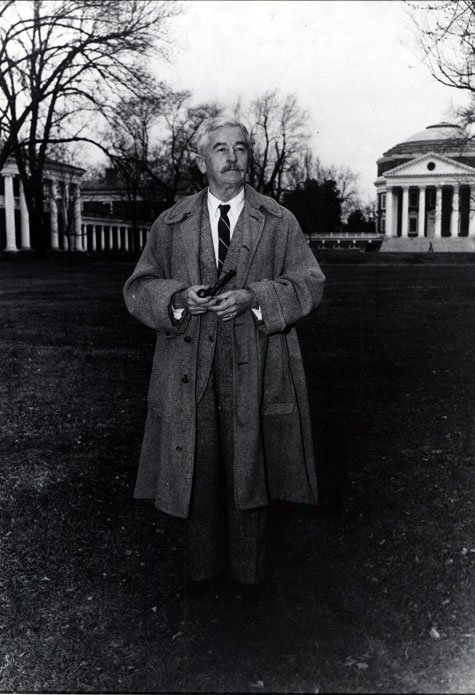

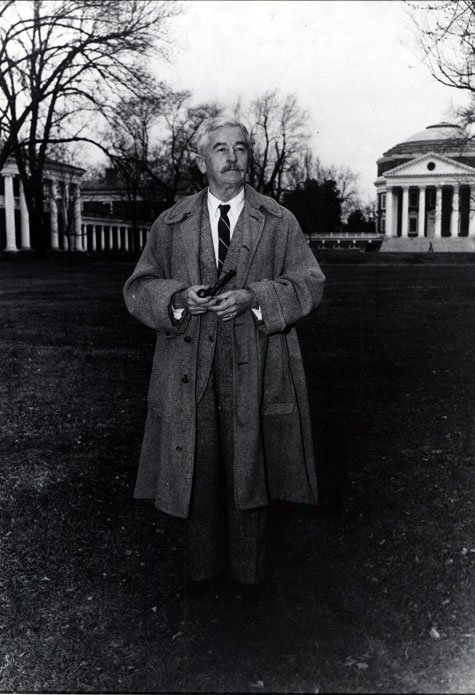

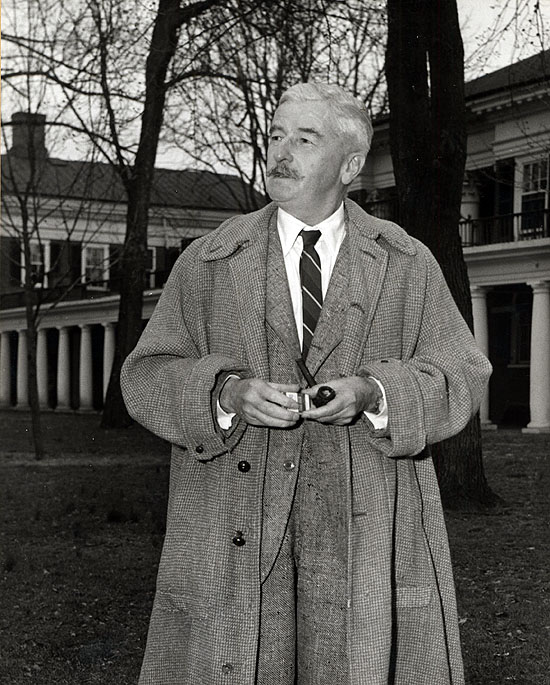

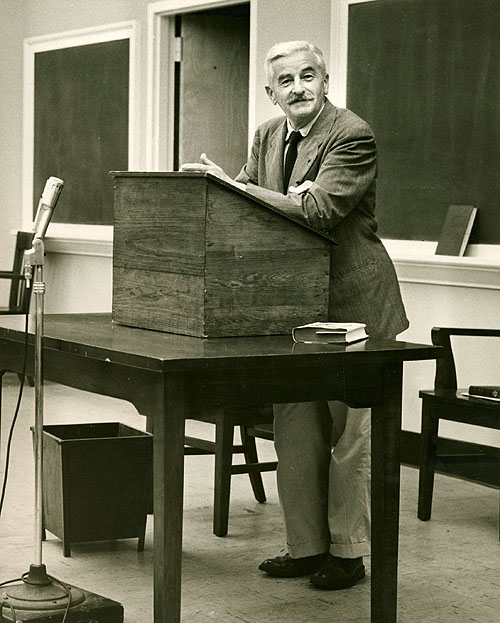

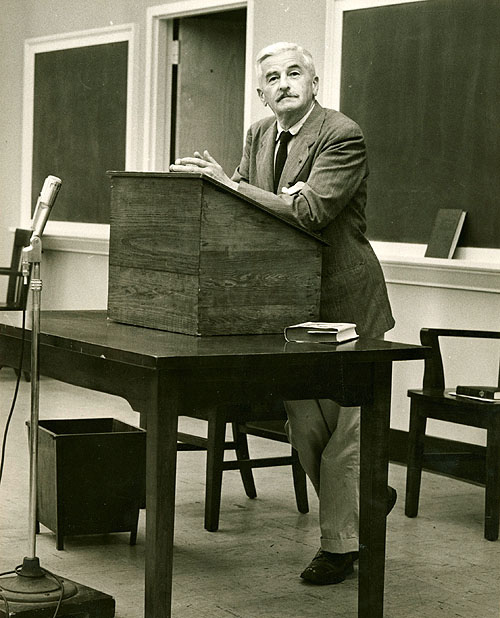

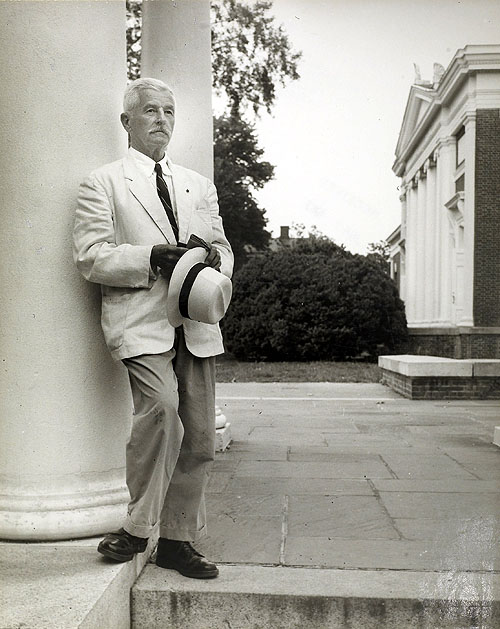

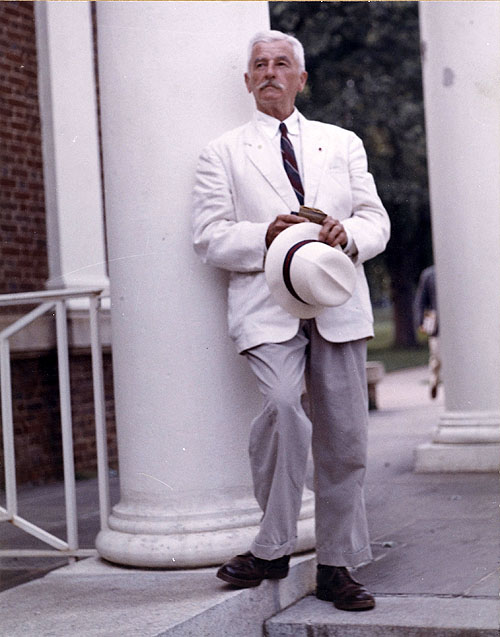

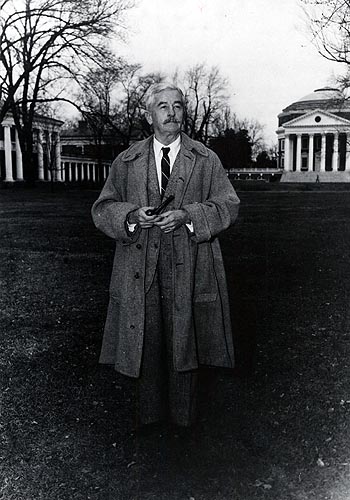

Below: William Faulkner on the Lawn at the University of Virginia, 15 February 1957 – his first day as Writer-in-Residence. Photograph by Ralph Thompson. [Digitization #000004470_0002]

Below: 1 December 1957 letter from William Faulkner to Prof. A. B. Shepperson, replying to his invitation to address the University of Virginia Club in Washington, D.C. Faulkner Papers, UVA Special Collections [Digitization #000003743_0063].

Transcription: Sunday 1st. Dear Mr. Shepperson – / Thank you for your letter of 23rd Nov. / My first thought was to the effect that I thought I was just / the writer-in-residence, not the speaker-in-residence; not to / mention the fact that you probably know me by now to be / a quiet, practically inarticulate bloke. / But on second thought I begin to think that / perhaps it is my duty as writer-in-residence to accept the invi- / tation and to try to say something worth while – not a / mere moral duty incumbent on me as a hired factotum of / the University, but a 'gentleman's' duty, since I look on / my position as that of a gentleman accepted by gentlemen, / to have (for the time anyway) a certain intellectual po- / sition in the alma mater of the best of native Va. / gentle-bred men. / So I accept, but on condition that I may / say exactly what I want to say. Some of you may not / like it. I will put some notes on paper and send them / on to you, for a previous glance, you – the alumnae – / of course to have the right to cancel the speech / and the invitation if they do not please you. My feelings / wont be hurt. / I will try to send a draft in by say / New Year's or 13th Jan. at the latest. Is this / all right? / Sincerely, William Faulkner

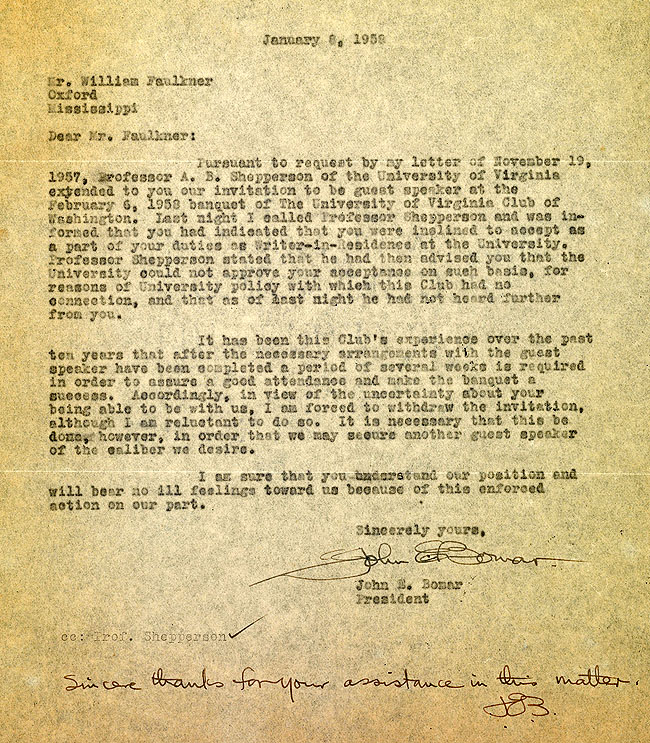

There's more to this story, though the details aren't known. Faulkner may have planned to talk about the Civil Rights movement, and resistance to it among white southerners, which was the subject of the speech he gave at his first appearance as Writer-in-Residence for 1958 – or the Club may have been afraid he was thinking of that, or some other controversial subject. In any case, 6 weeks later the Club's President wrote Faulkner to rescind the invitation, for reasons that seem specious, as you can see for yourself below. Faulkner Papers, UVA Special Collections [Digitization #000003743_0065].

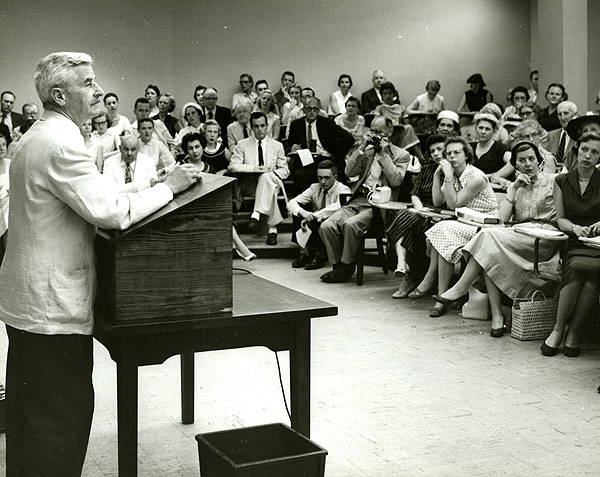

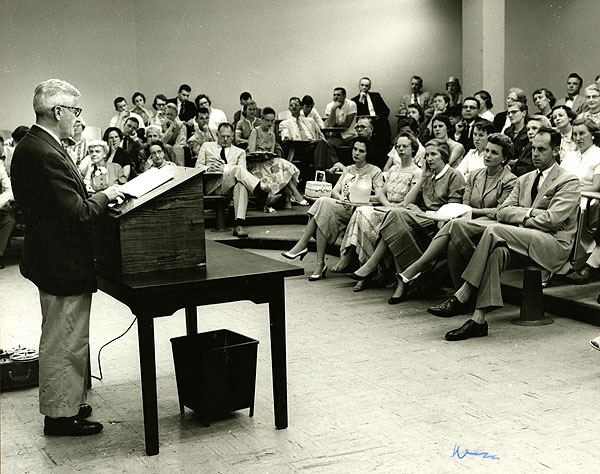

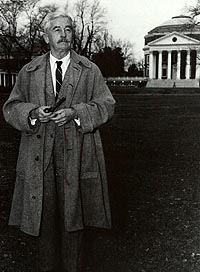

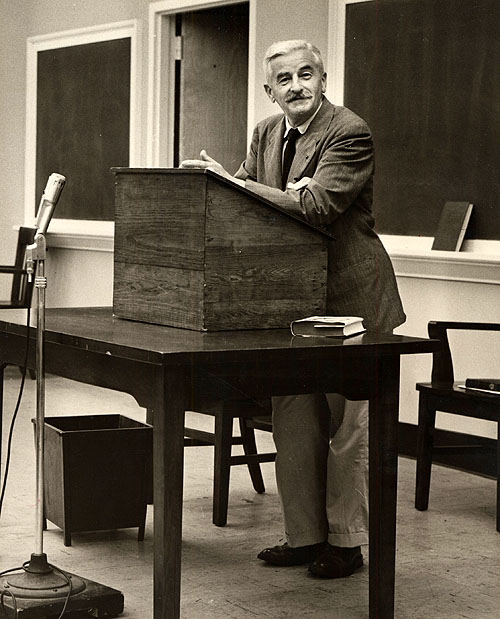

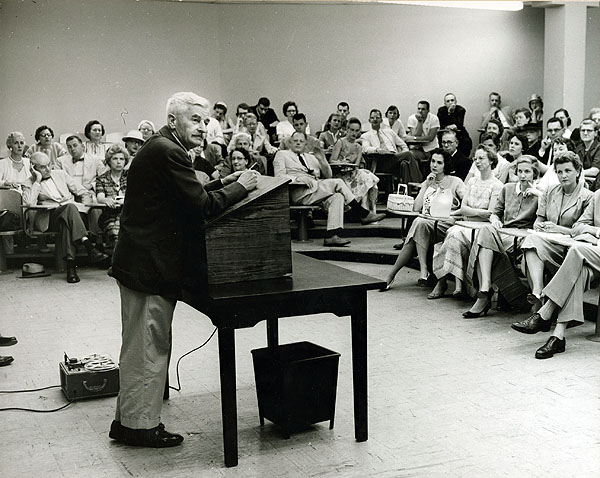

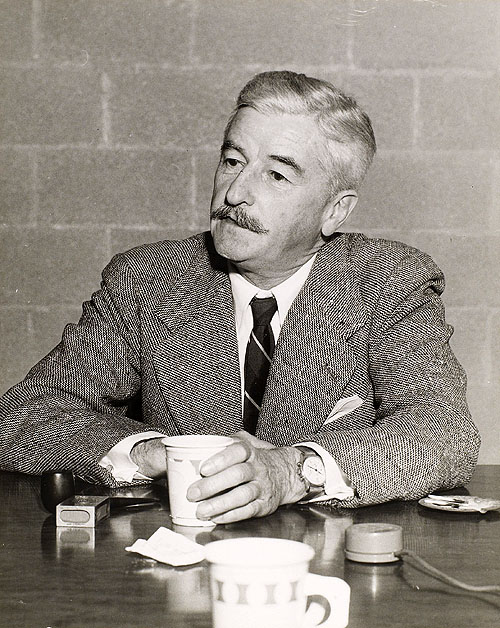

Below: Photo by Ralph Thompson of Faulkner in Cabell Hall with unidentified students (undated but c1957) [Print# 0189; Digitization# 000005733_0015].

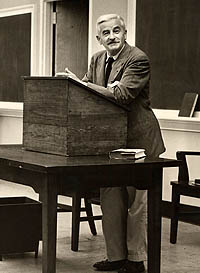

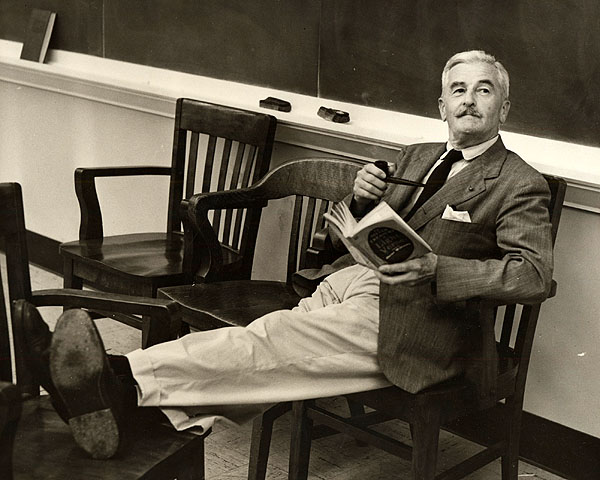

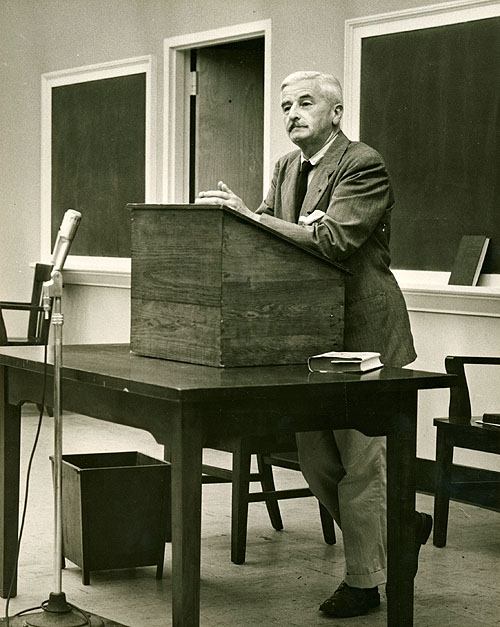

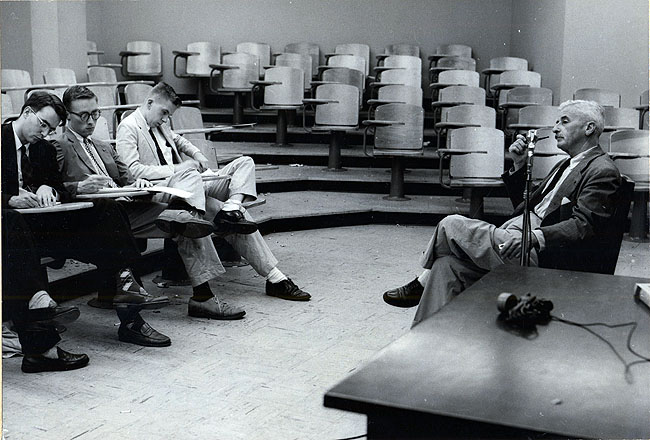

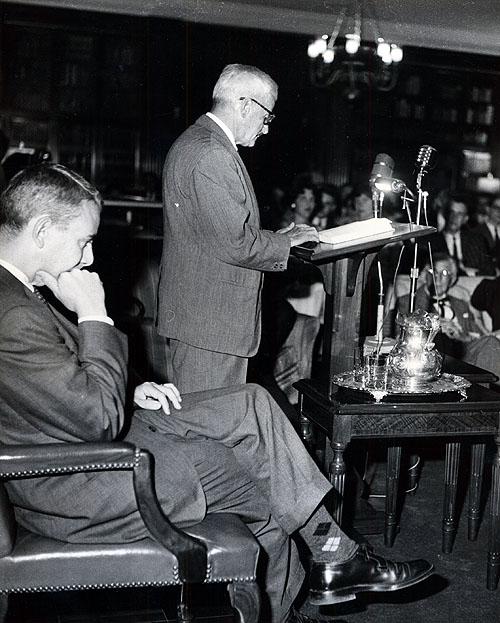

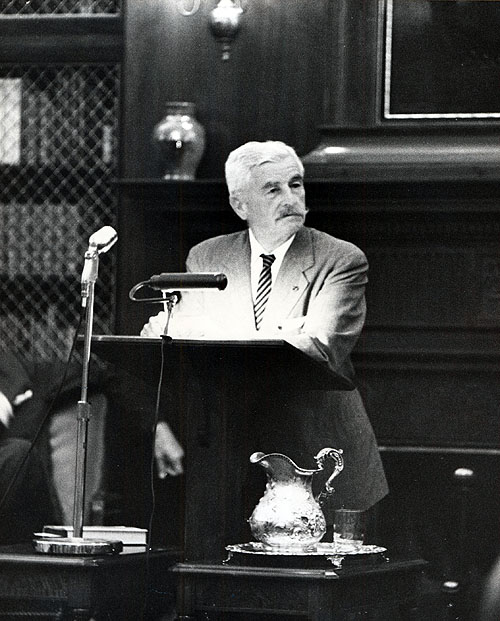

Below: William Faulkner in a Cabell Hall classroom at the University of Virginia, probably February 1957. Photograph by Ralph Thompson. [Digitization #000004470_0015]

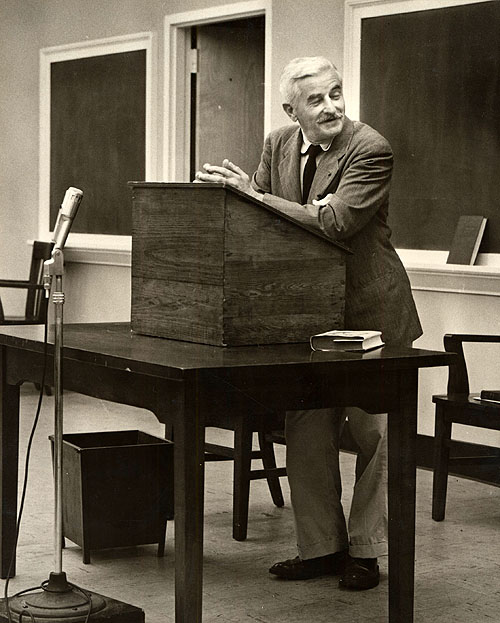

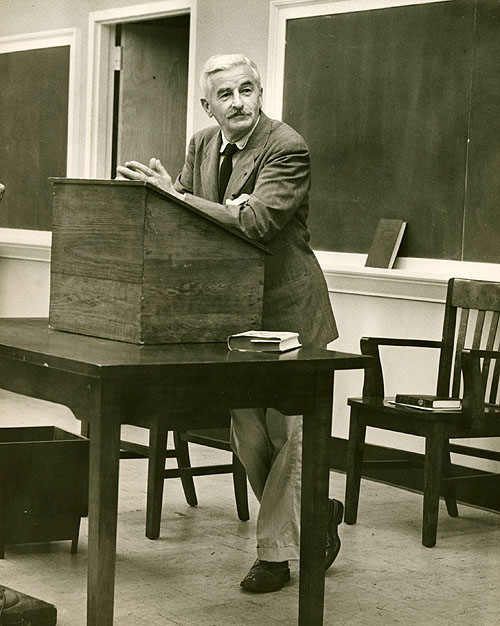

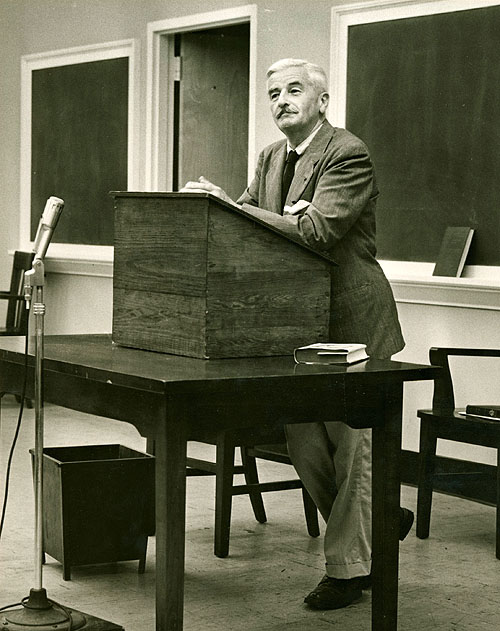

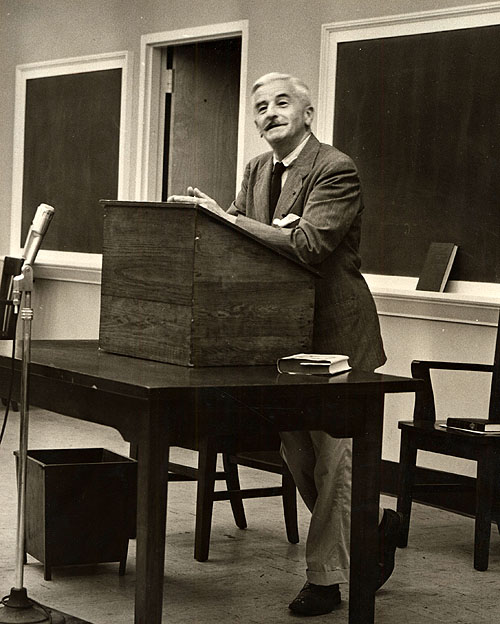

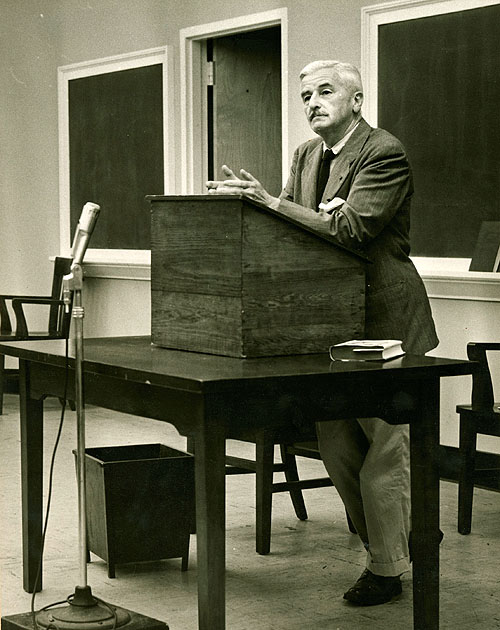

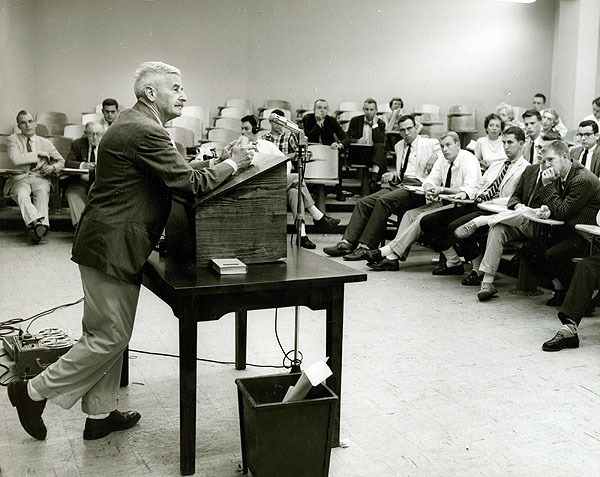

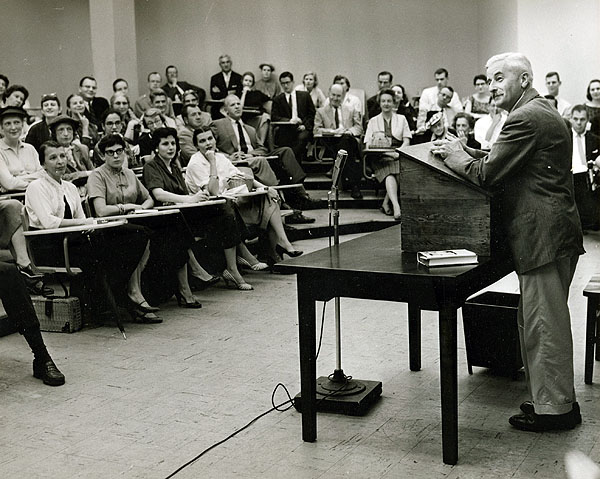

Below: Photo by Ralph Thompson of Faulkner in Rouss Hall [Print# 0218]. Note woman in front row with fan. Faulkner called this windowless classroom, where most of his UVA sessions took place, "the black hole of Calcutta" because it was so hot.

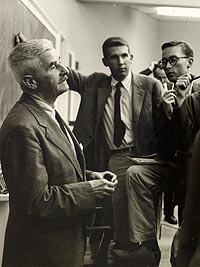

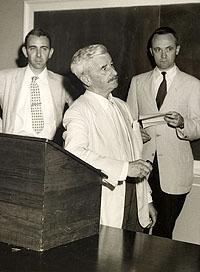

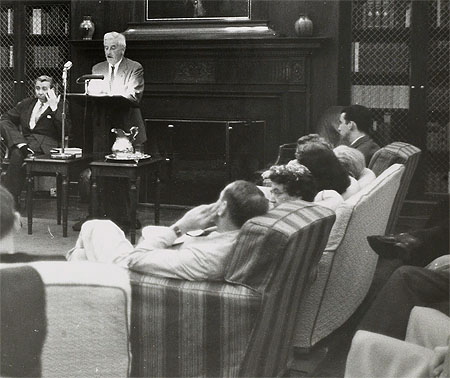

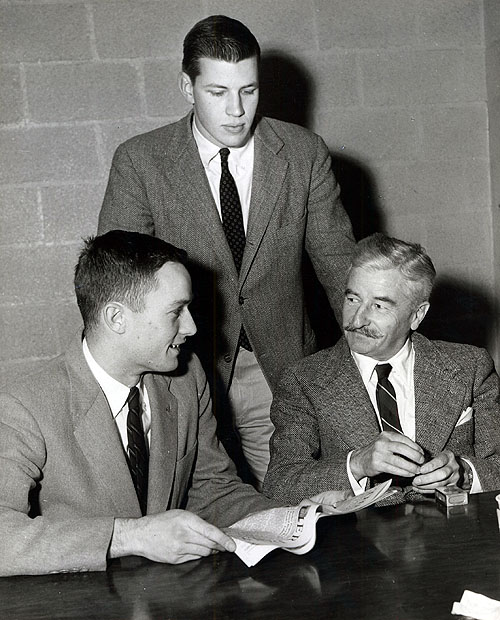

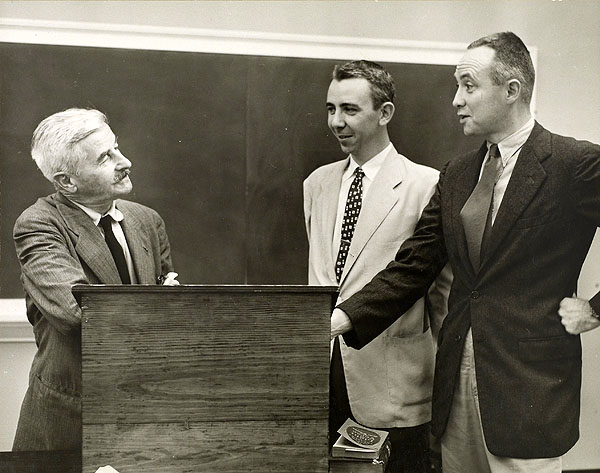

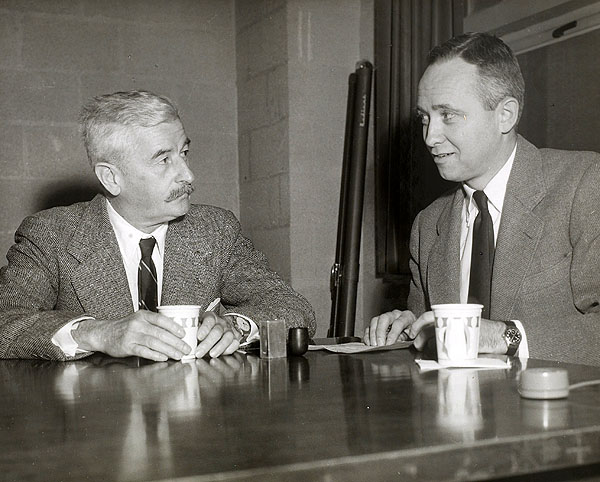

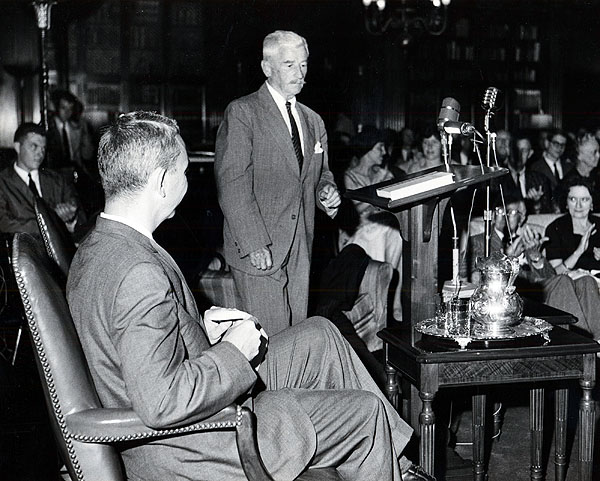

Below: Photo by Ralph Thompson of Faulkner in Rouss Hall with (left to right) Joseph Blotner, Frederick Gwynn, unidentified man. Caption on back: "May 15 [1957] after meeting with the public. Photo by Ralph Thompson." [Print# 0166; Digitization# 000005733_0009].

The Cavalier Daily 29 March 1958: 1

English Depart. Announces Faulkner Schedule

The English Department has announced the classroom schedule of writer-in-residence, William Faulkner, for the remainder of the semester.

The schedule is as follows: Thurs., 1 May, 10:00 a.m. in 337 Cabell Hall for Eng. 28, (McAleer), Subject – "Portable Faulkner"; Fri., 2 May, 4:00 p.m. in 202 Rouss Hall for Eng. 22, 28 (Blotner) and Eng 124, Subject – "The Sound and the Fury" and "As I Lay Dying".

Tues., 6 May in Radio Cabell Hall for Eng. 32: Language (Stephenson), Subject – Language and Dialect; Thurs., 8 May, 4:00 p.m. in 202 Rouss Hall for Eng. 3-4: Sophomore English (Murrah) and Eng. 124, Subject "The Bear" and "Absalom, Absalom!"

Mon., 12 May, 4:00 p.m. in 202 Rouss Hall for Virginia Colleges, Subject – Writing; Thurs., 15 May, 3:30 p.m. in Lee Chapel for Washington and Lee University, Subject – Writing.

Mon., 19 May, 4:00 p.m. in 202 Rouss Hall for Eng. 2 (Weston), Subject – "As I Lay Dying"; Fri., 23 May 4:00 p.m. in 202 Rouss for University and City public (Eng. Dept. Secretary), Subject – Writing.

Classes are open to all members of the University, with permission of the instructor.

©1958 The Cavalier Daily

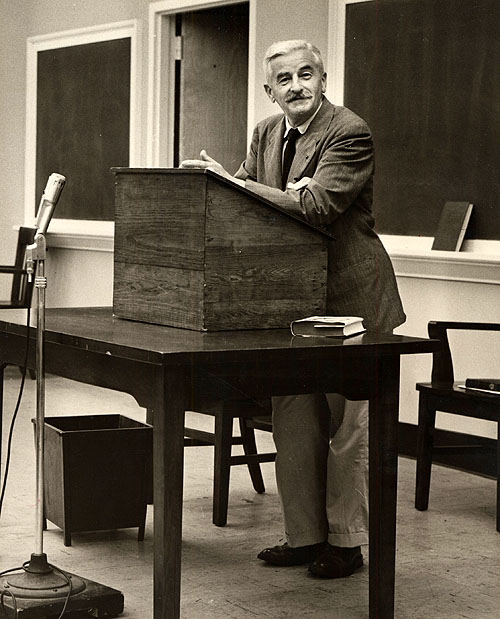

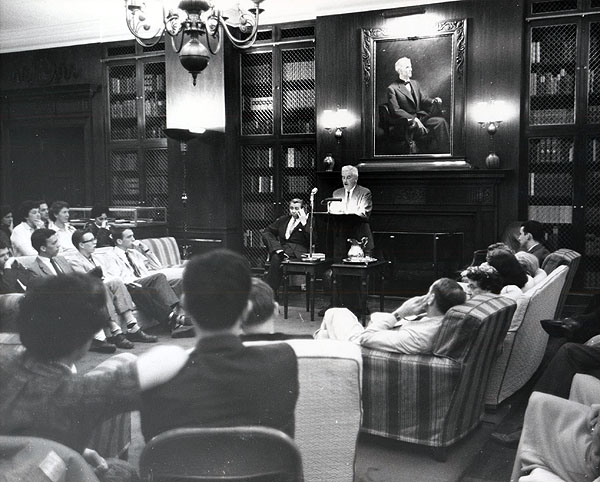

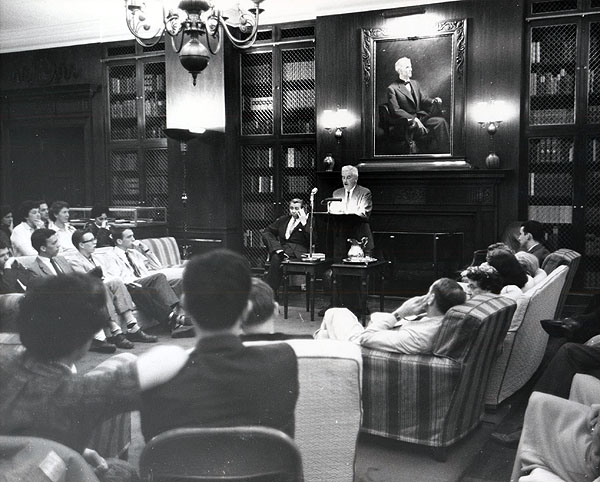

Below: Photo by Ralph Thompson of Faulkner in Rouss Hall (undated but c1957). [Print# 0191; Digitization# 000005733_0017].

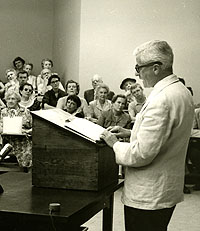

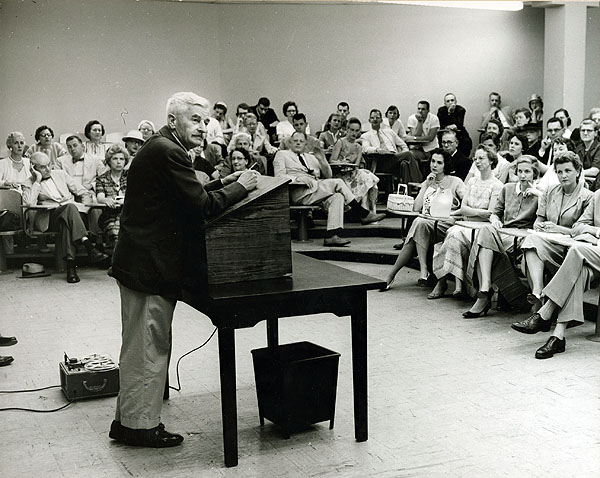

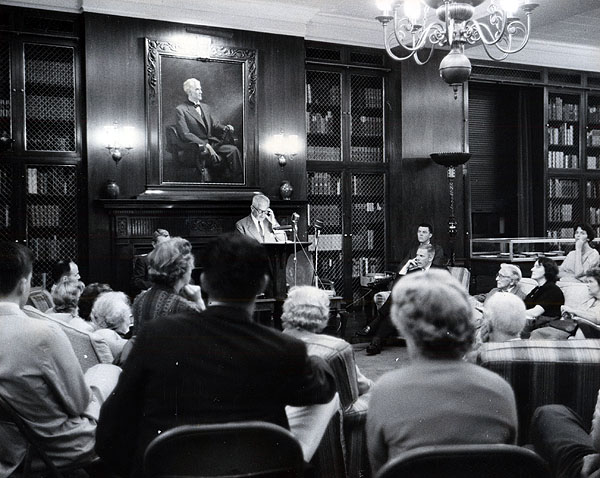

Below: William Faulkner with townspeople in 202 Rouss Hall, University of Virginia, Spring 1957. Photograph by Ralph Thompson. [Digitization #000004470_0028]

The Cavalier Daily 16 April 1957: 2

Mistaken Invitation And A Damaged Reputation

Virginia lost a genuine opportunity to create goodwill in the race issue last week when the State Chamber of Commerce withdrew two invitations accidentally extended to Negroes for a "Distinguished Virginians Dinner" in Richmond on May 17. The invitations were issued in the names of Frank A. Ernst, Chamber president, and Thomas B. Stanley, Governor of Virginia, through what was termed by Ernst a "clerical error."

Newsmen were able to obtain nothing more than a "no comment" from the Governor's office when they tried to get an official explanation. The Chamber of Commerce stated that personal letters had gone to both Negroes asking that they return the invitations. One of these persons has answered that he will attend the dinner unless Governor Stanley personally rescinds the offer.

If this "Distinguished Virginians" banquet is to be what the name implies, we can see no good reason why it should not include Virginians of both races. Certainly, once colored persons had actually been invited – through error or not – it was a mistake to retract their invitations. A far more sensible course would have been public welcome of the Negroes as proof that we respect distinguished Virginians regardless of race even though we are not ready to bring their race into the white schools of our educational system.

The date of the dinner, May 17, serves as an ominous reminder to us of the damage done to our State in the current racial crisis. It was on this date in 1954 that the U.S. Supreme Court handed down the original decision outlawing race segregation in public schools.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

Mr. Faulkner: Writer-In-Residence

By Joseph Blotner

[This essay was first published in The Virginia Quarterly Review (Spring 2001), then as a chapter in Mr. Blotner’s autobiography, An Unexpected Life (Louisiana State University Press, 2005). It is reprinted here with the generous permission of the Blotner family and VQR.]

It was just as well, for Fred Gwynn and me and our hopes for the University of Virginia’s Writer-in-Residence Program in 1955, that our memories of Charlottesville did not stretch back more than a few years. Others recalled a signal event in its cultural life more than two decades before. Ellen Glasgow, Virginia novelist and literary grande dame, felt that Southern writers like herself living in New York were kept from seeing each other by their isolation and the bustle of metropolitan life. She proposed to UVa. English Department head James Southall Wilson a gathering of 20 or 30 leading writers in some pleasant place where they could talk with each other. The president of the university endorsed the idea, and the resulting committee invited 34, including Thomas Wolfe, James Branch Cabell, and William Faulkner. Against his inclination and better judgment, Faulkner made one of the number on Oct. 23, 1931, eagerly awaited because of the publicity that had greeted his sensational novel Sanctuary.

Genuinely shy, and convivial mainly with a few friends and then only intermittently, he attended just a few of the sessions. His old friend and sometime mentor, Sherwood Anderson, later wrote, “Bill Faulkner arrived and got drunk. From time to time he appeared, got drunk again immediately, & disappeared. He kept asking everyone for drinks. If they didn’t give him any, he drank his own.” By the time for departure, Faulkner was glad to accept dramatist Paul Green’s offer of a ride to New York. This was the beginning of a journey by car and coastal steamer that would add to the lore of Faulkner’s drinking exploits before his circuitous return to Mississippi. Memories of these events were still green in Charlottesville in 1955. One of the journalists who wrote at length about the Southern Writers’ Conference was Emily Clark, and now it was her bequest that would be the linchpin for the return of its most spectacular participant.

Fred and I wrote to more than a dozen prominent writers, but we had very little money to offer, and some, such as Edmund Wilson and J.D. Salinger, said that they did not do that sort of thing. Some were doing it elsewhere. Others did not reply. When a friend of the English Department mentioned the plan to Jill Faulkner Summers, she said, “I think Pappy might be interested in that.” When Fred wrote to him in April of 1955, he indicated his interest and supplied a short list of his needs, including “a place to live and a servant to clean it.” When Fred and Floyd Stovall, our chairman, drove out to see him in April at Fox Haven Farm, where Jill and her husband Paul were living, Stovall said with some embarrassment that he doubted if they could raise $2,000. “Don’t worry about money,” Faulkner replied, “All I need is enough to buy a little whiskey and tobacco.” He agreed to come in the late winter and early spring.

The three of us on the Balch Commitee were delighted, and Floyd moved quickly. He urged the appointment to President Colgate W. Darden, a tall spare aristocrat, former governor of the state and a member of the DuPont family by marriage. “It would add prestige to the university,” Floyd said in summing up.

“The University of Virginia,” said Darden, “has sufficient prestige without William Faulkner.”

Floyd thought that Darden had obviously heard about Faulkner’s last appearance at the university. “I feel sure nothing like that will happen again,” he said reassuringly, and the president agreed to recommend his appointment as writer-in-residence for the second semester of 1956-1957.

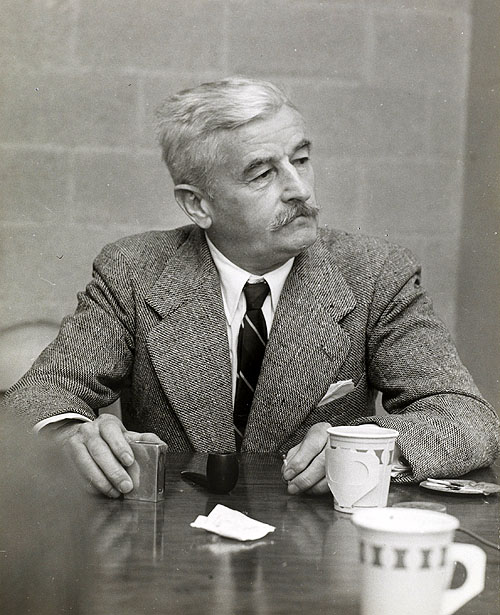

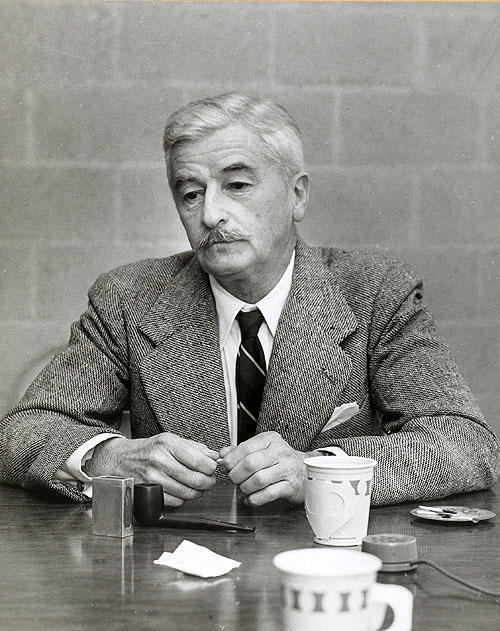

In January I glimpsed him for a moment from the other end of the long, dimly-lit corridor when he made a brief visit to the fifth floor of New Cabell Hall. A small man, severely erect, he moved slowly, turning into Fred’s office and out of my sight. On February 15th he strolled the Lawn in tweed suit and overcoat and Tyrolean hat, casually trim and elegant. After a press conference in Cabell Hall with the journalists and photographers who had trailed him along the Lawn, he met with students and visitors in Fred’s graduate course in American fiction. The session began with questions about The Sound and the Fury. He answered slowly and carefully in his light, soft voice. Then he would look down at the desk, idly turning over a matchbox housed in a metal holder decorated with RAF wings. His calm belied his feelings. “I’m terrified at first,” he would say later, “because I’m afraid it won’t move.” But it did, and the hour passed quickly. He was more relaxed at its end and in a session with reporters. When one asked why he accepted the invitation, he answered, “It was because I like your country. I like Virginia and I like Virginians. Because Virginians are all snobs, and I like snobs. A snob has to spend so much time being a snob that he has little left to meddle with you, and so it’s very plesant here.”

Enthusiastic admirers of his work as Fred and I were, we formed a kind of silent cheering section. After his accepting this gambit, we were anxious that it should succeed. I had heard a number of authors’ question-and-answer sessions, but his were different, and they were reflections of both his mind and personality. He was articulate but not voluble, and he could tolerate silence as few people could. He had submitted to many interviews, and over the years he had developed a number of formulaic answers, often wry and funny, and often conveying the flash and brilliance of epigrams. But he also had a spontaneous phrase-making gift. Though he looked attentively at questioners, I had the sense of a distance which he imposed between himself and the rest of us. This appearance had been an unparalleled experience for me and Fred too. When I returned to my office after meeting another class, Fred stuck his head in my door. “I’ll go get Mr. Faulkner and we’ll have coffee in my office,” he said. Before I could compose myself, Mr. Faulkner walked in.

He had an extraordinary presence. As I thought about it later, I realized that he radiated power. It was the kind of effect attributed to great tenors and matadors. Here this perception came from a number of things: from knowing I was with the man who had created so many works of art and who had such a profusion of gifts, from his aura of calm and silence, and from knowing how withdrawn and sometimes irascible he was said to be. When Fred introduced me and Mr. Faulkner extended his hand, it was not a handshake but a handclasp, the hard firm grip of a man used to exerting pressure, as in training horses and grasping hand tools. He spoke softly and casually. “Morning, Gin’ral,” he said.

He appeared perfectly relaxed in Fred’s large, cream-colored office, waiting quietly while the steaming Nescafe cooled, lighting a pipeful of his strong, rich-smelling tobacco, a blend so distinctive that you could enter a room and recognize that he had been there. As we sipped, he answered questions slowly and politely, but he obviously felt no need to initiate conversation for the sake of any amenities. He had been cordial, but when he left, walking slowly down the hall, head up, eyes straight ahead, Fred and I sat down as we would have after exercise that had claimed all our attention. Then Fred apologetically explained Faulkner’s odd greeting to me. Remembering his stories about World War I, and trying to make conversation that might interest him, Fred said that he and I had both flown in World War II. When Faulkner had expressed quiet interest, Fred had said, out of a mixture of nervousness and attempted humor, “I’ll go get General Blotner and we’ll have some coffee.” So the strange greeting had been an attempt to use local informal names. He did not employ it again, and soon he was calling us by our first names. We had enjoyed being with him, but it would be some time before we would be easy in his company.

Relatively few students took advantage of the office hours he offered to hold. “I sat there,” he said later, “and answered questions that could have been answered by a veterinarian or a priest.” Our colleagues kept up a steady stream of requests for him to appear in their classes, usually when they had assigned his fiction. As the junior member of the committee, I helped Fred in setting up the schedule and escorting him to class. When Floyd Stovall had written him in November, he had offered the department as a barrier against engagements beyond his duties, and Faulkner had gratefully accepted. It fell to Fred and me to do most of the shielding. We did so gladly, with the sense of intimacy it gradually helped to produce. Only later would we realize this would not endear us to some, including a few of our colleagues, but we didn’t care. This assignment was worth any amount of resentment. Only gradually would we recognize what a stroke of good fortune ours had been.

It occurred to us that our duties included an obligation to others besides the writer-in-residence. There were the students and teachers who would come after us and would not have the chance to ask the author of The Sound and the Fury and Absalom, Absalom! about his work. One day Fred and I resolved that after time spent with him we would write down what he said. But when we compared our recollections, we realized that this wouldn’t work. We couldn’t be his friend, but secretly recording what he said when he had thought he was talking casually. Only a few of his remarks at universities had been recorded, and others which had been misquoted or quoted out of context had caused misunderstanding and hurt feelings. There was one thing we could do. Fred suggested to him recording all the sessions. He readily agreed, and so one of us would carry a bulky tape recorder to class. That year Fred and I wore raincoats, and this sight of two average-sized men flanking a smaller one and carrying an object in a case reminded some of sinister characters in adventure movies. When one observer mentioned us to Faulkner, he replied, “They’re doing pretty well. Next month I’m going to teach them to fetch and carry.”

There was no telling when or how that sharp wit would flash out. And he provoked humor in others as well, though now it was good-natured rather than acerbic, as it had been many years before when envious locals had called him “Count No ’Count.” One of my students was a talented caricaturist. Al Carlson sketched him as long-nosed and spindly, cuffs over his knuckles, a book under his arm, one hand resting on a broken column as he looked smiling ahead. When the editor handed him his copy of The Virginia Spectator, I watched the subject, himself a talented caricaturist, take it and slowly inspect the cover. His face flushed with soundless laughter that grew until he was overcome with the paroxysms of coughing of the inveterate pipe smoker. There were other symptoms of the growing attitude that semester toward the writer-in-residence, one of pride and affection. What he had called snobbery in the first press conference had translated into respect for his privacy, and pride at the presence of a world-class artist on the Grounds of the University of Virginia.

Because Fred’s duties as editor of College English placed added demands on his time, he tended to have less of Mr. Faulkner’s society than I did. Some mornings he might stop in at my office rather than his own and sit there while he checked his morning mail. Occasionally he would surprise me with a comment. He had told Professor Atcheson Hench that his mail seemed initially to come mostly from old ladies criticizing his remarks that Virginians were snobs. He could never tell what subject they might broach. One morning he opened a letter, read it slowly, and then refolded it. “This woman says how she likes my work and then tells me what a hard time she’s having,” he said. “That means she’ll let me give her some money.” He deposited the letter in the wastebasket. He unfolded his Times and settled his dark-horn-rimmed glasses more firmly on his nose. I turned back to my preparations for class.

His class sessions and occasional readings from his work were interrupted in March by a two-week visit to Greece for the State Department to coincide with a performance of his Requiem for a Nun. His busy schedule was crowned by his reception of the Silver Medal of the Athens Academy. But this triumph came at a cost. The combination of fatigue, celebration, and his pattern of retreat from crowds precipitated a drinking cycle. Leaving behind him a trail of lost objects, he was back in Virginia in early April, in the hospital. Before long, however, he had recuperated enough to resume riding with friends, aiming to condition himself and take jumping instruction for fox hunting with the Keswick and Farmington Hunts.

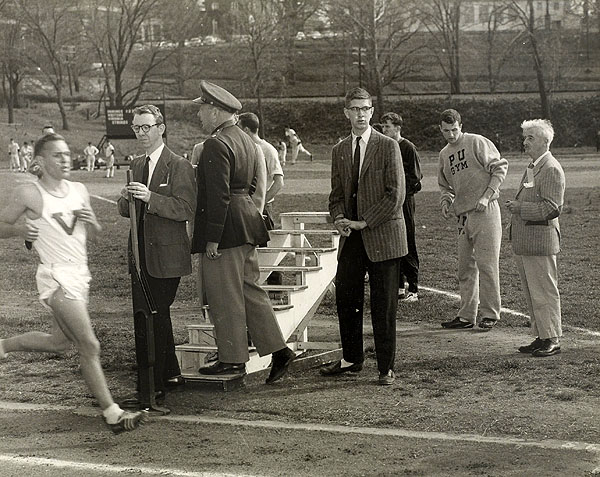

This was not an activity I had the skill or time to share with him, but fortunately there was another one. For a few years I had been helping to judge places in track meets or take times with a stopwatch, in return for which I received two seasons’ football tickets. With the approval of our supervisor, anatomist James Kindred, Faulkner joined me at the finish line of the 440-yard race. Our job was to pursue the first three finishers to get their names accurately. I should have known better by now than to think my fellow judge could escape observation and blend into the slim crowd in his khaki pants, linen jacket, and old Panama hat. Most of the athletes appeared not to know who this official was who walked after them rapidly at races’ ends asking, “Young man, young man, what’s your name?” One race, however, was different. The mile relay had just been won with a brilliant sprint by the visitors’ anchor man. A moment later, one of the runners walked up to us, his face flushed, and his chest heaving. “Sir,” he gasped, “in our class” – he struggled for breath – “we’ve just been reading your book.” He held out a copy of Light in August. “Would you please autograph it for me?” I recognized the visitors’ anchor man in the relay. Faulkner smiled and signed it. The winner thanked him profusely and walked away with an additional laurel from Charlottesville. As we were jotting down the first set of names, one of the officials who had met him earlier observed our progress.

“Well, Mr. Faulkner,” he said, “I see they’ve put you to work.”

“Yes,” he replied. “Blotner and I are workin’ for our letter. When we get it, we’re goin’ to put it on a sweater. I get to wear it on Sattidays.”

When it came to racing, he preferred the equine variety. He was riding often in spite of near-chronic back pain from injuries old and new and the inconvenience of having to depend occasionally on others for rides out to Grover Vandevender’s farm where he rode. We discussed the problem one morning over coffee in Fred’s office, which had become our Squadron Room. He said he had considered a motor scooter because a cycle might jar his back.

“We ought to get one of those belts for your back,” Fred said.

“Yes,” I added, “one of those wide black leather ones with red and blue stones on it.”

“We could letter ’Charlottesville’ on it,” Fred said.

“No,” Mr. Faulkner said, “we should put on it, ’Department of English.’”

The ambience of his various appearances was unpredictable and sometimes anticlimactic, as at one event of a kind he would have shunned ordinarily. On Friday, April 12, John Dos Passos arrived to address the law school and the Jefferson Society. A large man, smiling and diffident, he talked afterward at a reception with undergraduates clustering around him. Then the circle broke as some of the students made way for this other guest come to congratulate the speaker. When they saw it was Faulkner, those closest fell silent to hear the exchange between the two novelists who – according to Faulkner at least – were among the five best contemporaries in their craft. Faulkner extended his hand, and Dos Passos, a good head and a half taller, grasped it.

“Hello, Dos,” said Faulkner.

“Hello, Bill,” said Dos Passos.

They exchanged casual pleasantries as the circle reformed at a respectful distance and a photographer recorded the meeting. Dos Passos did not give the impression of shyness Faulkner did, but neither was he voluble, and so the two frequently fell silent as they sipped their drinks. After a short but polite interval, Faulkner offered his hand again.

“Well, good night, Dos,” he said.

“Good night, Bill,” his old acquaintance responded genially, and as the ring closed once more, Faulkner set off on foot for home.

For his scheduled public appearances, however, he usually rose to the occasion, and he was anxious to give what he considered full value for his appointment and remained wary of drifting into a formulaic routine of classroom sessions. As the end of April neared, it was time, as he put it, to “put the show on the road.” Students and faculty at other Virginia institutions were anxious to hear him, and so we set off in my car on a beautiful afternoon for Mary Washington College, the university’s sister institution in Fredericksburg an hour away. Well-turned out, his hair white from the morning’s shower, he was in good form, Reading rapidly as usual, from “Spotted Horses,” he held the attention of the young ladies of Mary Washington, who listened in a hush. They asked questions that were intelligent as well as respectful, and as if put on his mettle by their attractive presence, he was witty and responsive.

The American ambassador had recalled to me how after Faulkner discharged his last Nobel Prize obligation, he helped himself liberally from the drink tray as if he were saying, “School’s out.” Now, leaving Mary Washington, we walked through the sombre brick-walled cemetery where Confederate soldiers lay beneath dark weathered stones with fading letters. Any meditations on mortality they inspired may have increased his readiness for relaxation. We stopped by a meadow and uncorked the bottle of Jack Daniel’s he had brought along. It tasted fine out of paper cups with ice and a little water. Talking at random we looked out over the country. We had a second drink. When it was finished Mr. Faulkner said, “Let’s have another one.”

“Why don’t we go on,” Fred countered, “and find a restaurant where we can have one while we’re waiting for dinner?”

“I don’t see why we can’t finish the bottle here,” said Mr. Faulkner, with what sounded to me like the slightest edge to his voice.

Fred and I exchanged fleeting wary glances. We were both bourbon fanciers but essentially moderate drinkers, and I think Fred may have shared my sudden vision of darkness falling on the meadow with none of us in best shape to drive the car. Thinking too of Yvonne and the children at home waiting for dinner, I said “Let’s have one more here and then go.” Fred poured the drinks, and we enjoyed them without further discussion. The Jack Daniel’s was tasting even better now, but we went on to find a restaurant that served moderately good steaks, and at last we returned home in the fragrant evening.

There were further occasions for relaxation that spring. Each of us on the Balch Committee and our wives had found occasions to invite the Faulkners for drinks. If William Faulkner tended to be withdrawn, his wife, Estelle, had always been outgoing and popular, so much so that Faulkner’s college friend and first literary agent, Ben Wasson, would recall her in her youth as “the Butterfly of the Delta.” Slim now almost to the point of emaciation, she dressed elegantly. She had long since mastered the traditional arts of the Southern belle. Graceful and animated, never at a loss for conversation, she charmed effortlessly. “Call me ’Stelle,’” she had said and made us feel perfectly natural when we did.

The Town, the second volume of the projected trilogy describing Faulkner’s fictional Snopes family, made its appearance, and he gave us our inscribed copies. In the warm sunlight of late May, he and Estelle entertained the whole English Department, the French doors of their graceful Georgian home on Rugby Road thrown open to the spacious flagstone terrace. By mid-June, with the last of his University obligations discharged, we were free to go on the first of several planned expeditions. One bright morning at 5:30 his gray Plymouth station wagon pulled up in front of our house, and I went out to join him, Paul Summers, and Estelle’s son, Malcolm Franklin, for a tour of the Seven Days’ battlefields, the scene of bloody Civil War fighting. We took turns driving, and then, as the day wore on, made our way from Malvern Hill to Petersburg and Amelia Courthouse. Paul had brought along one of his West Point textbooks, and we stopped frequently to orient ourselves. It became obvious that Mr. Faulkner knew the battles in considerable detail, far better than any of the rest of us. The day turned warm and sunny, and though we were solemn and inclined to silence in the midst of the stone testimonials to awful carnage there, the trip had been a memorable one.

That evening, the Faulkners gave a Squadron dinner on the terrace at Rugby Road. (We were acquiring our own memorabilia even though we had thus far obtained only a model of the RAF Sopwith Camel for him – the Chief – and not yet the TBF bomber for Fred or the Flying Fortress for me.) We savored Estelle’s giant shrimp curry, ate quail eggs, and drank champagne. After dessert we had coffee and brandy in the candle light. In a momentary pause in the conversation, the Chief spoke. “Lieutenants Gwynn and Blotner, front and center,” he said in an abrupt, clipped voice.

Fred and I rose, stepped forward together, and came to attention. He stood at attention too and made a short rapid speech about our work, then stopped as abruptly as he had begun. The surprise still lingering, we said “Thank you, sir,” saluted, performed an uncoordinated about-face, and resumed our places. Fred was then 41, six years my senior, but I think he must have felt a glow just as I did. By late June the Faulkners were gone, back home in Mississippi attending to Rowan Oak and the needs of his Greenfield Farm out in the country. Indoor as well as outdoor work kept him busy, and it would be five months before he and Estelle could return to Charlottesville.

When the Faulkners returned, they brought with them two paintings by his mother, Maud Falkner – now increasingly well known for her realistic "American Primitive" style – one for the Gwynns and one for us. Although the Chief rode and hunted and sailed his sloop at home, he found more diversion here in Virginia. As he had gone to Little League baseball games with me in the spring, now in November he was ready to sample University of Virginia football. “I like this,” he told me. “This is real amateur sport. At home they got a tame millionaire and he buys a team for them.” Before half-time began the producer of the game’s radio coverage asked me if I could persuade Mr. Faulkner to talk with “Bullet Bill” Dudley, a Virginia football “immortal,” who was doing the color portion of the broadcast. When he agreed and followed me up the crowded aisle, the effluvium of his farm trench coat was nearly overpowering as we entered the confines of the broadcast booth. Reading from the producer’s scrawled note, Bullet Bill declared, “it’s a real pleasure to have with us today Mr. William Faulkner, winner of the Mobile Prize for Literature.” The Laureate was increasingly a unique presence in Charlottesville.

In the spring he had begun talking about moving to Charlottesville permanently. He had broached the subject sitting in my office. “I was thinking that it might be good to have some connection with the university after I’m through being writer-in-residence – if they can still use me, that is.” Mr. Stovall and Fred and I determined that we would go to the administration again when he returned in February. It was not as if he did not have work of his own to do. He was now well into The Mansion, the volume that would complete the Snopes trilogy begun so long ago. In January he remained faithful to a schedule of office hours that saw him seated at his Cabell Hall desk from 10:30 until noon five days a week. When he had no callers, he would read his New York Times for a while, then take from his trench coat a thick roll of white copy paper. Soon anyone passing could hear his slow tapping on Floyd Stovall’s portable typewriter.

Fred and I had only gradually become accustomed to our unique situation. In our developing careers we had gradually come to teach American classics, the work of Hawthorne and Melville, Twain and James, and others in the canon. Then suddenly we had found ourselves teaching that of an artist whom many anthologists and literary historians were placing on a similar level. It was a heady experience, in part because, though he was far from voluble himself, he gave us leave to ask anything in the class sessions and obviously made an effort to answer conscientiously. Our unspoken part of the bargain was to respect his personal and professional privacy. When we talked as friends in the Squadron Room, we did not interpolate the kind of literary questions he had heard for years, and in class we had asked more than we had ever expected to do. One result was his unasked volunteering of information virtually fresh from his worktable. Greeting him one morning, I asked how he was feeling. Not only was he fine, he said, but “I even got back to work on my novel.” Another morning in mid-February found him even more ready to talk.

“Get any work done this morning?” Fred asked.

“Yes,” he replied, stirring his coffee. “I haven’t worked for so long that it’s fun again. I got back to that Memphis whorehouse in Sanctuary, Miss Reba’s. That’s where I am right now. Senator Snopes is in Memphis and the nephew is going to barber college and they’re trying to preserve his innocence.” This was the kind of story-telling he had done as a young aspirant in Greenwich Village, sitting shoeless on the floor among friends, his imagination still busy with his creations. When Fred asked if Eula Varner’s daughter had reappeared, he volunteered more. “No,” he said, “that’s the third-act curtain to the whole thing” and went on to describe the action on which the end of the plot turned.

It was exciting to be this close to the artist’s smithy, and he even gave us a sense of participation in some of his work. In February he wrote out a talk he had been invited to deliver to three societies on the Grounds of the University. The political atmosphere in Virginia provided a special element of drama. The governor had promulgated a doctrine of “massive resistance” to federal pressure for integration. It would have been politic for William Faulkner to avoid the subject, but when he brought his talk with him to Fred’s office at coffee time and asked us both to read it, we saw that he had instead met the issue head on. “A Word to Virginians” was an appeal to lead the whole South in educating the Negro. The other Southern states still looked to Virginia as a mother. They had ignored her counsel once before, to their grief, but now, he wrote, “Show us the way and lead us in it. I believe we will follow you.”

“How’s that?” he asked us. We had both read the pages quickly.

“Good,” I said, thrilled more, I believe, by his request that we read his work than by the carefully worded appeal itself.

A week before, Floyd Stovall had talked to President Darden about some permanent tie to the university for Mr. Faulkner. Darden responded that though he appreciated Faulkner’s contribution, he felt that other writers who came under the Balch program would feel that they too might achieve permanent connections with the university. Though this seemed a lame and transparent excuse to us, we felt that Faulkner’s speech must have convinced Darden that his position was right. And the closing of some public schools, extending through 1958-1959 showed that it had extensive support.

Though there were still nearly a dozen class appearances ahead before William Faulkner’s term as writer-in-residence was over, there was a sense for us of the end of things as spring came in. We still gathered for coffee each morning, the Chief sitting in the low camp chair Fred had stencilled “Balch Chair of American Literature.” Katherine Anne Porter had been chosen as the next writer-in-residence. “I guess we ought to get a pipe,” I said “and have it engraved ‘Emily Clark Balch Pipe of American Literaure.’ That would still be yours.” He chuckled soundlessly. If we needed evidence that some did not share our regret at his vacating the position, I had heard it a few days earlier from another member of the Balch Committee, Fredson Bowers, who seemed likely to succeed Floyd Stovall as department chairman.

“Did ‘Pappy’ get over the idea that he was going to be the permanent writer-in-residence?” he asked me, with a broad grin. I replied that he had never seriously entertained that idea, and more than once he had asked me to tell him if he stopped being effective in the job.

Sometimes now his remarks would take on a valedictory tone, and we began a round of Squadron dinners, for in late May the Faulkners would return to Mississippi for the summer. Not long after that the Gwynns would be leaving as Fred took up the chair of the English department at Trinity College in Connecticut. Then, in August my wife and I would be departing for a Fulbright Lectureship at the University of Copenhagen. But these dinners were festive occasions. Knowing Mr. Faulkner’s taste for French cuisine, Yvonne served beef bourguignon, with baba au rhum for dessert. As he put down his spoon he asked, “What time’s breakfast, Miss Yvonne?”

He fulfilled his last public sessions and continued work at home on The Mansion. Earlier he had told Fred and me that he wanted us to see his new book. Because I had thought this just a polite remark, I was totally surprised when he arrived at our door one afternoon and handed me a manila portfolio.

“Here,” he said brusquely, “you can read this.” A glance inside showed me that it was a ribbon typescript, not just a carbon copy. It was the first third of his new novel, he said.

“You have another copy at home, don’t you?” I asked anxiously.

“No,” he said abruptly.

After he had left, I showed Yvonne what he had given me. She was aghast. “You don’t mean you expect to keep that overnight in a house with three little girls with crayons?” I read it that night, put it on top of our highest bookcase, and returned it to him the next day at cocktail time.

Even though the time was short, Floyd Stovall decided on one more try and walked up the Lawn to the president’s pavilion. “Mr. Darden,” he said, “I’d like to propose, with the concurrence of the English Department, that Mr. Faulkner be made an honorary lecturer in American literature to keep up his connection with the university.”

“There are no honorary positions at the University of Virginia,” was the reply. Colgate W. Darden had kept his no-hitter going.

There were, however, some tangible mementos. One night as the Faulkners sat in their Rugby Road living room, there was a knock on the door. Faulkner opened it and found no one there, but on the steps was a large package containing a silver tray from the Seven Society, an anonymous group of the university’s most distinguished sons. It was engraved to him in tribute to his contribution to the life of the university.

Our Fulbright year of 1958-59 passed rapidly with my teaching at the University of Copenhagen, lecturing elsewhere, and traveling strenuously in the summer through the Alps and as far as Rome before our return to Charlottesville in August. The Faulkners were back as the gold of October gave way to dappled November. Back in time for the Blessing of the Hounds, he was riding now with not just one hunt but with two, togged out in derby, stock and shining boots. But he was not neglecting his vocation for his avocation. He had finished his work on The Mansion, and on November 13 of 1959 it was published. Reading something he had written recently, I never knew when I would experience the shock of recognition. Sitting in Fred Gwynn’s office during those coffee and hangar-flying sessions, we had told war stories. Fred had said little about flying a TBF off a carrier in the Pacific, but I had told about the end of my brief career as a bombardier until we were shot down over Cologne, and about watching helplessly as green target flares drifted right over Stalag Luft XIII D when the RAF came over to bomb one of Germany’s largest marshalling yards. When I read Chapter Thirteen of The Mansion, I sat straight up in my chair. “I enjoyed that part about Chick’s experience in Germany,” I told the author later.

“I used your story about being bombed in POW camp,” he said with a smile. “I lifted that right from what you told me.”

There were other items that drew on our experiences. Fred and I had edited the Chief’s class conferences, and 36 of them would be published that year as Faulkner in the University. Saxe Commins at Random House had opposed the project for fear it would be thought Faulkner’s last word on his work. But then it was agreed that the University Press of Virginia would publish it, with the royalties to be split evenly among the three of us. We also made the joint resolve that they would always be spent on Jack Daniel’s.

Faulkner’s Virginia connection was signalized in two other ways as well. Linton Massey had suggested to University Librarian John C. Wyllie that some connection be found for Faulkner. Wyllie cautiously agreed, and in early January he released the news that William Faulkner would become consultant on contemporary literature to the Alderman Library. Very shortly thereafter he had a call from President Darden asking where he got the authority to add people to his staff and payroll that way. Tough-minded John Wyllie had a ready response. “There’s no money involved at all.” Faulkner would have a study with a desk, a chair, and a typewriter. “He’ll have access to anything in the library, but nobody will have access to him.” This time Darden made no rejoinder.

Buying land was a different kind of commitment. Hedda Hopper had reported from Hollywood that Rowan Oak was for sale, with a room reserved for Faulkner’s permanent use. Three days later the Associated Press followed this fanciful account with the word that the Faulkners had bought a home on Rugby Road in Charlotttesville and would move into their handsome Georgian brick house in August. He might never be able bring himself to sell Rowan Oak, but he intended to spend as much time living in Virginia as his tax situation would permit.