Introduction and Contexts

- Faulkner At Virginia: Introduction

- Faulkner in the Late 1950s

- The US in the Late 1950s

- Virginia in the Late 1950s

Virginia in the Late 1950s

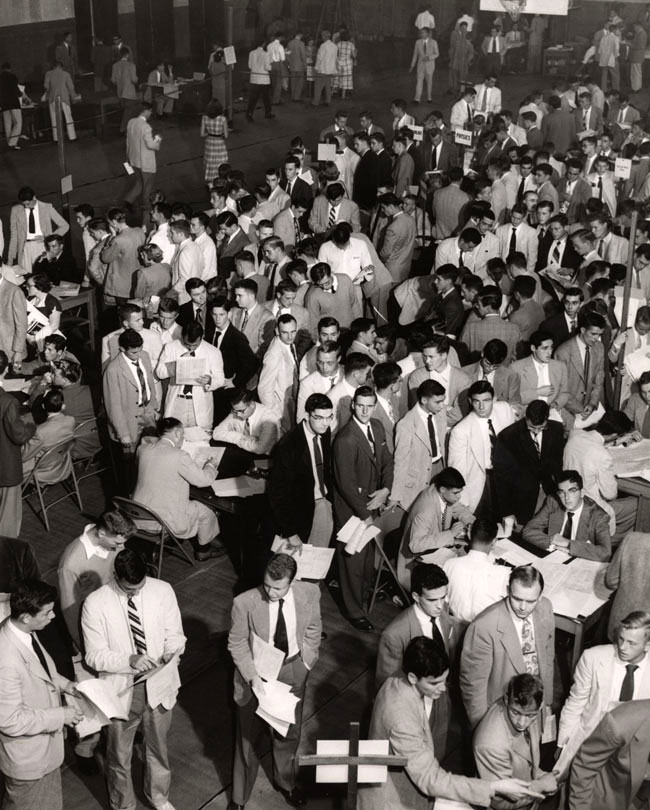

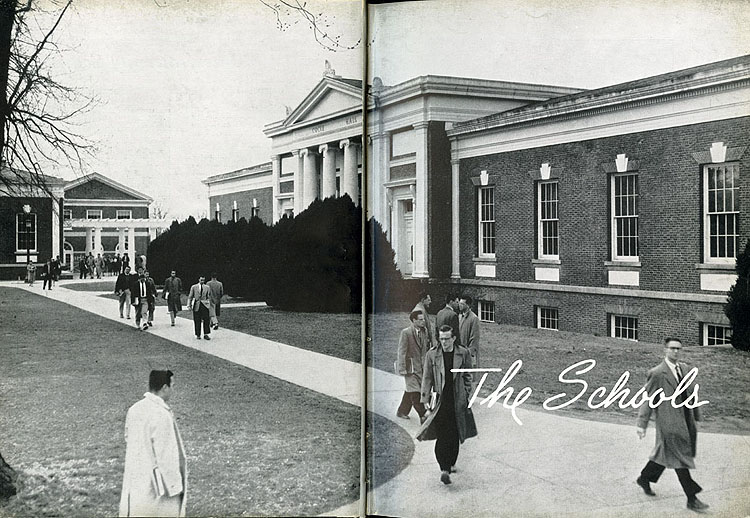

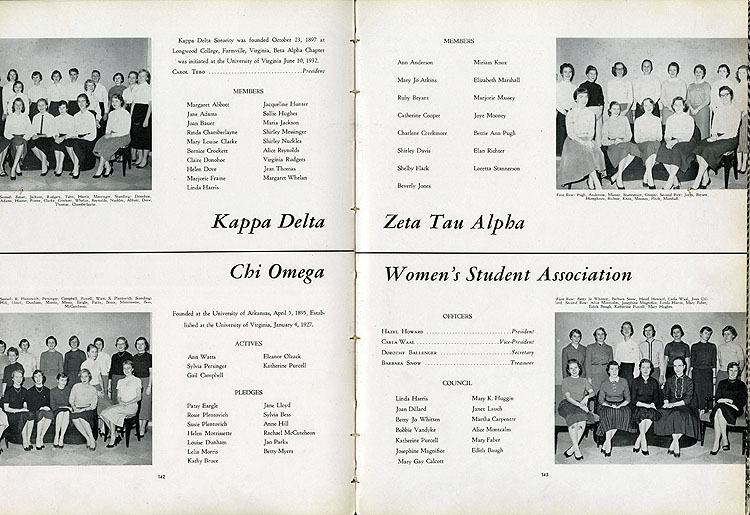

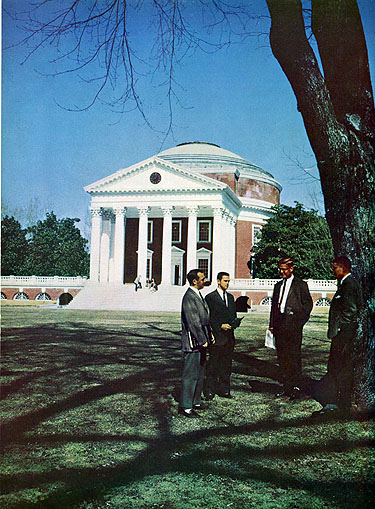

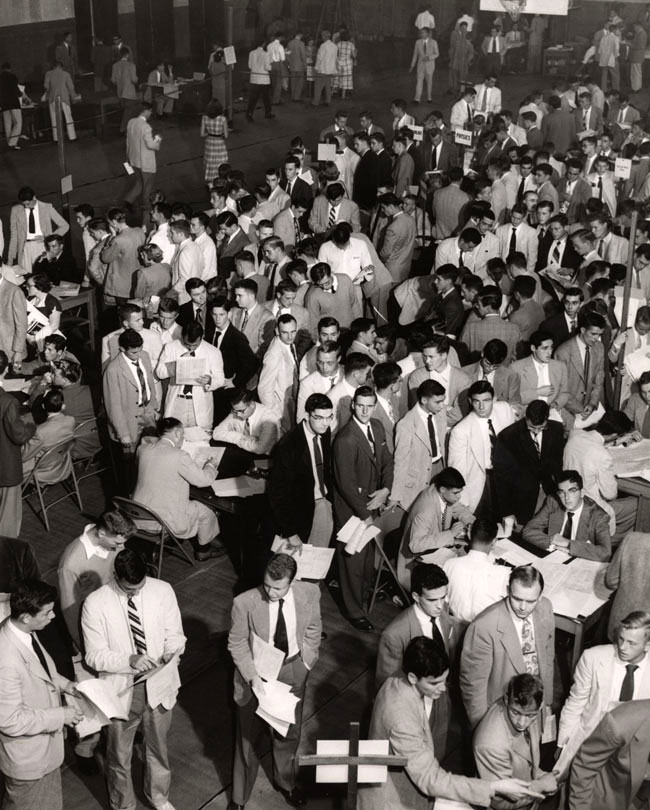

In February 1957, when William Faulkner arrived in Charlottesville to occupy his position as Virginia’s first

Writer-in-Residence, “Mr. Jefferson’s University” was 132 years old. Its first students matriculated

in March 1825: 123 undergraduates, all white males. There were almost five thousand UVA students by the 1956-1957 academic year,

but they were still mostly white and male. The Nursing School’s students were all female, the Education School was

largely female, and there were a few women students in the graduate Schools of Law, Medicine and Arts & Sciences, but

officially there were no women students in the College of Arts & Sciences until 1969, and the College was not fully

co-educational until the Class of 1976 arrived in 1972. There actually are a few women pictured among the college students in the

1957 and 1958 editions of Corks and Curls, the school yearbook, but they might have been daughters of faculty members;

during those years Mary Washington College, in Fredericksburg, was officially designated the state’s school for women.

(When Faulkner traveled there to speak in April 1957 he would still have been considered “in-residence” at

UVA.) A large number of the questions from Faulkner’s UVA audiences come from women; in May 1957 he met with a group

identified as “Wives of Law School Students,” and “wives” were explicitly invited to his

session with the English Department faculty the same month, but since women only made up about 3% of the total student body, it is

not clear who the women were whose voices you can hear during the other sessions, especially the classroom sessions. Several were

certainly graduate students in English or Education (four are identified by name in his 6 May 1958 session with

Stevenson’s English 32), many were interested residents of Charlottesville or Albemarle County, still others may have

been the wives of faculty members sitting in on classes when Faulkner was present. The presence of these women suggests the

environment at UVA wasn’t as “male” as it looks in the records. To my ear, at least, the

women’s voices we hear on the tapes don’t sound shy or hesitant about being part of the conversation

In February 1957, when William Faulkner arrived in Charlottesville to occupy his position as Virginia’s first

Writer-in-Residence, “Mr. Jefferson’s University” was 132 years old. Its first students matriculated

in March 1825: 123 undergraduates, all white males. There were almost five thousand UVA students by the 1956-1957 academic year,

but they were still mostly white and male. The Nursing School’s students were all female, the Education School was

largely female, and there were a few women students in the graduate Schools of Law, Medicine and Arts & Sciences, but

officially there were no women students in the College of Arts & Sciences until 1969, and the College was not fully

co-educational until the Class of 1976 arrived in 1972. There actually are a few women pictured among the college students in the

1957 and 1958 editions of Corks and Curls, the school yearbook, but they might have been daughters of faculty members;

during those years Mary Washington College, in Fredericksburg, was officially designated the state’s school for women.

(When Faulkner traveled there to speak in April 1957 he would still have been considered “in-residence” at

UVA.) A large number of the questions from Faulkner’s UVA audiences come from women; in May 1957 he met with a group

identified as “Wives of Law School Students,” and “wives” were explicitly invited to his

session with the English Department faculty the same month, but since women only made up about 3% of the total student body, it is

not clear who the women were whose voices you can hear during the other sessions, especially the classroom sessions. Several were

certainly graduate students in English or Education (four are identified by name in his 6 May 1958 session with

Stevenson’s English 32), many were interested residents of Charlottesville or Albemarle County, still others may have

been the wives of faculty members sitting in on classes when Faulkner was present. The presence of these women suggests the

environment at UVA wasn’t as “male” as it looks in the records. To my ear, at least, the

women’s voices we hear on the tapes don’t sound shy or hesitant about being part of the conversation

.

.

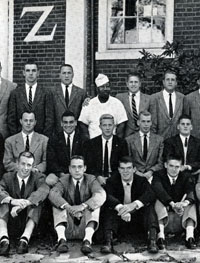

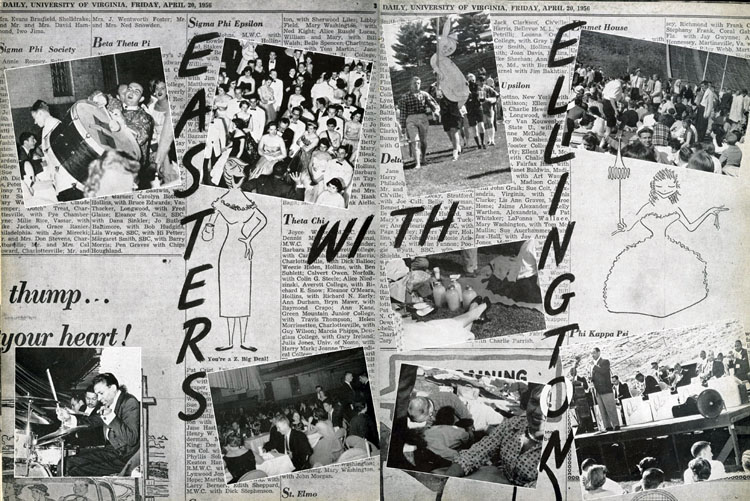

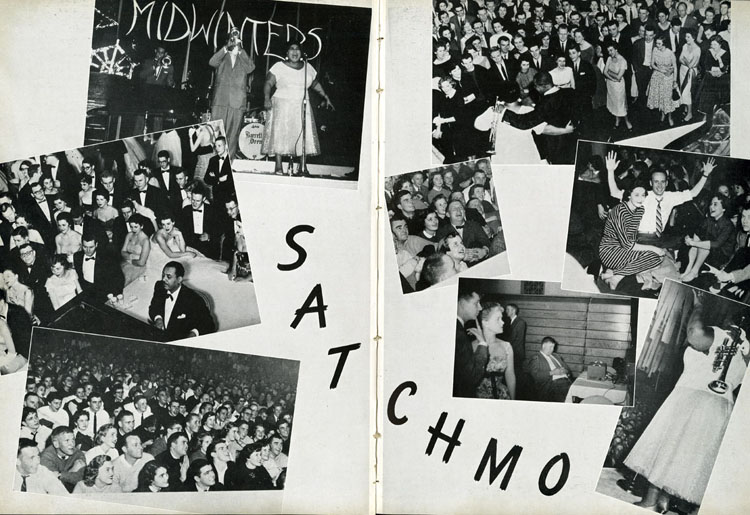

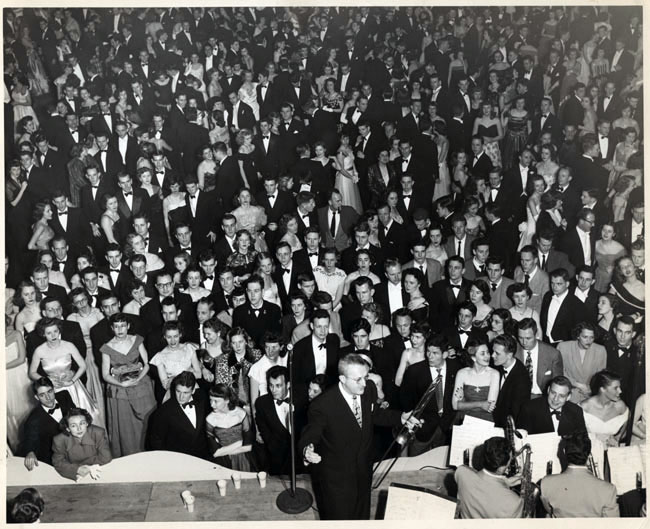

On the other hand, I don’t hear any recognizably “black” voices among the hundreds of people

who ask Faulkner questions, and it seems likely that there were no blacks in any of his audiences here (though one man on the

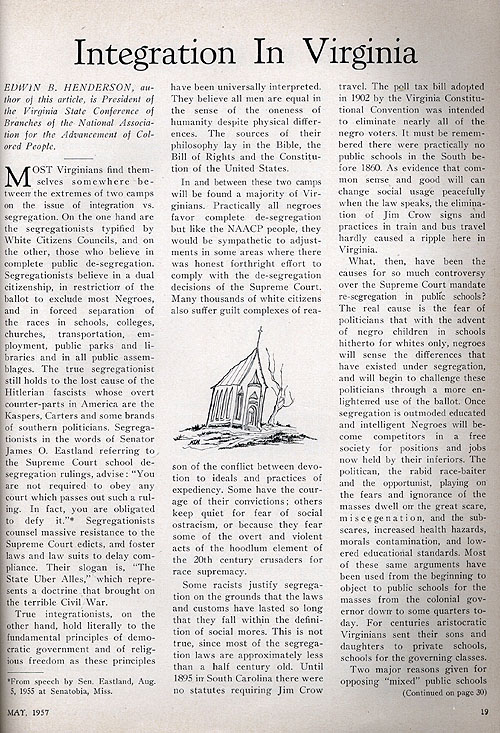

tapes identifies himself as an Indian national). Thanks to the series of legal battles fought by the NAACP in the courtroom in the

years leading up to the Supreme Court’s Brown v Board of Education decision, in the 1950s African American

students began attending UVA in very small numbers: a few in the Law School, in Education and in Engineering. I saw no sign of

these students in Corks and Curls from the years Faulkner was here; the only black faces in those yearbooks belong either

to the entertainers who came to town for the big weekends (Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, Louis Armstrong, among others) or to

the servants who worked for the fraternities (identified in the group photos simply by their first names). A May 1957 editorial in

the student newspaper, The Cavalier Daily, titled “Desegregation At The

University,” refers to “the Negro students [now] enrolled,” but adds that there has not been

any “social mixing between white and Negro” at UVA, “even when the two have attended dances together

in Memorial Gymnasium.”

On the other hand, I don’t hear any recognizably “black” voices among the hundreds of people

who ask Faulkner questions, and it seems likely that there were no blacks in any of his audiences here (though one man on the

tapes identifies himself as an Indian national). Thanks to the series of legal battles fought by the NAACP in the courtroom in the

years leading up to the Supreme Court’s Brown v Board of Education decision, in the 1950s African American

students began attending UVA in very small numbers: a few in the Law School, in Education and in Engineering. I saw no sign of

these students in Corks and Curls from the years Faulkner was here; the only black faces in those yearbooks belong either

to the entertainers who came to town for the big weekends (Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, Louis Armstrong, among others) or to

the servants who worked for the fraternities (identified in the group photos simply by their first names). A May 1957 editorial in

the student newspaper, The Cavalier Daily, titled “Desegregation At The

University,” refers to “the Negro students [now] enrolled,” but adds that there has not been

any “social mixing between white and Negro” at UVA, “even when the two have attended dances together

in Memorial Gymnasium.”

The “Supreme Court decision” comes up several times in Faulkner’s sessions at UVA, and no one

has to explain which decision is being referred to

The “Supreme Court decision” comes up several times in Faulkner’s sessions at UVA, and no one

has to explain which decision is being referred to

. You can hear the discussions that follow for yourself. I sense a good deal of anxiety in the room whenever this subject is

brought up, but very little openness to the possibility of social transformation. The large number of news articles about school

integration struggles throughout the South on the front pages of The Cavalier Daily between Fall 1956 and Spring 1958

(see below) suggests that white students were very interested in how traditional southern racial patterns might be

changing, but in those same issues there is no discussion of admitting black students to the College. Although UVA never seems to

be included in the category of “public schools,” a few voices were raised in the CD for school

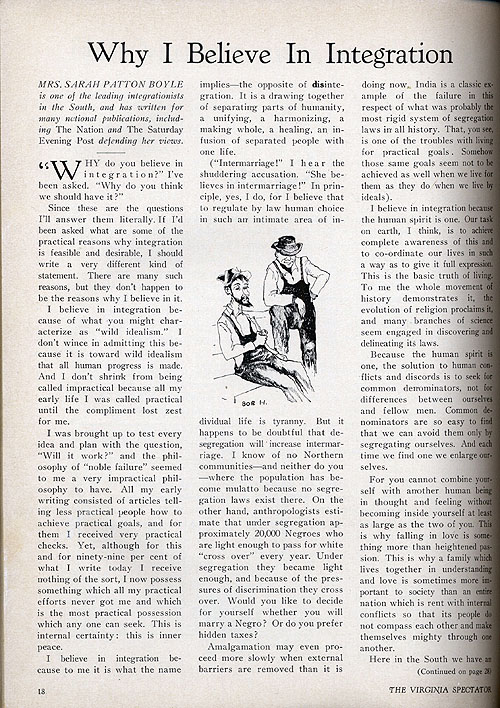

integration, belonging to some faculty members and one faculty wife (Sarah Boyle). The paper

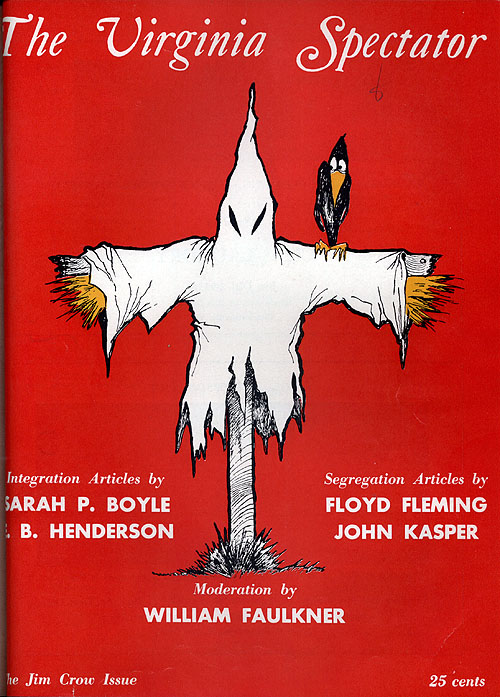

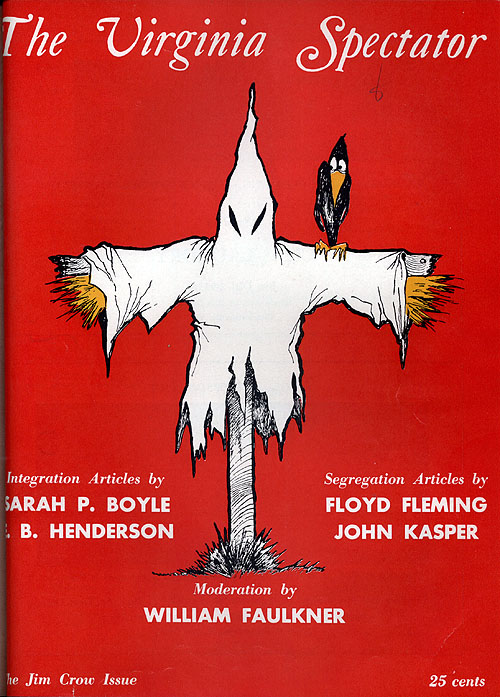

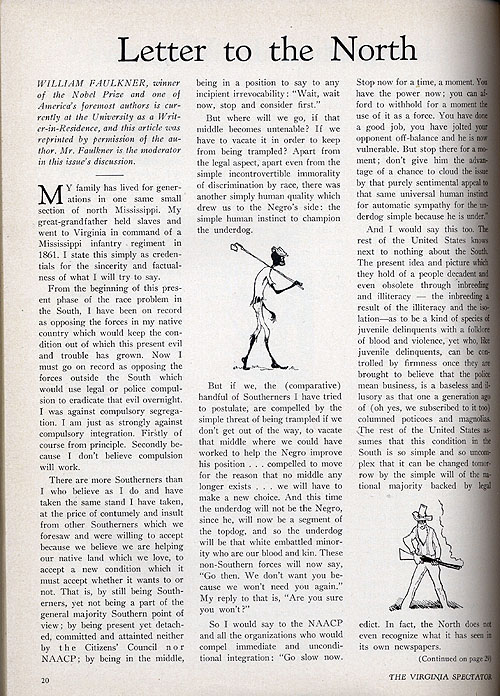

defended the “Jim Crow Issue” published in May 1958 by The Virginia Spectator; in the issue

this undergraduate monthly reprinted Faulkner’s Life magazine “Letter to the North” and

listed him as the “moderator” of the debate staged between four newly-written articles, two pro-segregation

and two pro-integration, none written by students (see below). Two weeks after the magazine appeared, Faulkner cited it

approvingly when he was asked to give examples of students resisting the pressure to conform

. You can hear the discussions that follow for yourself. I sense a good deal of anxiety in the room whenever this subject is

brought up, but very little openness to the possibility of social transformation. The large number of news articles about school

integration struggles throughout the South on the front pages of The Cavalier Daily between Fall 1956 and Spring 1958

(see below) suggests that white students were very interested in how traditional southern racial patterns might be

changing, but in those same issues there is no discussion of admitting black students to the College. Although UVA never seems to

be included in the category of “public schools,” a few voices were raised in the CD for school

integration, belonging to some faculty members and one faculty wife (Sarah Boyle). The paper

defended the “Jim Crow Issue” published in May 1958 by The Virginia Spectator; in the issue

this undergraduate monthly reprinted Faulkner’s Life magazine “Letter to the North” and

listed him as the “moderator” of the debate staged between four newly-written articles, two pro-segregation

and two pro-integration, none written by students (see below). Two weeks after the magazine appeared, Faulkner cited it

approvingly when he was asked to give examples of students resisting the pressure to conform

. But most articles in the newspaper suggest how deeply the student body was loyal to the racial status quo. When on 10 May 1957 the CD decided to respond to a challenge from the

Writer-in-Residence – “William Faulkner said yesterday, ‘I’d like to see more

undergraduates of this University express their opinions on topics of wide interest’” – by

conducting a “Poll on Integration,” students were given only two plans to choose between, and as the paper said, “Both plans have a common goal – prevention of

racial integration in the public schools.” The plan that called for delaying tactics defeated the one that advocated

vigorous defiance of the federal courts by two-to-one, but while one student wrote

“we must have complete integration” on his ballot, and another student

wrote the paper to complain that too few ballot boxes were available, no protests were registered about the narrow range

of “opinions” the poll reflected.

. But most articles in the newspaper suggest how deeply the student body was loyal to the racial status quo. When on 10 May 1957 the CD decided to respond to a challenge from the

Writer-in-Residence – “William Faulkner said yesterday, ‘I’d like to see more

undergraduates of this University express their opinions on topics of wide interest’” – by

conducting a “Poll on Integration,” students were given only two plans to choose between, and as the paper said, “Both plans have a common goal – prevention of

racial integration in the public schools.” The plan that called for delaying tactics defeated the one that advocated

vigorous defiance of the federal courts by two-to-one, but while one student wrote

“we must have complete integration” on his ballot, and another student

wrote the paper to complain that too few ballot boxes were available, no protests were registered about the narrow range

of “opinions” the poll reflected.

The “pressure to conform” to the mass was one of Faulkner's favorite topics in his sessions with UVA

audiences. To him it is perhaps the chief threat facing modern society

The “pressure to conform” to the mass was one of Faulkner's favorite topics in his sessions with UVA

audiences. To him it is perhaps the chief threat facing modern society

. He brought that concern with him to Virginia, but what he found at UVA probably only increased it. These were what Robert

Lowell called “the tranquilized Fifties,” and despite or because of Cold War fears about nuclear annihilation

there was a widespread national longing for what journalists were calling “normalcy.” Even so, the environment

at UVA in the late 1950s exalted conformity – though the students called it “tradition.” The suit

jackets and ties that students wore to all classes and public events as a kind of uniform were the outward and visible sign of a

community that was comfortable with the world that they found themselves in, and devoted to the rituals of the previous

generations of students. “Gentleman” was a word that resonated much more deeply with them than

“intellectual” or “artist.”

. He brought that concern with him to Virginia, but what he found at UVA probably only increased it. These were what Robert

Lowell called “the tranquilized Fifties,” and despite or because of Cold War fears about nuclear annihilation

there was a widespread national longing for what journalists were calling “normalcy.” Even so, the environment

at UVA in the late 1950s exalted conformity – though the students called it “tradition.” The suit

jackets and ties that students wore to all classes and public events as a kind of uniform were the outward and visible sign of a

community that was comfortable with the world that they found themselves in, and devoted to the rituals of the previous

generations of students. “Gentleman” was a word that resonated much more deeply with them than

“intellectual” or “artist.”

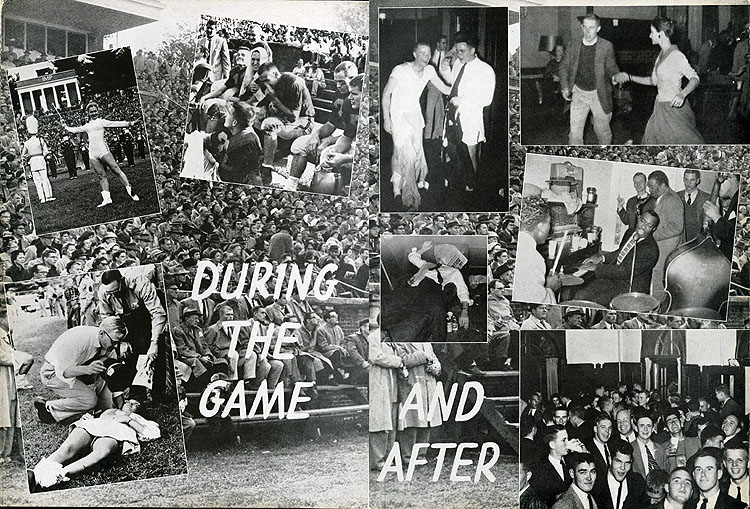

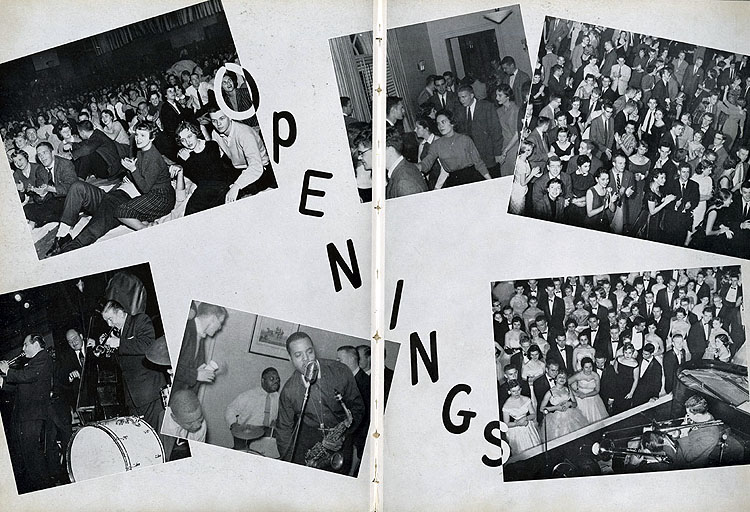

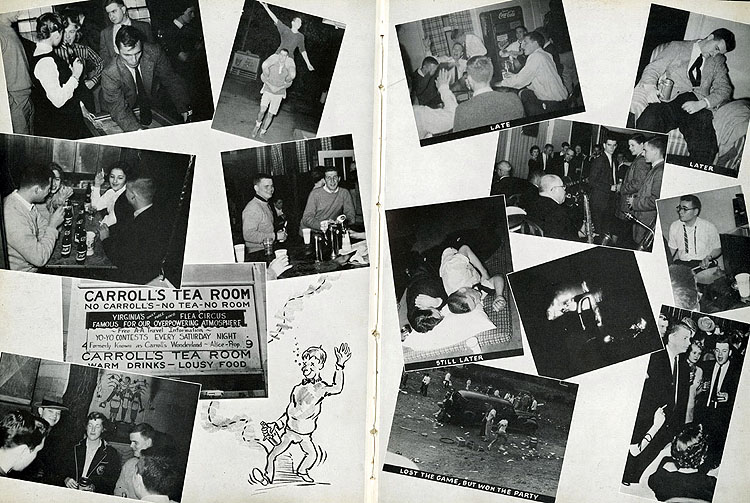

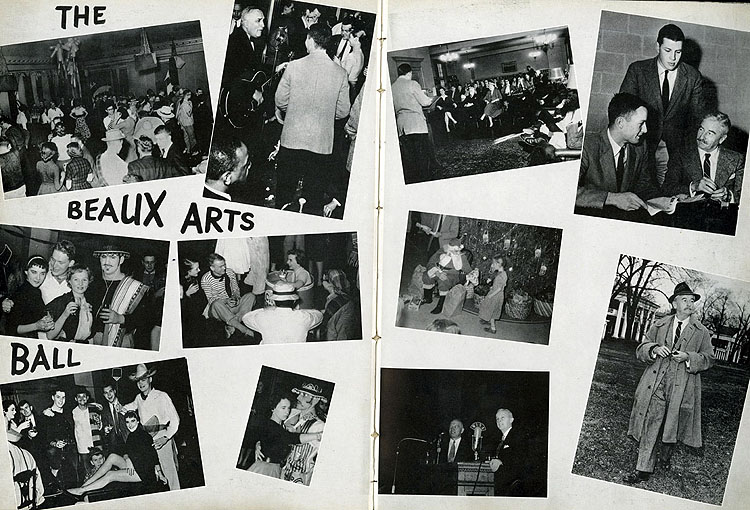

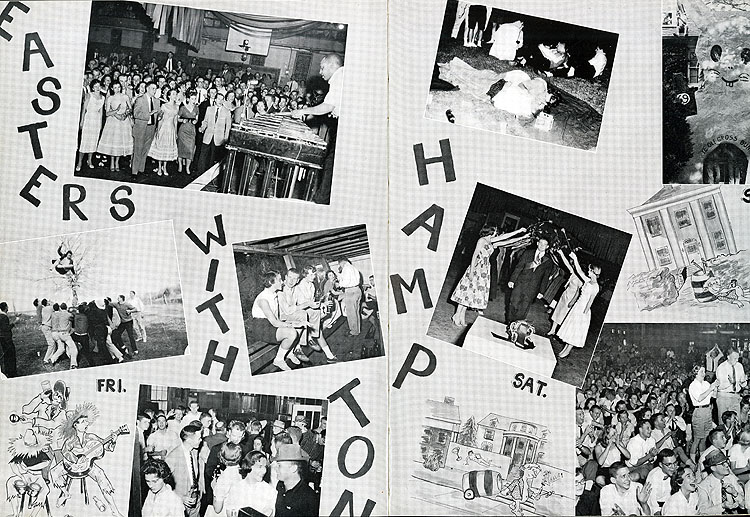

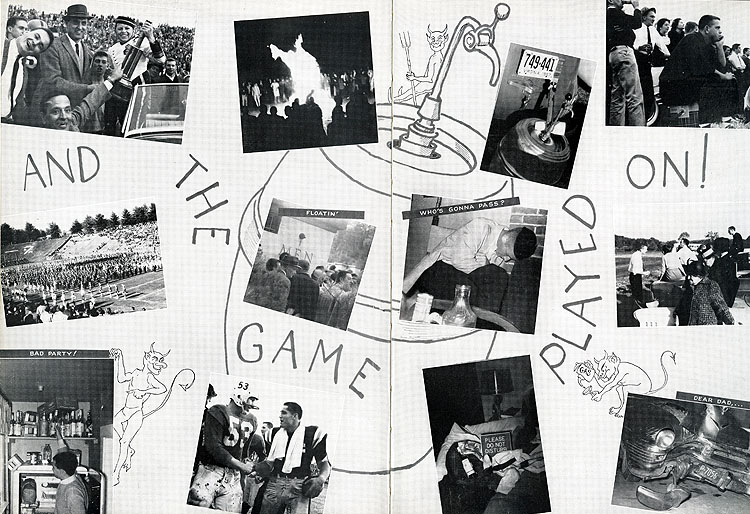

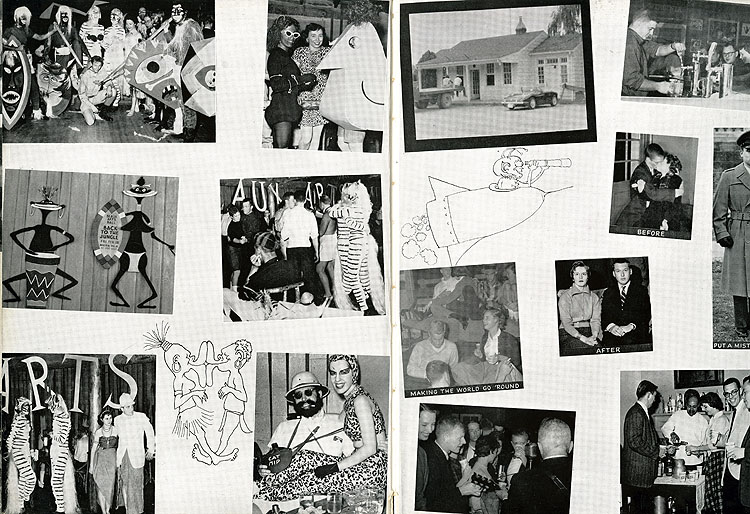

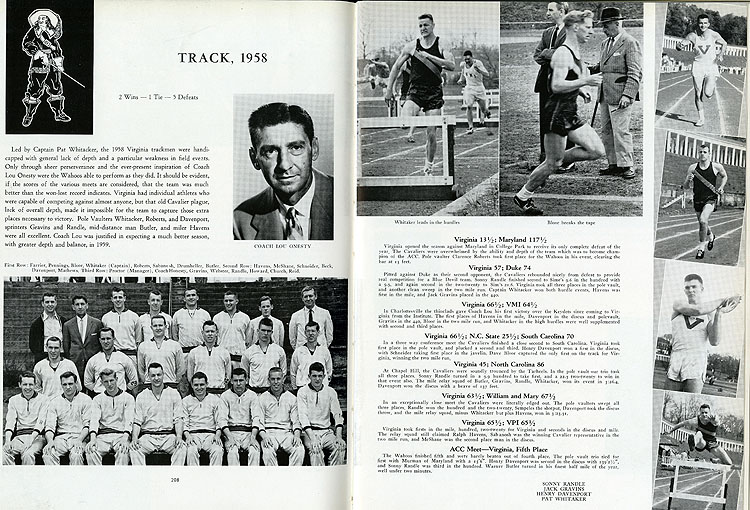

Faulkner’s picture appears twice in the 1957 Corks and Curls, in the “Features”

section (see below). Judging by the yearbook’s annual emphases, however, the chief features of student life at

UVA were fraternities, football games, and the three regularly occuring “big weekends” – Openings,

Mid-Winters, and Easters, supplemented by other annual events like the Beaux Arts Ball. For each of the three

“big” weekends The Cavalier Daily published expanded editions, allowing them to list all the women

(from other schools, of course) who would be attending, along with the names of their UVA dates. Again to judge by the

yearbook’s photos, music and alcohol were the main ingredients of these weekends. No one asked Faulkner during any of

his sessions about Gowan Stevens, the character in Sanctuary who has just graduated from Virginia and can’t

stop talking about how he’d “learned in a good school” how to drink, which turns out to mean how to

get drunk; if Faulkner’s interrogators were embarrassed to bring Gowan up, though, the yearbook seems to celebrate

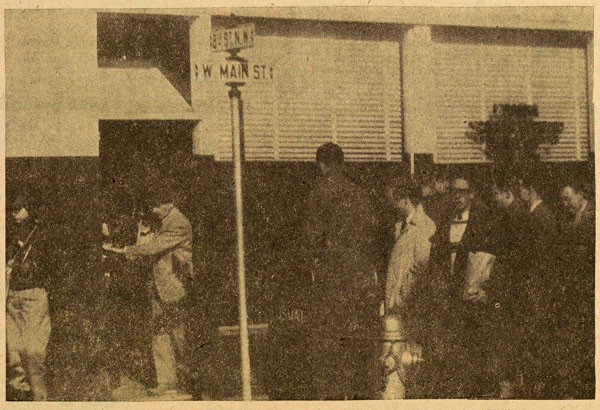

displays of drunkenness. This prevailing alcoholic culture makes it hard to know how to “read” the photograph

above left, published on the front page of The Cavalier Daily's “Mid-Winters

Issue,”which appeared the morning after Faulkner gave his speech exhorting Virginians to show the rest of the South the

way toward integration – a picture of the Writer-in-Residence coming out of the liquor store with a paper bag in his

hands. Is it an attempt to undercut his message by suggesting it came out of a bottle of booze? or does it imply (especially since

students would be stocking up their own bottles for the weekend) that Faulkner is “one of us”? (The photo was

taken by Ken Ringle, who discusses it in his essay on Faulkner at UVA; in the first issue

of the CD after the weekend, the paper ran an editorial about the speech,

expressing disappointment with Faulkner’s inadequacies as a speaker, but approving the way “Faulkner's

proposal [for improving Negro education] offers the compromise between the dogmatism of the North and the South on the

subject.”)

Faulkner’s picture appears twice in the 1957 Corks and Curls, in the “Features”

section (see below). Judging by the yearbook’s annual emphases, however, the chief features of student life at

UVA were fraternities, football games, and the three regularly occuring “big weekends” – Openings,

Mid-Winters, and Easters, supplemented by other annual events like the Beaux Arts Ball. For each of the three

“big” weekends The Cavalier Daily published expanded editions, allowing them to list all the women

(from other schools, of course) who would be attending, along with the names of their UVA dates. Again to judge by the

yearbook’s photos, music and alcohol were the main ingredients of these weekends. No one asked Faulkner during any of

his sessions about Gowan Stevens, the character in Sanctuary who has just graduated from Virginia and can’t

stop talking about how he’d “learned in a good school” how to drink, which turns out to mean how to

get drunk; if Faulkner’s interrogators were embarrassed to bring Gowan up, though, the yearbook seems to celebrate

displays of drunkenness. This prevailing alcoholic culture makes it hard to know how to “read” the photograph

above left, published on the front page of The Cavalier Daily's “Mid-Winters

Issue,”which appeared the morning after Faulkner gave his speech exhorting Virginians to show the rest of the South the

way toward integration – a picture of the Writer-in-Residence coming out of the liquor store with a paper bag in his

hands. Is it an attempt to undercut his message by suggesting it came out of a bottle of booze? or does it imply (especially since

students would be stocking up their own bottles for the weekend) that Faulkner is “one of us”? (The photo was

taken by Ken Ringle, who discusses it in his essay on Faulkner at UVA; in the first issue

of the CD after the weekend, the paper ran an editorial about the speech,

expressing disappointment with Faulkner’s inadequacies as a speaker, but approving the way “Faulkner's

proposal [for improving Negro education] offers the compromise between the dogmatism of the North and the South on the

subject.”)

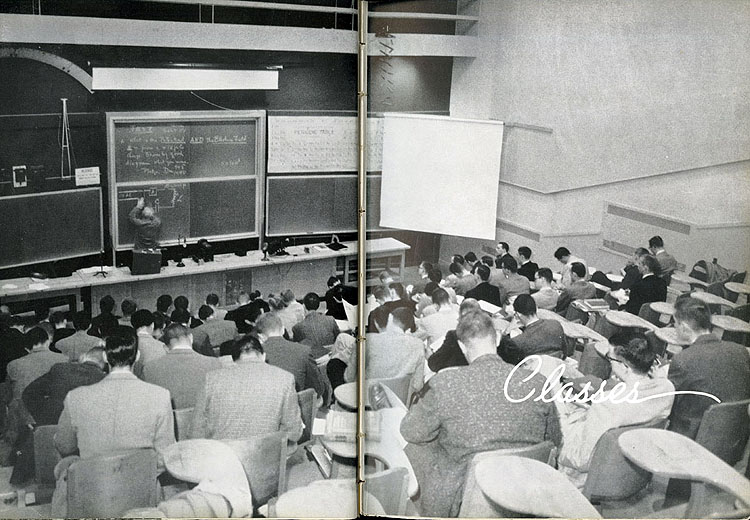

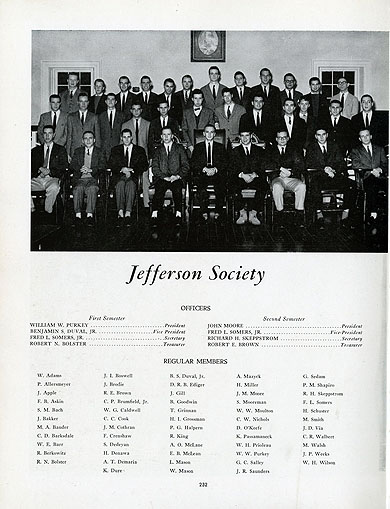

Although probably only about half of the people who ask Faulkner questions on the tapes were UVA students, the most common

setting for these sessions was an English Department class. In 1957 and 1958 the department’s faculty were also all

white and male, and as you can hear by their accents on the tapes, mostly from the South. (It was several years after

Faulkner’s residency that Fredson Bowers became departmental chair and launched an ambitious effort to re-make UVA

English by recruiting scholars nationally; by the time I arrived at UVA in 1974, I heard few southern accents at department

meetings.) Even senior faculty taught first-year composition and second-year introductory courses. The study of literature was

essentially as steeped in tradition as the mores of the undergraduates. During the 1956-1957 academic year the department offered

36 undergraduate and 24 graduate literature courses. Only two authors were studied separately – Chaucer and Shakespeare;

at the graduate level Fredson Bowers taught “Spenser and Milton” in addition to

“Shakespeare.” Only seven courses were dedicated to American literature, three for undergraduates, all taught

by Frederick Gwynn, and four for grad students taught by Floyd Stovall, the department’s most recognized Americanist and

departmental Chair during Faulkner’s tenure. There were also three courses taught by Edward McAleer in twentieth-century

writers – none at the graduate level. Most of Faulkner’s classroom sessions are with students in these groups

of classes and Joseph Blotner’s undergrad courses on “The Novel,” though he also answered questions

from students in both introductory and writing classes who had read one of his stories.

Although probably only about half of the people who ask Faulkner questions on the tapes were UVA students, the most common

setting for these sessions was an English Department class. In 1957 and 1958 the department’s faculty were also all

white and male, and as you can hear by their accents on the tapes, mostly from the South. (It was several years after

Faulkner’s residency that Fredson Bowers became departmental chair and launched an ambitious effort to re-make UVA

English by recruiting scholars nationally; by the time I arrived at UVA in 1974, I heard few southern accents at department

meetings.) Even senior faculty taught first-year composition and second-year introductory courses. The study of literature was

essentially as steeped in tradition as the mores of the undergraduates. During the 1956-1957 academic year the department offered

36 undergraduate and 24 graduate literature courses. Only two authors were studied separately – Chaucer and Shakespeare;

at the graduate level Fredson Bowers taught “Spenser and Milton” in addition to

“Shakespeare.” Only seven courses were dedicated to American literature, three for undergraduates, all taught

by Frederick Gwynn, and four for grad students taught by Floyd Stovall, the department’s most recognized Americanist and

departmental Chair during Faulkner’s tenure. There were also three courses taught by Edward McAleer in twentieth-century

writers – none at the graduate level. Most of Faulkner’s classroom sessions are with students in these groups

of classes and Joseph Blotner’s undergrad courses on “The Novel,” though he also answered questions

from students in both introductory and writing classes who had read one of his stories.

On the tapes you’ll hear a lot of questions about the meaning of specific symbols in specific texts. This focus was a

symptom of the times, not the place. In 1959, for example, Flannery O’Connor met with teachers and students at Wesleyan;

her report of the event suggests how in college classrooms across the U.S. in the Fifties the study of literature emphasized the

interpretation of symbols: “Week before last I went to Wesleyan and read A Good Man Is Hard To Find. After it I went to

one of the classes where I was asked questions. There were a couple of young teachers there and one of them, an earnest type,

started asking the questions. ‘Miss O’Connor,’ he said, ‘why was the Misfit’s

hat black?’ I said most countrymen in Georgia wore black hats. He looked pretty disappointed. Then he said,

‘Miss O’Connor, the Misfit represents Christ, does he not?’ He does not. He said, ‘what it

is the significance of the Misfit’s hat?’ I said it was to cover his head; and after that he left me alone.

Anyway, that’s what’s happening to the teaching of literature.”

*

Faulkner sometimes sounds equally tired of similar questions about his work

On the tapes you’ll hear a lot of questions about the meaning of specific symbols in specific texts. This focus was a

symptom of the times, not the place. In 1959, for example, Flannery O’Connor met with teachers and students at Wesleyan;

her report of the event suggests how in college classrooms across the U.S. in the Fifties the study of literature emphasized the

interpretation of symbols: “Week before last I went to Wesleyan and read A Good Man Is Hard To Find. After it I went to

one of the classes where I was asked questions. There were a couple of young teachers there and one of them, an earnest type,

started asking the questions. ‘Miss O’Connor,’ he said, ‘why was the Misfit’s

hat black?’ I said most countrymen in Georgia wore black hats. He looked pretty disappointed. Then he said,

‘Miss O’Connor, the Misfit represents Christ, does he not?’ He does not. He said, ‘what it

is the significance of the Misfit’s hat?’ I said it was to cover his head; and after that he left me alone.

Anyway, that’s what’s happening to the teaching of literature.”

*

Faulkner sometimes sounds equally tired of similar questions about his work

, though his answers, while often evasive, are always courteous.

, though his answers, while often evasive, are always courteous.

While UVA students may have studied literature in much the same way as students elsewhere in the country, in most respects the environment on the Grounds was very provincial. In some respects Faulkner and his voice fit right into this picture. At the beginning of his stay Faulkner announced that one of his goals in coming to Virginia was “to help create an atmosphere.” He didn’t elaborate, but at least one of the students who was here at the time, Gerald Cooper, believes that Faulkner’s presence made students more likely to realize that there was a larger world and other ways of thinking and acting about it and in it.

“The University in the Late Fifties,” by Ken Ringle (UVA ’61)

Images from Corks and Curls, the UVA yearbook —

Images from UVA Prints Collection, Alderman Library —

The “Jim Crow Issue” of Virginia Spectator (May 1957):

Images from the “Jim Crow Issue” —

Articles from the “Jim Crow Issue” —

- Up and Down from Slavery (issue introduction)

- Keynote (introduction to the essays (issue introduction)

- Why I Believe in Integration, by Sarah Patton Boyle

- Integration in Virginia, by Edwin B. Henderson

- Letter to the North, by William Faulkner

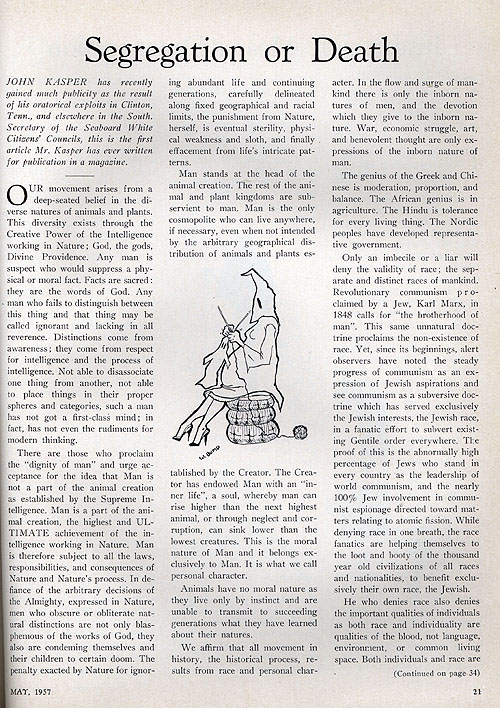

- Segregation or Death, by John Kasper

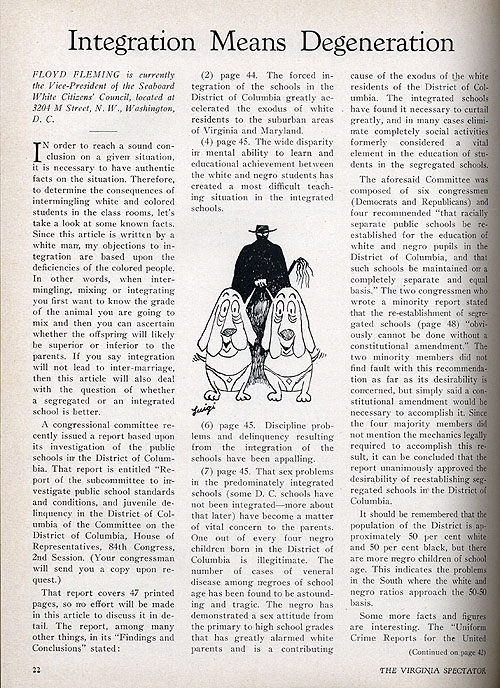

- Integration Means Degeneration, by Floyd Fleming

- Sutee, by Thomas Hawley (story)

- The Workout, by B. B. Schwartz (story)

- La Tour Abolie, by John H. Sacks (story)

- Crassingwick, by James McNally (poem)

Articles about integration (including women) from The Cavalier Daily —

- Legislature Passes Segregation Plan After Bitter Struggle (25 September 1956)

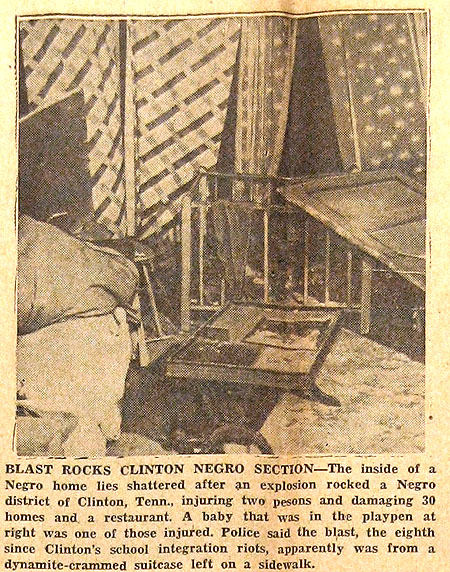

- Anti-Integration Blast Rocks Clinton Negroes (28 September 1956)

- Yale's Co-ed Panic (10 October 1956)

- Three Professors Argue for Integration (17 November 1956)

- Clinton Classroom Integrated Quietly (11 December 1956)

- Prominent Integration Leader Boyle Decries 'Cool' Motives Of Virginians (4 January 1957)

- Mrs. Boyle's Letter Called 'Paradoxical' (5 January 1957)

- Writer Hits Violence In Racial Issue (19 February 1957)

- Letter To The Editor [Clinton Bomb photo] (26 February 1957)

- Integration Leader Attacked By Whites (7 March 1957)

- High Court Refuses To Change Virginia Desegregation Rulings (26 March 1957)

- The Order To Desegregate (26 March 1957)

- Mistaken Invitation And A Damaged Reputation (16 April 1957)

- SC Examines Spectator/Council To Investigate 'Segregation' Issue (8 May 1958)

- Council Investigates Spectator (8 May 1957)

- Opinion Poll Next Week (10 May 1957)

- Cavalier Daily Will Conduct Poll On Integration (14 May 1957)

- Tomorrow's Poll (14 May 1957)

- Cavalier Daily Conducts Poll On Segregation (15 May 1957)

- Important Choice (15 May 1957)

- Sparse Voting Endorses Gray Plan (16 May 1957)

- Opinion Poll (16 May 1957)

- Letter to Editor [Opinion Poll] (17 May 1957)

- Law School Team Banned From Field (17 May 1957)

- Integration Report In Social Functions At U Given By Student Council (22 May 1957)

- Desegregation At The University (22 May 1957)

- Segregation: More Understanding Needed (17 September 1957)

- The Old States' Rights Question (24 September 1957)

- The Little Rock Fiasco (26 September 1957)

- Student Legal Forum Sponsors Discussion of Civil Rights (26 September 1957)

- The Female Equivalent (12 October 1957)

- Segregation Statement Issued by Copeley Hill (7 November 1957)

- Women, Wahoos and Words (12 February 1958)

- Darden Says Christianity Only Force That Can Combat Communist Threat (1 May 1958)

- Charlottesville Showdown (14 May 1958)

Below: "Registration and Orientation at Memorial Gymnasium," Ralph Thompson photo from UVA Prints Collection [Image Filename: prints01717; undated, but late 1950s]. Caption on back: "Students line up for courses at registration."

Below: Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, from Corks & Curls, the UVA yearbook (1957 edition, vol. 69, p. 85).

The Cavalier Daily 22 May 1957: 2

Desegregation at the University

Last year's Student Council drafted a statement setting forth their position regarding social integration of the white and Negro races in University-connected activities (See text of statement on Page 1). The document has just been released for publication.

From beginning to end, this Council paper exhibits calm judgement which makes it a refreshing change from much of what we hear relative to the problem of racial integration in the South today. Rather than try to write rules and regulations covering the situation, the Council calls for nothing more than wise discretion on the parts of all students.

We feel that the success or failure of race relations at the University now rests largely in the hands of Negro students enrolled. Desegregation has gone over smoothly here because it has not been rushed by the colored race and because it has not caused social mixing between white and Negro. Even when the two have attended dances together in Memorial Gymnasium, there has been not the slightest hint of trouble or violence.

Any attempt at exploiting this situation by either race will destroy this atmosphere of calm and good will and result in conflict which will bring both chaos and disgrace to the University. We hope that the same mature judgement and good sense will prevail in the future which we have witnessed in the past and that other colleges and universities will take note of the progress which this attitude has caused here. Both races can be justly proud of racial relations between students of this University.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

Below: Cover from the "Jim Crow Issue" of the Virginia Spectator monthly magazine (May 1957; vol. 118, no. 8).

The Cavalier Daily 8 May 1957: 2

Council Investigates Spectator

An important decision was made in Monday night's meeting of the Student Council. Four Councilmen have been assigned to investigate the forthcoming issue of the Virginia Spectator due on the stands Friday. The magazine will be devoted to a study of racial segregation. The Council decision to look into this matter is one which has taken courage and which reflects deep concern over the potentialities of such a magazine.

Five articles will be presented. John Kasper, arch-segregationist of Clinton, Tennessee, and Charlottesville notoriety, has written an argument in favor of separation entitled "Segregation or Death." This is the first piece written for publication by this person.

A second pro-segregation article, "Segregation Means Degeneration," has been submitted by Floyd Fleming, Vice-President of the Seaboard White Citizens Council on which Kasper is Executive Secretary.

Two authors have written pro-integration articles. Sarah Patton Boyle of Charlottesville has contributed "Why I Believe in Integration" and Virginia NAACP president Edwin B. Henderson has submitted "Integration in Virginia."

William Faulkner, noted author and University Writer-in-Residence, has written a "middle-of-the-road" stand which previously appeared in Life Magazine, "A Letter to the North." There is little doubt that this issue of the Spectator will receive wide attention and comment.

We say that the Council decision to investigate was courageous because another course of action (or inaction) was available to them. They could just as easily have ignored this matter and waited to see what reaction it would cause after the Spectator had gone on sale. In taking the more positive approach and looking into this magazine before it reaches the public, the Council not only risks charges of interfering with the free press (which they are in no way doing) but more important, they fore themselves into the position where they must publicly go on record either in favor of or opposed to publication of the issue. This is not an envious position but, as several Councilmen stated, one to which they are obligated by virtue of the office to which they were elected.

It is one thing to investigate and another to act. If the Student Council finds this magazine unacceptable to the University, what measures can they take against the Spectator Corporation? Two regulations seem to apply–one a Council bylaw and the other a University regulation. Section 5 of Bylaw IV states,

"All student organizations excepting the Honor Committee, the Judiciary Committee, and self-governing groups hold their power from the Student Council and are subject to the regulations of the Council."

University regulations as set forth in the University of Virginia Record specify, after referring to a list of approved publications, that:

"...students who wish to publish, distribute or sell any other publication must first obtain approval of the Student Council..."

(The reference to "other" publications would at first imply that the Council authority extended only to activities not included in the above-mentioned list of approved publications. But, authority over one such organization certainly implies authority over them all in a case such as this.)

We hope that there will be no need to use either of these rules against the Spectator. Presentation of this issue, if handled intelligently and maturely, can make the magazine a genuine contribution to the study of racial segregation and integration and a credit to the University. Anything short of this however, can make it a disaster. In this fact is found justification for the Council's choice to investigate. The handling of this matter calls for thought and good judgement on the parts of all persons concerned. We believe it will receive just this.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 10 May 1957: 2

Opinion Poll Next Week

William Faulkner said yesterday, "I'd like to see more undergraduates of this University express their opinions on topics of wide interest." In this short statement, Mr. Faulkner probably struck the principal failing of this student body. It gets back to the old problem of apathy, or whatever else one might wish to label it.

Today's Spectator marks somewhat of a departure from this silence and it has been the policy of this newspaper to comment on any and all such issues as they arise. What is missing however, is response from readers and members of the student body.

We hope to correct this on at least one problem–school segregation in Virginia–through a University-wide poll in one of next week's publications. The student body will be asked its opinion on the methods in which the state government is currently handling the school problem as it faces us today. If the response from this poll is as complete as was the one from last year's straw ballot on the Presidential election, a valuable service will have been done in showing how the younger people of this state react to what we believe is Virginia's gravest problem.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 15 May 1957: 2

Important Choice

Since May 17, 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the practice of school segregation by race was illegal, many plans have been proposed as solutions to the problem which has arisen. Among these many, two have received wide attention in Virginia–the Gray Plan and the Stanley Plan.

The first was approved in a statewide referendum of January 9, 1956 and the second became state law when enacted by the Virginia General Assembly last summer.

Gray Plan

The Gray Plan was submitted to Governor Stanley in the fall of 1955 by the Commission on Public Education, headed by State Senator Garland Gray. It was designed to place barriers in the path of school integration but, at the same time, to allow some degree of desegregation in areas where it was felt that such a plan would be acceptable to parents of school children.

In cases where children would have been forced into integrated schools against their wills, however, a financial grant would have been provided to be used toward the private school education of these students.

The plan was originally accepted by the Governor Stanley who then submitted it to the people for approval in the statewide referendum. It then received a 2 to 1 endorsement by the voters of Virginia.

Between the time of its popular approval and its official enactment into law by the General Assembly, apparent resentment grew over the section of this plan which allowed limited desegregation in certain areas and which accepted the principle of racial integration. Out of this resentment came a second plan different from the first in that it allowed no integration in any school and set the state directly in defiance of the court order to desegregate. This was the Stanley Plan, introduced by Governor Thomas B. Stanley.

Stanley Plan

The Stanley Plan withdrew pupil assignment authority from the local school boards and vested it in a central Placement Board, appointed by the Governor. It further provided that no state funds would go to any white school which enrolled a Negro pupil. In this way, no such school could operate as a part of the Virginia system when its classes were desegregated.

Some have argued that the Stanley Plan is unconstitutional and will lead the state to massive integration and a wrecked school system after the plan has failed in the courts. These persons contend that a policy of limited desegregation, even if this means only a handful of cases in the next decade, will be regarded by the Federal courts as sufficient progress in the right direction and that court pressure to integrate will therefore be lifted.

Advocates of the Stanley Plan on the other hand, believe that even token acceptance of integration will lead to its mass application in the schools of Virginia. They feel that any integration anywhere will destroy the public school system of our state.

To Prevent Integration

Both plans have a common goal–prevention of racial integration in the public schools. Where they differ is in this point. The Gray Plan says that the Supreme Court decision must be complied with if we are to avoid violent and forced integration in the schools. The Stanley Plan, however, favors open defiance of integration everywhere. It does not recognize the Supreme Court decision as law, and its proponents believe that "massive resistance" will nullify its effects on Virginia's schools.

The decision we, as students of this University, must make in today's poll is of vital importance. Whatever course is elected by our state leaders today will have to be applied by us tomorrow. If our state legislators are wise, they will regard what we decide here with seriousness. The problem is in their hands now but its effects will fall on our generation later. Because of this, we have a right to be instrumental in its solution.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 16 May 1957: 1

Sparse Voting Endorses Gray Plan

Students Favor Bill By Two-To-One Edge

'Limited Desegregation' Gets Nod; Poll Parallels Statewide Opinion

University students participating in yesterday's Cavalier Daily Opinion Poll endorsed the Gray Plan over the Stanley Plan by over a 2 to 1 margin. A total vote of only 488 was cast in the elections, which was considered "disappointing" by sponsors of the school segregation poll.

The two plans voted upon were measures considered in Virginia to meet the current school problems. The Stanley Plan, now law in the state, proposes total resistance against racial integration in the schools, whereas the heavily favored Gray Plan accepted a pupil assignment policy which would permit limited desegregation in certain areas.

The Gray Plan had been approved in a statewide referendum during January of 1956 an later disregarded in favor of the Stanley Plan when the legislature expressed the opinion that limited integration would be intolerable in Virginia schools.

Virginians favored the Gray Plan by approximately the same majority it received in the total student vote. Northerners voted Gray 3 to 1 and out-of-state Southerners were 3 to 2 in favor of the Gray Plan.

Totals were 312 Gray to 143 Stanley with 33 voting "neither" for the whole University. In-state students chose the Gray Plan 195 to 96 for Stanley. Out-of-state Southerners were [illegible] Gray and 25 Stanley. Northerners favored Gray 71 to 23.

Several ballots state that neither plan was constitutional, one said "we must have complete integration," and two called both plans incapable of stopping desegregation.

The vote from Virginians was nearly double that of out-of-state students, this margin being 291 to 156.

In total votes cast, the College led with 223, with Engineering casting 61, Law 52, Commerce 34, Education 25, Medical 15 and Graduate Business 11. 67 votes were cast in the Commons box.

The school most heavily favoring the Gray Plan was the Law where 35 voted with the Gray Plan, 6 for Stanley and 11 for "neither."

Alone among the other schools, the School of Medicine favored the defeated Stanley Plan 8 to 7.

This poll is the first one of its kind known to have been taken at a college or university on the subject of school segregation.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 17 May 1957: 2

Letter to the Editor

Dear Sirs,

In regards to your last poll, I believe that the lack of voting was not due to the dis-interest of the student body but rather to the haphazard way in which you organized your polling system. Due to your insufficient number, poor locations, and unmanned stations, the poll became a failure.

Sincerely, Fim Feeley

Editor's note—Ten ballot boxes were distributed throughout the University covering every school with the exception of the School of Architecture which, through an unfortunate error, was missed in the box placement. It would be difficult to administer a more comprehensive poll than this and we must conclude that it was more a lack of interest in the question asked than any other factor which contributed to the poor response.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

Below: Students walking from dorms to class, from Corks & Curls, the UVA yearbook (1957 edition, vol. 69, pp. 68).

Below: The photo that appeared on the front page of UVA's student newspaper, The Cavalier Daily, on 21 February 1958, the morning after Faulkner gave his speech on integration, titled "A Word to Virginians."

Caption: "BOYS CLUB CLIENTELE— Author William Faulkner (exiting door, with package) leaves the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Board establishment at 8th and Main Streets. Group of unidentified University students loiter nearby. Man on far right reads Spectator Magazine's new issue. Store is one of two in Charlottesville. — Staff Photo by Behlen."

The Grounds and the Fury: William Faulkner at the University, 1958

By Ken Ringle (College ’61)

God obviously created William Faulkner to explain the American South. He may have regretted it, because then He needed an army of scholars, critics and teachers to explain William Faulkner.

Those of us who found ourselves on the same campus with him half a century ago in Charlottesville needed at least that much aid. Faulkner himself was not much help at all. It wasn’t for lack of availability. The agreement that made him the University of Virginia’s first writer in residence in 1957 and 1958 specified that he keep regular office hours something like once a week. Those of us hoping to write our own selves into immortality (or at least into the arms of English majors at Sweet Briar) would show up to sit at his feet and study the muse.

Surprisingly, the regulars were a pretty small group, perhaps because the novelist rarely said much. He would lean back in his chair in his tweed sport coat, khakis and a green wool tie with little fox heads on it, then puff on his pipe and make infrequent gnomic pronouncements. We would sit there gaping, wracking our under-booked brains for some question that wouldn’t make us look stupid.

“Mr. Faulkner, in your short story ‘The Bear,’ do you consider the bear a positive nature symbol or a negative nature symbol or a symbol both positive and negative like the white whale in Moby-Dick?”

“Oh,” he’d eventually say in his thin, reedy voice, after puffing on his pipe long enough to raise the suspense: “That’s just a story about a bear.”

I was usually too intimidated to ask anything. Though I was certain I was destined to write the Great American Novel, I was mortified that I found his work unfathomable. How could I write a novel when I couldn’t even read his?

“Mr. Faulkner, how do you start a novel? How do you even know what you want to write about?”

Pause while he stroked his gray mustache.

“M’boy you have to write because you can’t not write. You have to be demon-driven by what’s inside you.” More pipe puffing. What the hell did that mean? It was years before I’d learn.

Stalking him for clues became a passion. Once, on my job shelving books at Alderman Library, I borrowed the key to the room in the stacks where he wrote. He’d just finished The Mansion and I thought the pictures on the wall, the books he used for reference, his general writing environment would give me clues on how to be a writer. I found the answer, but not the one I expected. The room was absolutely bare. There was nothing in it but one of the library’s standard oak tables and a chair, an upright Underwood typewriter and a big stack of writing paper. Nothing else. No books, no pictures or posters on the wall, no jottings, no comfy sweaters, not even a dictionary. It was all in his head. How depressing.

Undeterred, I soldiered on. Faulkner liked to wander around the university grounds and observe things, usually from beneath one of those little green Tyrolean hats with the shaving brush in the hatband. I would run across him regularly near Lambeth Field, where he used to idle at track practice. He showed little interest in the major university sports of football and lacrosse, but would spend hours timing sprinters and hurdlers with two stop watches that never seemed to agree.

I pondered that for clues. Maybe it had something to do with the horses in his books and stories. He rode to hounds with the Farmington Hunt and always rode horses too big for him, which greatly excited Freudians in the English department. But I wasn’t sure what it told me.

He didn’t appear demon-driven whenever I saw him. Just a meditative onlooker, galloping somewhere deep in his imagination.

Not all our encounters were planned. In the winter of 1958, as a photographer for the Cavalier Daily, I was stationed across from the Virginia ABC store on Charlottesville’s Main Street to get a shot of students stocking up for Midwinters weekend. I was framing the line snaking into the door on the right when out of the door on the left came William Faulkner. Wholly dwarfed by his enormous burden of bottle-packed shopping bags.

In those days college drinking was a source of more celebration than hand-wringing, particularly at Virginia, and we merrily ran the picture on the CD’s front page. The English department faculty was horrified. Faulkner was not. “They caught me,” he said with a grin.

The faculty reaction was symptomatic. In those days novelists didn’t hang around campuses much, believing real life a more profitable laboratory for observation. Faulkner was such a prize that obsequious professors all but laid their coats over puddles in his path. The writer himself, who lacked even a high school diploma and was famously disdainful of academics, remained polite but distant, countering scholars’ questions with mischievously opaque replies.

His agreement with the university specified that he was required to give no more than an occasional speech and no classroom lectures at all. But, in addition to keeping office hours, he was to answer questions periodically from both graduate and undergraduate students in a classroom setting. Thus he was regularly led before us like a trained bear to deepen the mystery of just what he meant by the biblical allusions in Light in August or the stained-glass imagery in Go Down, Moses. There was much tape-recording of all this, the results appeared years later in Frederick L. Gwynn and Joseph Blotner’s book Faulkner in the University. But Gwynn and Blotner edited out much of the mischief.

Unenlightened by such sessions and despairing of unlocking Faulkner on my own, I sought out a superb young English instructor named John Graham, who was far more passionate about nourishing learning than about nourishing cults of celebrity.

“I’m not surprised you found Faulkner difficult,” he said. ”You probably started off trying to read The Sound and the Fury.” I had. “Everyone does that. It’s his best-known book. But it’s also his most difficult.”

The way to read and appreciate William Faulkner, he said, was to take one of two routes. To just sample his power with language and as a teller of tales, he said, read “Old Man.” It’s a mesmerizing short novel – originally part of The Wild Palms – about the 1927 Mississippi flood and a convict trapped therein with a pregnant woman who, in one of literature’s great Gothic sequences, gives birth in a swamp atop an Indian mound aswarm with cottonmouth water moccasins.

To go further and understand Faulkner’s panoramic sweep of history, he said, one should start with The Unvanquished, a historical novel that’s one of his most accessible. It deals with the earliest years in his saga of the Southern aristocracy. Then read Absalom, Absalom! and Go Down, Moses, which continue the story of the aristocratic decline and focus on how that affects blacks. Then The Hamlet, which charts the rise of the poor white Snopes clan. Then, he said, you’re steeped in Faulkner’s mythical Yoknapatawpha County and its secrets of blood and history, and ready for all his other books, which weave in and out of the cultural stream he chronicles with such power.

Graham’s insight, which I’ve never seen published anywhere, finally unlocked William Faulkner for me. And as it did, his books became a passion and the writer himself seemed to open up. One day as we talked in his office, he presented me with an insight as valuable today as it was then.

“Mr. Faulkner,” I asked him “In your book As I Lay Dying, most of the characters are socially pretty reprehensible. The only one with any kind of sensitivity or nobility is Addie Bundren, the schoolteacher. Yet you have her marry Anse Bundren, absolutely the most dreadful of the whole lot. How can you justify that?” Faulkner rubbed his mustache and re-lit his pipe, then looked at me a long, long time.

“My boy,” he finally said in his slow drawl. “Haven’t you ever heard the story of the beautiful butterfly? That flitted from flower to flower? And lit at last on a horse turd?”

Despite the courtly charm with which he inevitably responded to those who approached him, Faulkner was normally reserved and, though he basically liked students, he appeared somewhat remote and most held him in awe.

But not all students were so cowed.

One who wasn’t was a fraternity brother of mine named Zeke Waters. Zeke was a jovial good-hearted guy but, like most of us then, did not over-exert himself in the classroom. He was always looking for shortcuts.

One spring evening we were lounging in he sun on the porch of the Beta House next to Beta Bridge before dinner. Zeke was panicked. He was an English major and the next day faced the dreaded senior “comprehensives”, the do-or-die examinations which in those days tested every student facing graduation on the entire body of knowledge absorbed in his major field of study over four years. Zeke was weak on American literature, and was looking for some quick fix to repair the situation. Where could he find it? he asked us. He got a few opinions but mostly shrugs. Then, from the direction of the Rotunda he spotted William Faulkner, walking home to his house up Rugby Road.

“That’s it!” said Zeke. “Faulkner knows all about American literature! He can tell me what I need to know!”

Now, I’m pretty sure Zeke had never read a line of Faulkner’s, but he was the most amiable and approachable of souls, and could make friends with a tree. He loped across Rugby road, greeted Faulkner and soon they disappeared together up the road and over the hill chatting, tall and lanky Zeke with his arm around Faulkner who was a kind of splendidly dapper but miniature man.

An hour or more went by. Zeke did not appear and we Betas went in to dinner without him. Finally, after dinner, Zeke showed up.

How did it go? we all wanted to know. Did Faulkner give you the keys to American literature?

“Well, not exactly,” said Zeke. “He couldn’t have been nicer and we talked about all sorts of things. But I never quite got him around to where I could ask the right question.”

It turned out Faulkner appeared glad to meet Zeke and grateful for the company on his homeward stroll. They chatted about the weather, the football weekend, where Zeke was from and other topics. When they got to Faulkner’s house, he asked Zeke in. He said his wife was away, the housekeeper was fixing dinner but he was going to have a drink first. Would Zeke like one too?

Zeke, like most students, never turned down a drink and soon they were seated companionably in Faulkner’s living room sipping good bourbon. The talk turned to horses, the pictures on the wall, the house – Faulkner liked Charlottesville because his daughter lived there – and so on. Faulkner suggested a second drink. Zeke accepted. There may have been a third.

“I was trying to think how to get him around to the literature question when the housekeeper came in and said dinner was ready,” Zeke said. “Faulkner is just the most courteous man in the world. He asked me to stay to dinner, saying there was plenty to eat. I protested no, I couldn’t do that, I was expected back at the Beta house. But I said I would come in the dining room with him and finish my drink while he ate. I was still trying to work him around to American literature.”

The housekeeper had arranged the small dining room beautifully, Zeke reported, with crystal, wine glasses, a vase of flowers and so on, all set off by a splendid white table cloth. Faulkner sat down and began spooning his soup. Zeke stood against the wall with his glass of bourbon, making conversation, trying desperately to turn the talk to books.

“That’s when it happened,” Zeke said. “For some reason I crossed my legs while I was standing there talking and thinking, and I lost my balance.”

Down he slowly toppled, grabbing desperately for support. He caught the end of the tablecloth. Off came the tablecloth, the vase, the glasses, the flowers, Faulkner’s soup, everything. The sound of crashing crockery and glass, Zeke said, seemed to go on forever.

Faulkner, who had somehow escaped both injury and stains, was unconcerned by the mess. He was worried Zeke might have hurt himself. He picked Zeke up, brushed him off, apologized for the incident and asked once again if Zeke wouldn’t stay and share the rest of the dinner.

“But I decided it was time to leave,” Zeke said. “Because even though I hadn’t had a chance to ask him about literature and even though Faulkner could not have been nicer, that housekeeper was really, REALLY pissed off.”

I can’t remember if Zeke passed his comprehensives.

©2009 Ken Ringle

Ken Ringle retired in 2003 after 33 years as a writer, editor, essayist and critic for The Washington Post. His work has also appeared in The National Geographic, Smithsonian, European Affairs and other publications, and he has been a writer-in-residence himself as a Washington Post Fellow at Duke University.

The Cavalier Daily 25 February 1958: 2

Mr. Faulkner On Segregation

To all who heard William Faulkner speak last Thursday night on the subject of segregation, it was readily apparent that our writer-in-residence is no orator. Mr. Faulkner was able to stretch his speech out to only fifteen minutes, which was disappointing to us, for his speech was widely publicized and his audience was composed of the most distinguished citizenry of the University community. And Faulkner read his speech, an unforgivable sin in oratorical circles.

BUT THE evening was not totally disappointing. Regardless of his speaking ability, the novelist did offer what we believe to be the only working solution to the biggest social problem in the South in the text of his speech and during the questioning period. Faulkner's main premise for his proposals can be summed up in one word, "education." And we have been stressing the value of that premise for the last three weeks.

Faulkner's proposals were based on his observations of Negroes from Mississippi to Virginia. Considering his insight into human nature as evidenced in his novels, and his acquaintance with Negroes and their problems (we have heard that he sits on a nail keg down by the liquor store on Vinegar Hill observing and taking notes) we feel that his proposals have much merit and are worthy of review.

In his speech, Faulkner offered the view that the Negro wants the right to decide for himself whether to mix. And this cannot be done without education. The Negro, Faulkner pointed out, believes the white schools are fundamentally better than Negro schools, and that is his reason for wanting integration.

And he also pointed out that economic equality should be the goal to be strived for, rather than social equality. The author believed that once the Negro did obtain economic equality, which can only be accomplished through education, then he would have the right to decide for himself whether to mix, and probably would defend segregation when he could decide for himself.

As for integrating schools, Faulkner indicated that Negro students should be given the right to choose between white and Negro schools, and that qualified Negroes should be allowed to go to white schools. Such qualification would be based on entrance examinations. And he also observed that no one, not even white people, should be forced to go to school, and that laws requiring education should be abolished. The writer reserved a half century for any such educational program or educational equality to establish itself.

WE FEEL that Faulkner's proposal offers the compromise between the dogmatism of the North and the South on the subject. And we could remind the North again that the problem is fundamentally our own, and that helpful advice will do more to alleviate the situation rather than biased and unsound criticism.

Mr. Faulkner's speech, entitled "A Message to Virginians" was directed toward the prominence which Virginia has held and still holds in the South as a leader. His idea was that it was up to the "Old Dominion" state to take up the banner of education for the Negro and assume its position of leadership in solving this century old problem.

Two points which Mr. Faulkner only briefly touched were the educational problems of white people in the South and the failure of Virginia in the immediate past to assume its rightful position of leadership of the Southern states. We intend to discuss, in subsequent editorials, these two subjects.

©1958 The Cavalier Daily

Below: the Department of English at the University of Virginia in 1960, two years after Faulkner finished his second term as Writer-in-Residence. By this time Frederick Gwynn has left UVA, as probably have several other faculty members, and some of the men in this photo probably weren't in the Department in 1957-1958. Names of the instructors whose voices have been identified on the tapes are in bold. The two women in the picture were departmental secretaries.

Top row: John Carter, William Manierre, William Mosler, John Graham, Nolan Smith, Robert Kellogg, Lee Potter,

Rex Worthington

Middle row: Adele Hall, Calhoun Winton, Joseph Blotner, John Coleman, Robert Scholes,

Robert Ganz, Irby Cauthen, James Colvert, Charlotte Lauck

Bottom row: Robert West, Floyd Stovall, Archibald Shepperson, Edgar Shannon,

Atcheson Hench, Arthur Kyle Davis, Fredson Bowers

Below: the dust jacket of the first edition of Pylon (1935), with a representation of the pylon the pilots race around on its spine:

The Cavalier Daily 16 February 1957: 1

Faulkner Begins Stay As Writer-In-Residence

Author Gives Press Conference; Goal Is Helping Student Writers

By Andrew Ruckman, II

Author William Faulkner yesterday initiated his stay at the University as writer-in-residence with a morning press conference, during which newsmen fired a variety of questions at the Nobel and Pulitzer prize winner.

Faulkner, wearing a collegiate tweed suit, sat quietly while a battery of photographers took numerous pictures of him and the bristling mustache and pipe that are his trademarks. He then replied to queries about his opinions on topics ranging from writing to integration and international politics.

The author described his goal during his residence at the University as a desire to help students interested in creative writing "out of my experience as a writer, and to help create an atmosphere."

Speaks Informally

Faulkner, seated at a conference table in a crowded Cabell Hall classroom, spoke informally and without notes. In addition to his literary achievements, he serves the U.S. State Department in an advisory capacity.

He answered a question about the mid-Eastern situation by stating that "What we need now is not a golf player but a good poker player" in the White House.

The writer-in-residence categorized the "greatest" American novelists according to the unique standard of "the splendor of their failures to attain the dream which all first-rate writers hold."

High On Own List

In descending order of greatness, Faulkner listed Thomas Wolfe, himself, John Dos Passos, Erskine Caldwell, and Ernest Hemingway. He described the most important considerations in literary craftsmanship as "characters, ideas, and the plot."

At least two of Faulkner's works feature one character who attended the University of Virginia, but the author stated that most of the figures in his works are not actually persons of his acquaintance, but rather composites taken from "observation and impression."

No College Education

Faulkner spoke of himself as "not a literary man." In reply to a question about the value of a college education to a prospective writer, he said "No man can write who is not first a humanitarian. If he is such, college can be of infinite importance. But I don't think that college makes a writer." Faulkner also pointed out that he himself had not gone to college

He told reporters that he has "never written the one that suits me," and said that all "first rate" authors strive for a goal that is impossible for them to realize. Faulkner added, "I'm lazy . . . writing is work, but simply will not let me rest in peace. It worries me sometimes." He did feel that writers such as Cervantes, Shakespeare, and Homer had achieved the elusive goal.

A newsman asked Faulkner if he wrote "more easily" than he did when he was younger, and the author replied that "I fumble less now, but put (working) off more. I'm convinced that I'll live to be 100."

The Mississippi-born author, famed for his penetrating portrayals of the South, spoke at length on the current integration of schools. "The schools are poor, and should be improved to the standards of the best students, no matter what color," he said.

"The negro must earn the responsibility to be equal. There is more to a right than just the gift of it. We should not bother keeping the negro out, but should raise the standards and possibly keep some of the whites out," Faulkner added.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

Faulkner and an Undergraduate

By Gerald L. Cooper (College ’58, M.Ed. Guidance ’69)

Upon graduation from Christchurch School in June 1953, I entered and quickly left Princeton University in September, disenchanted. I attended the College of William and Mary for three semesters happily, and then transferred to the University of Virginia in January 1955, to pursue a major in English. A year or so later I found myself in a small lecture hall, straining to hear a world-renowned writer-in-residence who spoke in an almost inaudible voice using an extraordinary accent. He described a mythical place with an Indian-sounding name: Yoknapatawpha. That reminded me of my own place of origin: the shores of the Rappahannock.

The speaker was William Faulkner, whom I had heard of from another native Mississippian, Robert M. Yarbrough Jr., instructor in senior English at Christchurch. Bob had introduced me to Faulkner’s novels The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying outside of class.

Someone in the audience that day in 1957 at the University of Virginia asked Mr. Faulkner to give his view of promising young American writers. Violating his policy against endorsing writers, he replied that one of the best was from right here in Virginia: “His name is William Styron, and his book is titled Lie Down In Darkness.” Deciphering Faulkner’s low-pitched, Miss’sippi drawl with no amplification from my seat on the back row of the small auditorium in Rouss Hall, I realized he had spoken the name of a graduate of my old school – William Styron, known to his Christchurch classmates as “Sty.” I had attended the graduation of the Class of 1942 at Christchurch, to honor my friend and mentor, Jim Davenport, a member of that class, along with Styron and about fourteen others. By 1957 I had also read Lie Down In Darkness, Styron’s first book, that he published in 1951 and that won the Prix de Rome.

Several daily newspapers reported Faulkner’s public recognition of William Styron, including the Washington Post and the Richmond Times-Dispatch. Thereafter I found it more comfortable to mention around the Grounds that I was a graduate of Christchurch. Both the University’s English professors and my fellow students, some of whom were graduates of well-known prep schools like Woodberry Forest, Episcopal High, and Lawrenceville, suddenly sounded respectful of Christchurch, that unpretentious school with the million-dollar view on a bank overlooking the Rappahannock River.

I completed a bachelor’s degree in English at the University of Virginia in December 1957, a year after William Faulkner arrived as writer-in-residence. I had several opportunities to hear Mr. Faulkner discuss his writing between January and December of 1957. Although I was not among the favorites of the English department’s English majors, and therefore not invited to special gatherings with Mr. Faulkner, it was possible nonetheless to find “Old Bill” around the Grounds, occasionally at fraternities. I remember his quiet presence one evening in the Serpentine Club, at the back of the Quadrangle. (I knew the location of every fraternity because one of my part-time jobs was delivering beer kegs to the fraternities from Carroll’s Tea Room.)

In that setting Mr. Faulkner was less reticent than he was in small English seminars or honors classes. His painful shyness in one-to-one settings became well-known in New Cabell Hall, and not many students signed up for those uncomfortable meetings. Perhaps he was under-utilized, as some have suggested.

Even peripheral undergraduate students such as I were aware that factions within the English department – and perhaps among the entire University administration – were in disagreement over the value of Mr. Faulkner’s presence and usefulness on the Grounds. Former professor of English Joseph Blotner has captured much of the color, along with some of the political issues, of that era at the University in his autobiographical work, An Unexpected Life, published in 2005. The chapter titled “The University and Mr. Faulkner” might more accurately be titled “The Faulkner Era at the University of Virginia.”

Despite the politics and controversy, William Faulkner had a remarkable impact in the brief period of his presence in Charlottesville. His time on the Grounds is comparable to the presence of Edgar Allan Poe, who was enrolled for one academic year, beginning February 1, 1826, in just the University’s second session.

The University of Virginia’s first president, Edwin A. Alderman, wrote in 1925 a convincing essay on Edgar Allan Poe’s tenure as a student. He describes how Poe, despite a short stay and a less than exemplary lifestyle, had symbolized the presence of a “world poet” at the University. Alderman concludes that Poe “has contributed an irreducible total of good to the spirit which men breathe [at the University] as well as a wide fame to his alma mater that will outlive all disaster, or change, or ill-fortune.” Alderman defines the effect that a true artistic talent may have upon a community of scholars – even when that presence is brief and controversial.

Blotner and others have reported that President Colgate Darden was lukewarm to Faulkner’s writer-in-residence status because he questioned that the University needed the national attention that Faulkner’s visit would bring. But from my point of view, William Faulkner’s presence on the grounds had the effect of opening a window onto a larger world for UVA students in the late 1950s. It is difficult for students in the 21st century to imagine what a great gulf existed between the Grounds and the larger worlds of government, commerce and especially the arts, before the advent of mass communications. No national media coverage originated in Charlottesville, and even Washington, D.C. offered little or no live theatre, at least until the Kennedy Center opened in 1971. Thus to have a person of international stature in the world of letters – a Nobel laureate – walking the Grounds daily over a period of months and years demonstrated that the University of Virginia had not lost sight of the world-class ambitions of its founder.

I’ve had an enduring interest in the University of Virginia ever since I arrived on the Grounds some fifty-three years ago as a “transfer” from another college. Perhaps that’s why I view the University from a different perspective than does the typical alumnus of any era before the 1970s. I have devoted a chapter in my ebook to the University of today, titled “Leading to Diversity,” highlighting the changes that I see as having occurred under the leadership of President John T. Casteen III.

I am happy to observe that gone are the days of a stereotyped faculty and student body, and of a laissez faire attitude toward diverse students that I experienced when I attended in the 1950s. As Mr. Jefferson the Francophile might have said, Vive la difference!

Gerald L. Cooper divided his 43-year career as an administrator, counselor and teacher among four preparatory schools, two colleges, and finally as executive director of a college access program [501 (c) (3)] that served ten public high schools in Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Virginia Beach. This essay derives from his ebook, On Scholarship – From An Empty Room at Princeton, available in PDF format online at “http://www.talkeetna.com/OnScholarship/index.html” . In it he describes his personal experiences with financial aid: receiving it, granting it, fundraising for it, and finding it for needy students.

President Alderman’s remarks about Poe can be found in “Edgar Allan Poe and the University of Virginia” (The Virginia Quarterly Review, spring 1925), reprinted in We Write for Our Own Time: Selected Essays from the Virginia Quarterly Review (Charlottesville, 2000).

©2010 Gerald L. Cooper

Faulkner and an Undergraduate

By Gerald L. Cooper (College ’58, M.Ed. Guidance ’69)

Upon graduation from Christchurch School in June 1953, I entered and quickly left Princeton University in September, disenchanted. I attended the College of William and Mary for three semesters happily, and then transferred to the University of Virginia in January 1955, to pursue a major in English. A year or so later I found myself in a small lecture hall, straining to hear a world-renowned writer-in-residence who spoke in an almost inaudible voice using an extraordinary accent. He described a mythical place with an Indian-sounding name: Yoknapatawpha. That reminded me of my own place of origin: the shores of the Rappahannock.

The speaker was William Faulkner, whom I had heard of from another native Mississippian, Robert M. Yarbrough Jr., instructor in senior English at Christchurch. Bob had introduced me to Faulkner’s novels The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying outside of class.

Someone in the audience that day in 1957 at the University of Virginia asked Mr. Faulkner to give his view of promising young American writers. Violating his policy against endorsing writers, he replied that one of the best was from right here in Virginia: “His name is William Styron, and his book is titled Lie Down In Darkness.” Deciphering Faulkner’s low-pitched, Miss’sippi drawl with no amplification from my seat on the back row of the small auditorium in Rouss Hall, I realized he had spoken the name of a graduate of my old school – William Styron, known to his Christchurch classmates as “Sty.” I had attended the graduation of the Class of 1942 at Christchurch, to honor my friend and mentor, Jim Davenport, a member of that class, along with Styron and about fourteen others. By 1957 I had also read Lie Down In Darkness, Styron’s first book, that he published in 1951 and that won the Prix de Rome.

Several daily newspapers reported Faulkner’s public recognition of William Styron, including the Washington Post and the Richmond Times-Dispatch. Thereafter I found it more comfortable to mention around the Grounds that I was a graduate of Christchurch. Both the University’s English professors and my fellow students, some of whom were graduates of well-known prep schools like Woodberry Forest, Episcopal High, and Lawrenceville, suddenly sounded respectful of Christchurch, that unpretentious school with the million-dollar view on a bank overlooking the Rappahannock River.

I completed a bachelor’s degree in English at the University of Virginia in December 1957, a year after William Faulkner arrived as writer-in-residence. I had several opportunities to hear Mr. Faulkner discuss his writing between January and December of 1957. I was not among the elect of the English department’s English majors, and therefore I was not invited to special gatherings with Mr. Faulkner. It was possible nonetheless to find “Old Bill” around the Grounds, occasionally at fraternities. I remember his quiet presence one evening in the Serpentine Club, at the back of the Quadrangle. (I knew the location of every fraternity because one of my part-time jobs was delivering beer kegs to the fraternities from Carroll’s Tea Room.)

In that setting Mr. Faulkner was less reticent than he was in small English seminars or honors classes. His painful shyness in one-to-one settings became well-known in New Cabell Hall, and not many students signed up for those uncomfortable meetings. Perhaps he was under-utilized, as some have suggested.

Even peripheral undergraduate students such as I were aware that factions within the English department – and perhaps among the entire University administration – were in disagreement over the value of Mr. Faulkner’s presence and usefulness on the Grounds. Former professor of English Joseph Blotner has captured much of the color, along with some of the political issues, of that era at the University in his autobiographical work, An Unexpected Life, published in 2005. The chapter titled “The University and Mr. Faulkner” might more accurately be titled “The Faulkner Era at the University of Virginia.”

Despite the politics and controversy, William Faulkner had a remarkable impact in the brief period of his presence in Charlottesville. His time on the Grounds is comparable to the presence of Edgar Allan Poe, who was enrolled for just one academic year, beginning February 1, 1826, in the second session at the University of Virginia.

The University of Virginia’s first president, Edwin A. Alderman, wrote in 1925 a convincing essay on Edgar Allan Poe’s brief time as a student at the University. He described how Poe, despite a short stay and a less than exemplary lifestyle, had symbolized the presence of a “world poet” at the University. Alderman concluded that Poe “has contributed an irreducible total of good to the spirit which men breathe [at the University] as well as a wide fame to his alma mater that will outlive all disaster, or change, or ill-fortune.” Alderman defined the effect that a true artistic talent may have upon a community of scholars – even when that presence is brief and controversial.

Mr. Faulkner’s arrival on the Grounds signaled the presence of another “world writer” equal in stature to Edgar Allan Poe and Thomas Jefferson, who had dominated the University of Virginia’s pantheon of genius for generations. Blotner and others reported that President Colgate Darden was lukewarm to Faulkner’s writer-in-residence status because he questioned that the University needed the national attention that Faulkner’s visit would bring.

I’ve had an enduring interest in the University of Virginia ever since I arrived on the Grounds some fifty-three years ago as a “transfer” from another college. Perhaps that’s why I view the University from a different perspective than does the typical alumnus of any era before the 1970s. I have devoted a chapter in my forthcoming book to the University of today, titled “Leading to Diversity,” highlighting the changes that I see as having occurred under the leadership of President John T. Casteen III.

I am happy to observe that gone are the days of a stereotyped faculty and student body, and of a laissez faire attitude toward diverse students that I experienced when I attended in the 1950s. As I see it today: