Introduction and Contexts

- Faulkner At Virginia: Introduction

- Faulkner in the Late 1950s

- The US in the Late 1950s

- Virginia in the Late 1950s

The U.S. in the Late 1950s

For most of the country, the two academic years containing Faulkner’s terms as Writer-in-Residence (1956-1957 and

1957-1958) were relatively quiet, especially after the crises of the previous decades: the Great Depression, the Second World War,

and the onset of the global “war” against Communism that was both “hot” (on the Korean

peninsula) and “cold” (in the various diplomatic, economic, strategic and propagandistic struggles against

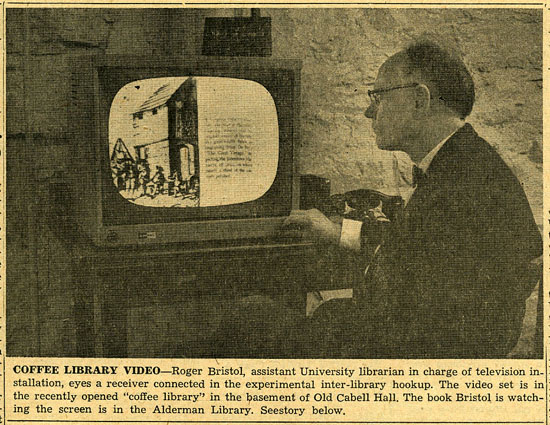

Soviet Russia). In the late nineteen-fifties the U.S. economy continued to grow at record rates, moving more people into the

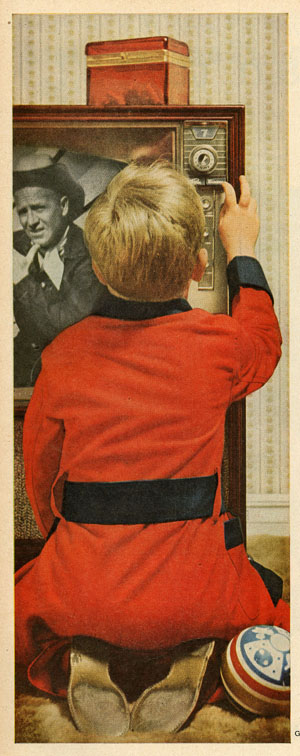

middle class and out to the suburbs. The growing families created by the Baby Boom were learning new routines from the recently

purchased black-and-white TV sets in their living rooms. The re-election of President Eisenhower created little suspense and no

controversy. Just about the same time that UVA students returned to Charlottesville for the start of the Fall 1956 semester,

however, three events occurred that would still be reverberating in the national consciousness and on the front pages of the

student newspaper when Faulkner took up his residency the following February: the Suez Crisis, the Hungarian Revolution and, much

closer to home, the conflict over integrating America’s public schools – which was also, in different parts of

the South, both “hot” and “cold.”

For most of the country, the two academic years containing Faulkner’s terms as Writer-in-Residence (1956-1957 and

1957-1958) were relatively quiet, especially after the crises of the previous decades: the Great Depression, the Second World War,

and the onset of the global “war” against Communism that was both “hot” (on the Korean

peninsula) and “cold” (in the various diplomatic, economic, strategic and propagandistic struggles against

Soviet Russia). In the late nineteen-fifties the U.S. economy continued to grow at record rates, moving more people into the

middle class and out to the suburbs. The growing families created by the Baby Boom were learning new routines from the recently

purchased black-and-white TV sets in their living rooms. The re-election of President Eisenhower created little suspense and no

controversy. Just about the same time that UVA students returned to Charlottesville for the start of the Fall 1956 semester,

however, three events occurred that would still be reverberating in the national consciousness and on the front pages of the

student newspaper when Faulkner took up his residency the following February: the Suez Crisis, the Hungarian Revolution and, much

closer to home, the conflict over integrating America’s public schools – which was also, in different parts of

the South, both “hot” and “cold.”

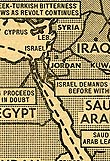

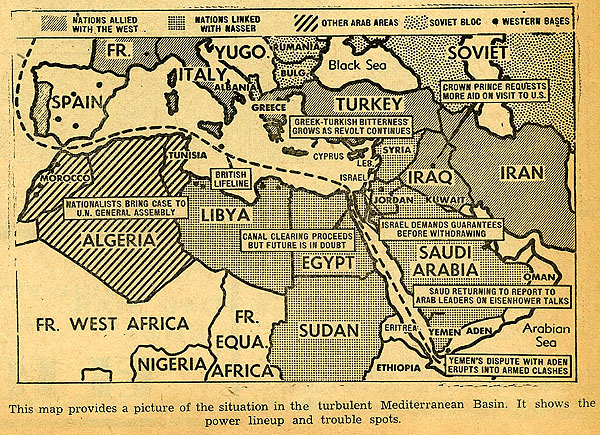

The Suez Crisis began in the summer of 1956, when Egypt’s President, Gamal Adbul Nasser, nationalized the Canal. In

an effort to regain control of it, Britain and France secretly planned with Israel for the new Jewish state to invade Egypt,

allowing the two European countries to intervene militarily to take possession of the Canal in the guise of securing it for world

commerce. Beginning with the Israeli attack in October, 1956, this crisis became the most

frequently covered international news story in Virginia’s student newspaper, The Cavalier Daily,

perhaps because (although the U.S. was not directly involved except through diplomatic efforts to end the hostilities) fighting in

the Middle East made UVA students very conscious of the draft cards they carried in their wallets. Publically, at least, in the

American media the crisis was not viewed as a conflict between the Arab world and the West, but as another theater in the Cold

War: behind Nasser’s actions the U.S. feared the specter of Soviet influence. The oil that flowed from wells in the

Middle East in tankers through the Canal into the big cars Americans drove could not be allowed to fall under Russian control. The

result of that anxiety was the Eisenhower Doctrine, announced in January, 1957, in which the U.S. pledged to support, militarily

if necessary, any threatened country that requested its aid. A year later, Marines were sent to Lebanon as a result.

The Suez Crisis began in the summer of 1956, when Egypt’s President, Gamal Adbul Nasser, nationalized the Canal. In

an effort to regain control of it, Britain and France secretly planned with Israel for the new Jewish state to invade Egypt,

allowing the two European countries to intervene militarily to take possession of the Canal in the guise of securing it for world

commerce. Beginning with the Israeli attack in October, 1956, this crisis became the most

frequently covered international news story in Virginia’s student newspaper, The Cavalier Daily,

perhaps because (although the U.S. was not directly involved except through diplomatic efforts to end the hostilities) fighting in

the Middle East made UVA students very conscious of the draft cards they carried in their wallets. Publically, at least, in the

American media the crisis was not viewed as a conflict between the Arab world and the West, but as another theater in the Cold

War: behind Nasser’s actions the U.S. feared the specter of Soviet influence. The oil that flowed from wells in the

Middle East in tankers through the Canal into the big cars Americans drove could not be allowed to fall under Russian control. The

result of that anxiety was the Eisenhower Doctrine, announced in January, 1957, in which the U.S. pledged to support, militarily

if necessary, any threatened country that requested its aid. A year later, Marines were sent to Lebanon as a result.

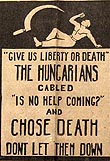

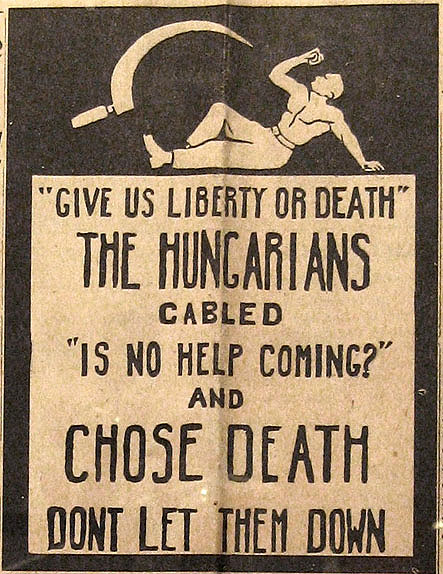

The revolution in Hungary was short-lived, lasting for about three weeks in October and November 1956. At the end of the

1940s, Russian-backed nationals – supported by the presence of the Red Army that had liberated the country from the

Nazis during World War II – turned Hungary into a Communist state. The 1956 Revolution began with a student

demonstration in Budapest demanding more freedom for themselves and autonomy for their country. Within about ten days, the

rebellion had spread throughout the populace: the Communist government was toppled, and at the end of October, as its leaders fled

to Russia and the Soviet garrisons withdrew, it seemed as if a new Hungary would emerge. On 4 November, however, an overwhelming

force of Russian tanks invaded the country. Over 2500 Hungarians were killed in the fighting that followed, thousands were

arrested, the new government was deposed and the Hungarian Revolutionary Worker-Peasant Government set up in its place. Western

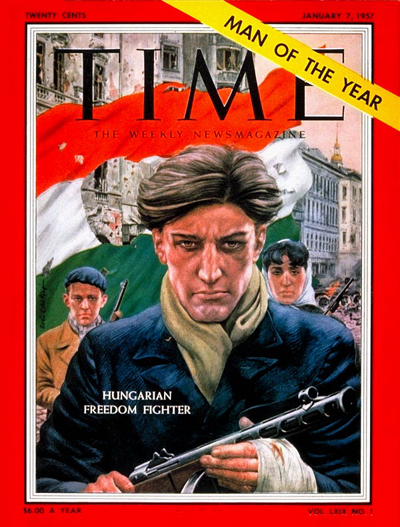

Europe, the U.S. and the United Nations all condemned the Soviet “intervention.” In January 1957 Time

Magazine named “The Hungarian Freedom Fighter” its

“Man of the Year.” But the international response to this event was confined largely to sympathy for the

Hungarians and indignation against the Soviets. At UVA students found various ways to express both those emotions, including a campaign for aid to relieve suffering in Hungary, but in the West the larger effect of

the images of Russian tanks subduing a populace seemed to be an escalation in anxieties about the Communists’ designs on

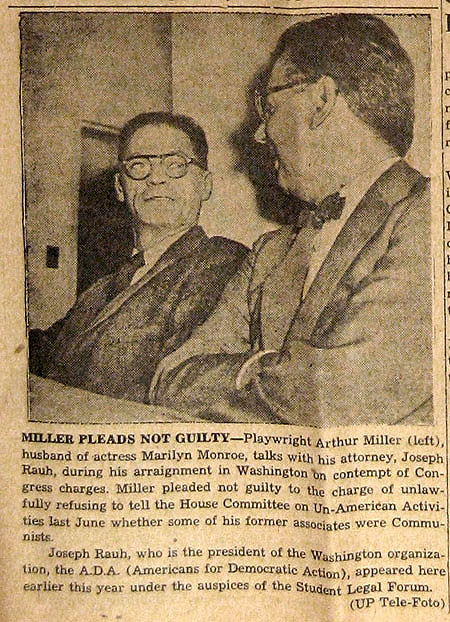

world domination. Senator Joe McCarthy’s incendiary exploitation of that threat had effectively ended by 1955. He died

during Faulkner’s first term, prompting a favorable editorial in The

Cavalier Daily and a question for Faulkner about “McCarthyism”

The revolution in Hungary was short-lived, lasting for about three weeks in October and November 1956. At the end of the

1940s, Russian-backed nationals – supported by the presence of the Red Army that had liberated the country from the

Nazis during World War II – turned Hungary into a Communist state. The 1956 Revolution began with a student

demonstration in Budapest demanding more freedom for themselves and autonomy for their country. Within about ten days, the

rebellion had spread throughout the populace: the Communist government was toppled, and at the end of October, as its leaders fled

to Russia and the Soviet garrisons withdrew, it seemed as if a new Hungary would emerge. On 4 November, however, an overwhelming

force of Russian tanks invaded the country. Over 2500 Hungarians were killed in the fighting that followed, thousands were

arrested, the new government was deposed and the Hungarian Revolutionary Worker-Peasant Government set up in its place. Western

Europe, the U.S. and the United Nations all condemned the Soviet “intervention.” In January 1957 Time

Magazine named “The Hungarian Freedom Fighter” its

“Man of the Year.” But the international response to this event was confined largely to sympathy for the

Hungarians and indignation against the Soviets. At UVA students found various ways to express both those emotions, including a campaign for aid to relieve suffering in Hungary, but in the West the larger effect of

the images of Russian tanks subduing a populace seemed to be an escalation in anxieties about the Communists’ designs on

world domination. Senator Joe McCarthy’s incendiary exploitation of that threat had effectively ended by 1955. He died

during Faulkner’s first term, prompting a favorable editorial in The

Cavalier Daily and a question for Faulkner about “McCarthyism”

. “Hungary” is not specifically mentioned in any of the fourteen hundred questions on the tapes, but much

of the discussion of current events in his UVA sessions is clearly informed by Cold War anxieties.

. “Hungary” is not specifically mentioned in any of the fourteen hundred questions on the tapes, but much

of the discussion of current events in his UVA sessions is clearly informed by Cold War anxieties.

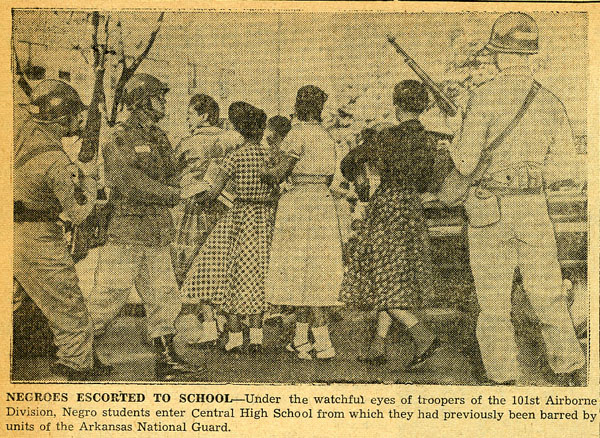

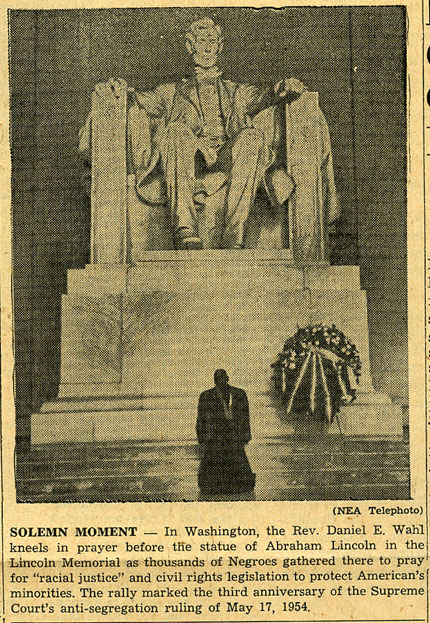

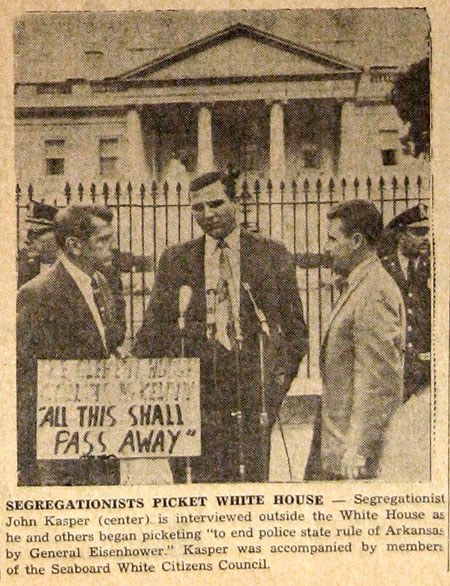

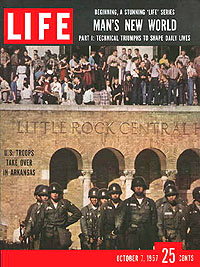

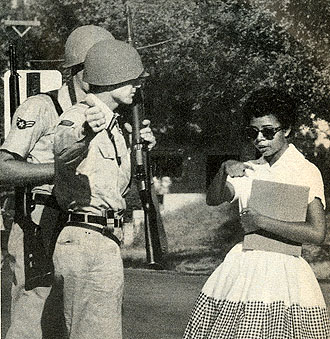

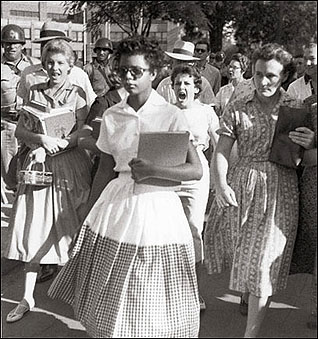

Although it expressed very little support for the African Americans who were using non-violent tactics to fight for freedom in

this country, The Cavalier Daily did report extensively on efforts to enroll

black students in previously segregated southern schools, and on the forms of resistance to this revolution that emerged. The

Civil Rights Movement was in its early stages in 1956-1958. The Montgomery Bus Boycott that began late in 1955 ended a year later,

when the Supreme Court affirmed that Alabama’s Jim Crow public transportation system was unconstitutional. By 1956 the

Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v Board of Education was getting its first practical tests outside as well as

inside American schools, as angry whites gathered to prevent the court-ordered integration of previously segregated school

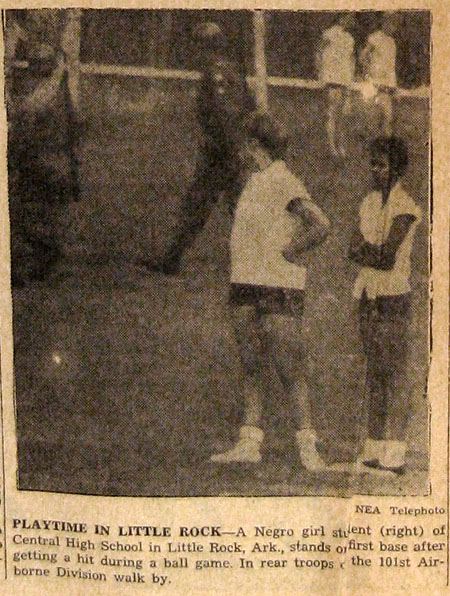

systems. The beginning of the school year was a particularly eventful period in both 1956 and 1957. In 1956 there was violence

(including a bombing) by white protestors in Clinton, Tennessee, and in September, 1957,

Eisenhower sent U.S. troops into Little Rock, Arkansas, to protect black schoolchildren from violent mobs – Faulkner

mentions both sites when addressing Virginians on this issue in February, 1958. For white Americans in the North, those new

television sets brought home with unprecedented vividness the discrimination and injustice that black Americans in the South were

subjected to. For many Americans this issue also had important implications for the Cold War: how could the U.S. compete against

Soviet propaganda for the hearts and minds of people in the Third World when pictures of hateful mobs and uniformed sheriffs

intimidating and beating peaceful black protestors and their children gave the lie to claims about “freedom”

and “democracy”? For the white South, at least publically, such abstract considerations were meaningless

compared to the visceral sense of being under attack by “outlanders” (as Faulkner liked to call northerners

Although it expressed very little support for the African Americans who were using non-violent tactics to fight for freedom in

this country, The Cavalier Daily did report extensively on efforts to enroll

black students in previously segregated southern schools, and on the forms of resistance to this revolution that emerged. The

Civil Rights Movement was in its early stages in 1956-1958. The Montgomery Bus Boycott that began late in 1955 ended a year later,

when the Supreme Court affirmed that Alabama’s Jim Crow public transportation system was unconstitutional. By 1956 the

Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v Board of Education was getting its first practical tests outside as well as

inside American schools, as angry whites gathered to prevent the court-ordered integration of previously segregated school

systems. The beginning of the school year was a particularly eventful period in both 1956 and 1957. In 1956 there was violence

(including a bombing) by white protestors in Clinton, Tennessee, and in September, 1957,

Eisenhower sent U.S. troops into Little Rock, Arkansas, to protect black schoolchildren from violent mobs – Faulkner

mentions both sites when addressing Virginians on this issue in February, 1958. For white Americans in the North, those new

television sets brought home with unprecedented vividness the discrimination and injustice that black Americans in the South were

subjected to. For many Americans this issue also had important implications for the Cold War: how could the U.S. compete against

Soviet propaganda for the hearts and minds of people in the Third World when pictures of hateful mobs and uniformed sheriffs

intimidating and beating peaceful black protestors and their children gave the lie to claims about “freedom”

and “democracy”? For the white South, at least publically, such abstract considerations were meaningless

compared to the visceral sense of being under attack by “outlanders” (as Faulkner liked to call northerners

); to these people, those paratroopers in Little Rock (the first time that federal troops had been deployed in the South

since the end of Reconstruction) probably looked like the Soviet tanks rolling into the streets of Budapest. Determined to defend

the racial status quo, during the second of Faulkner’s terms here the Commonwealth of Virginia formally embraced the

policy of “Massive Resistance,” under which public schools were simply closed down rather than allow black

students into previously “white” classrooms. In Faulkner’s UVA audiences one can hear both

considerable defensiveness about the racial traditions – which is to say, the racist system – they had grown

up with, and uncertainty about what the current turmoil might lead to.

); to these people, those paratroopers in Little Rock (the first time that federal troops had been deployed in the South

since the end of Reconstruction) probably looked like the Soviet tanks rolling into the streets of Budapest. Determined to defend

the racial status quo, during the second of Faulkner’s terms here the Commonwealth of Virginia formally embraced the

policy of “Massive Resistance,” under which public schools were simply closed down rather than allow black

students into previously “white” classrooms. In Faulkner’s UVA audiences one can hear both

considerable defensiveness about the racial traditions – which is to say, the racist system – they had grown

up with, and uncertainty about what the current turmoil might lead to.

As far as I can tell, there were neither Russian Communists nor American blacks in any of those audiences, but both were often

present in the minds of the people who were there. If anything, tension about these issues grew over the two years recorded on the

tapes. At the start of his second term, Faulkner himself chose to make the struggle against segregation the topic of one of the

two formal speeches he gave here. The other, “A Word to Young Writer’s,” given in April 1958, begins

by talking about the People-to-People program that Faulkner had participated in at Eisenhower’s request, thus locating

the American writer in relation to the battle lines of the Cold War. When he was asked about specific ways to “combat

communism,” he put his faith in individualism

As far as I can tell, there were neither Russian Communists nor American blacks in any of those audiences, but both were often

present in the minds of the people who were there. If anything, tension about these issues grew over the two years recorded on the

tapes. At the start of his second term, Faulkner himself chose to make the struggle against segregation the topic of one of the

two formal speeches he gave here. The other, “A Word to Young Writer’s,” given in April 1958, begins

by talking about the People-to-People program that Faulkner had participated in at Eisenhower’s request, thus locating

the American writer in relation to the battle lines of the Cold War. When he was asked about specific ways to “combat

communism,” he put his faith in individualism

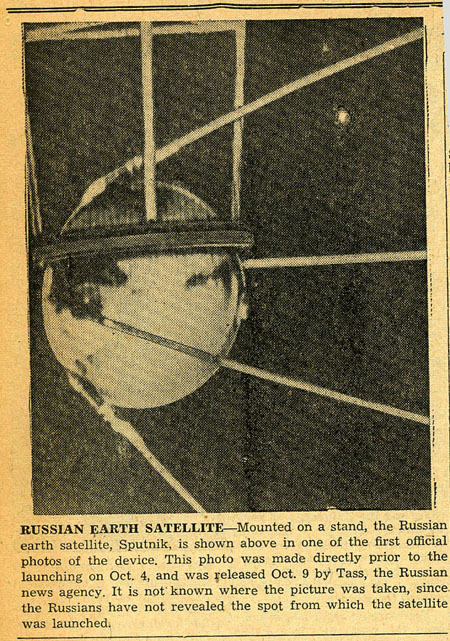

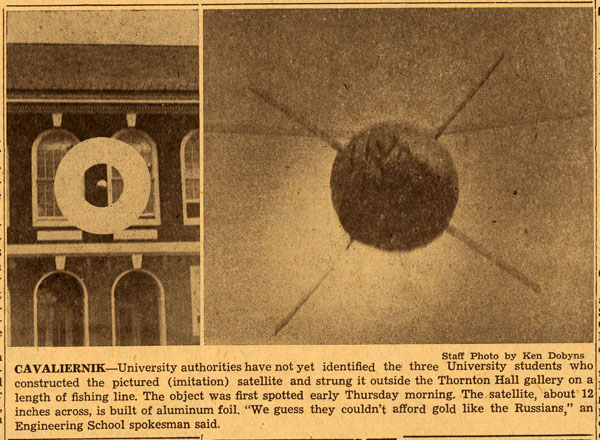

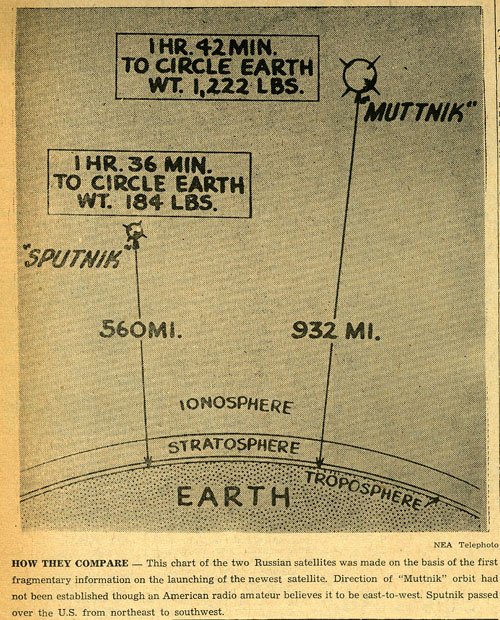

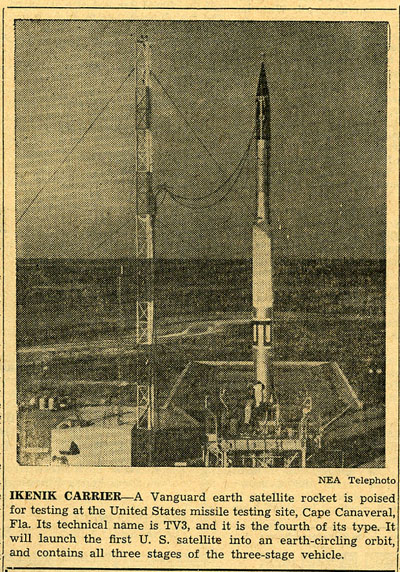

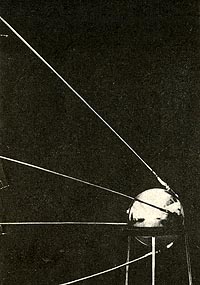

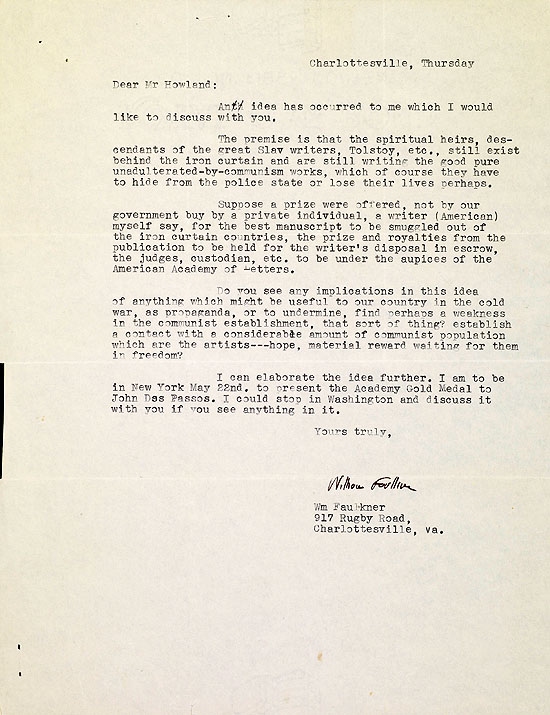

, though he also considered sponsoring a literary prize for “the best

manuscript to be smuggled out of the iron curtain countries.” Not long after the 1957-1958 academic year began, the

Russians launched Sputnik, the first man-made object to orbit the earth. As the 180-pound satellite passed through the skies over

America, millions of people watched and could not help thinking about those Soviet tanks in Hungary. The Cavalier Daily

closely covered the story of Sputnik, as well as the failures and successes of the fledgling American space program. Space

immediately became the new theater of Cold War operations. NASA, for example, was created in 1958. Fears about potential Soviet

superiority in science and technology had direct consequences for higher education in this country, when the National Defense

Education Act was passed at the start of the 1958-1959 school year to provide colleges and universities with resources for

training American experts to compete with Russia’s.

, though he also considered sponsoring a literary prize for “the best

manuscript to be smuggled out of the iron curtain countries.” Not long after the 1957-1958 academic year began, the

Russians launched Sputnik, the first man-made object to orbit the earth. As the 180-pound satellite passed through the skies over

America, millions of people watched and could not help thinking about those Soviet tanks in Hungary. The Cavalier Daily

closely covered the story of Sputnik, as well as the failures and successes of the fledgling American space program. Space

immediately became the new theater of Cold War operations. NASA, for example, was created in 1958. Fears about potential Soviet

superiority in science and technology had direct consequences for higher education in this country, when the National Defense

Education Act was passed at the start of the 1958-1959 school year to provide colleges and universities with resources for

training American experts to compete with Russia’s.

To the student of pop culture, however, 1957 was also the year in which the Wham-O toy company launched its most successful

product: the Pluto Platter, which soon became known as the frisbee. There’s

no sign of this flying object in the CD, but according to John A. Church, Class of 1959, “the nationwide

Frisbee craze struck” UVA hard.

*

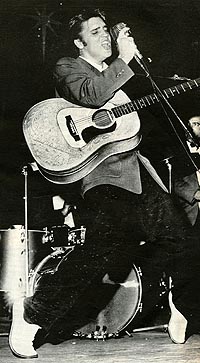

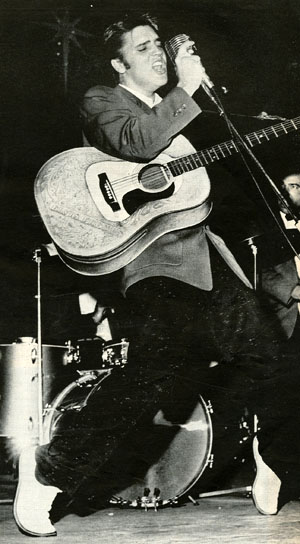

. Another cultural phenomenon that is surprisingly invisible in the student newspaper, and not brought up in

Faulkner’s sessions, is the emergence on the national stage of Mississipian Elvis Presley, whose appearances on

television in the Fall 1956 galvanized the country. Perhaps because UVA was so attached to the idea of tradition, or perhaps

because Faulkner’s novels say so much more about the southern past and the early Twentieth century than about the

immediate world of the late Fifties, the cultural issues that, for many historians, were symptomatically finding expression in

Elvis’ body language and the eruption of rock-n-roll are seldom audible on the tapes. At least, I can’t hear

any signs of a generation gap on them. Adults – or at least voices that sound as if they belong to adults –

ask a surprisingly large number of the questions; when the questioners sound like students, they almost invariably seem to ask the

same kind of questions that their teachers do. But the times were a-changing. Faulkner usually declines to talk at all about

“contemporary literature,” but does say he has read J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye

(1951), and shares with his listeners a sympathy for Holden Caulfield’s alienation from the times. And on two different

occasions the “San Francisco renaissance” is briefly discussed. Allen Ginsberg’s Howl came

out in 1956, and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road in 1957; Kerouac is mentioned by name, and the term “San

Francisco poets” clearly has meaning to a Charlottesville audience, though it sounds as if those people are uncertain

about what anyone should make of this new direction in American literature. Compared to the Beats’ public readings,

Faulkner’s are very decorous; as you listen to them, it’s not hard to see the jackets and ties on the men,

young and old, in his audiences.

To the student of pop culture, however, 1957 was also the year in which the Wham-O toy company launched its most successful

product: the Pluto Platter, which soon became known as the frisbee. There’s

no sign of this flying object in the CD, but according to John A. Church, Class of 1959, “the nationwide

Frisbee craze struck” UVA hard.

*

. Another cultural phenomenon that is surprisingly invisible in the student newspaper, and not brought up in

Faulkner’s sessions, is the emergence on the national stage of Mississipian Elvis Presley, whose appearances on

television in the Fall 1956 galvanized the country. Perhaps because UVA was so attached to the idea of tradition, or perhaps

because Faulkner’s novels say so much more about the southern past and the early Twentieth century than about the

immediate world of the late Fifties, the cultural issues that, for many historians, were symptomatically finding expression in

Elvis’ body language and the eruption of rock-n-roll are seldom audible on the tapes. At least, I can’t hear

any signs of a generation gap on them. Adults – or at least voices that sound as if they belong to adults –

ask a surprisingly large number of the questions; when the questioners sound like students, they almost invariably seem to ask the

same kind of questions that their teachers do. But the times were a-changing. Faulkner usually declines to talk at all about

“contemporary literature,” but does say he has read J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye

(1951), and shares with his listeners a sympathy for Holden Caulfield’s alienation from the times. And on two different

occasions the “San Francisco renaissance” is briefly discussed. Allen Ginsberg’s Howl came

out in 1956, and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road in 1957; Kerouac is mentioned by name, and the term “San

Francisco poets” clearly has meaning to a Charlottesville audience, though it sounds as if those people are uncertain

about what anyone should make of this new direction in American literature. Compared to the Beats’ public readings,

Faulkner’s are very decorous; as you listen to them, it’s not hard to see the jackets and ties on the men,

young and old, in his audiences.

Images of current events from The Cavalier Daily —

Articles about current events from The Cavalier Daily —

- Anti-Integration Blast Rocks Clinton Negroes (28 September 1956)

- Eisenhower, Nixon Win in School Election (18 October 1956)

- Hungarians Clash with Russia in Bitter Civil War Conflicts (25 October 1956)

- Darden Asks Observance for Hungary (31 October 1956)

- Crucial Test for the U. N. (8 November 1956)

- Clinton Classroom Integrated Quietly (11 December 1956)

- Ike's Middle East Plan Devised to Stop War (8 January 1957)

- Senator McCarthy (4 May 1957)

- 1000 Arkansas Whites Riot As Negroes Enter School (24 September 1957)

- Eisenhower Orders Federal Troops To Little Rock (25 September 1957)

- Young Men on the Left (29 October 1957)

- [Letter to Editor about "Young Men on the Left"] (6 November 1957)

- Dulles Admits Russia Ahead (6 November 1957)

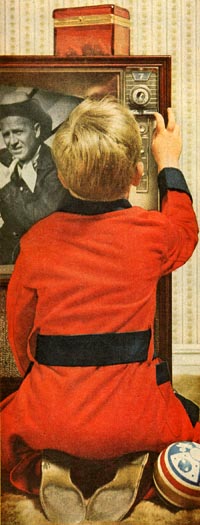

Below: Detail from full-page ad for General Electric's new model TV set, as published in Life magazine, 1 October 1956: 14.

Below: photograph by Michael Rougier of Soviet Russian tanks in the streets of Budapest, 1958 (Keystone Press Agency).

The Cavalier Daily 4 May 1957: 2

Senator McCarthy

Senator Joseph R. McCarthy died Thursday evening at Bethesda Naval Hospital of acute hepatitis. Thus ended one of the most controversial Senate careers in the history of American politics.

Whatever can be said of Senator McCarthy's Senate record or of him personally, we should never overlook the service he did to this country in exposing the menace of international communism within the framework of our national government.

Senator McCarthy's philosophy used in uncovering communists during his investigations seemed to be that the ends justified the means. At times, this policy leads to more trouble than good but in this case, where national security was in the gravest jeopardy, it is possible that the Senator's procedure was the only way to wake up the people and get a reform movement under way.

His death will be remembered as a great loss to the American people and the free world's fight against international communism.

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

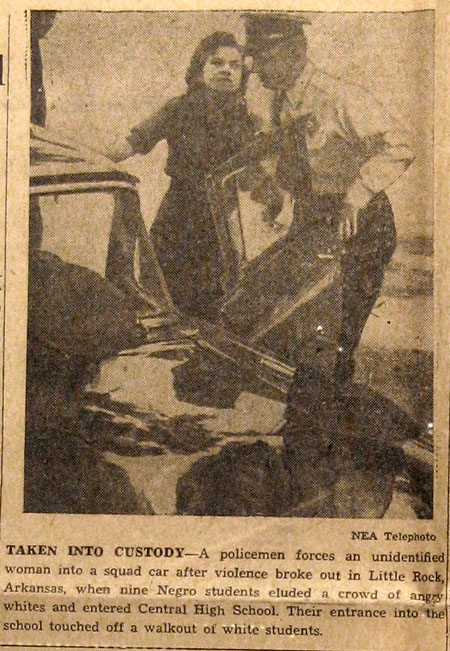

Below: photographs by Francis Miller of attempts to integrate Central High School, Little Rock, Arkansas, as published in Life magazine, 16 September 1957: 27, 24. Captions: (left) "TURNED AWAY from Little Rock's Central High School, Elizabeth Eckford is waved off by guardsmen. She later tried again to pass through lines"; (right) "JEERS FROM A GIRL, Hazel Bryant, follow Elizabeth Eckford as she walks from Central High. Guardsmen barred her from school." The soldiers in these photos were Arkansan National Guard troops, mobilized by Gov. Faubus to prevent black students from entering the school. A few days later Pres. Eisenhower sent Army troops into Little Rock, both to protect the black students and to see that, as ordered by federal courts, they were allowed to attend the school (bottom, Bettman Corbis).

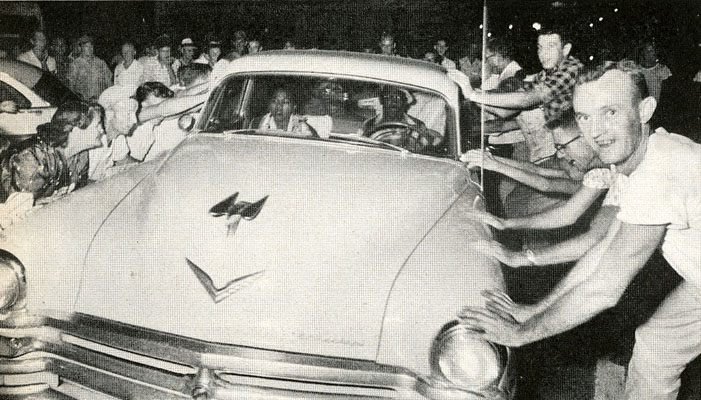

Below: photograph by Robert W. Kelley taken outside Clinton (Tennessee) High School, as published in Life magazine, 17 September 1956: 36. Caption: "HARASSING NEGROES, a mob, which included women, rocks an out-of-state car passing through Clinton. For four hours the town police stood by helpless as cars were dented and windows smashed. The Negroes were roughed up. A policeman persuaded part of mob to attack only Tennessee cars."

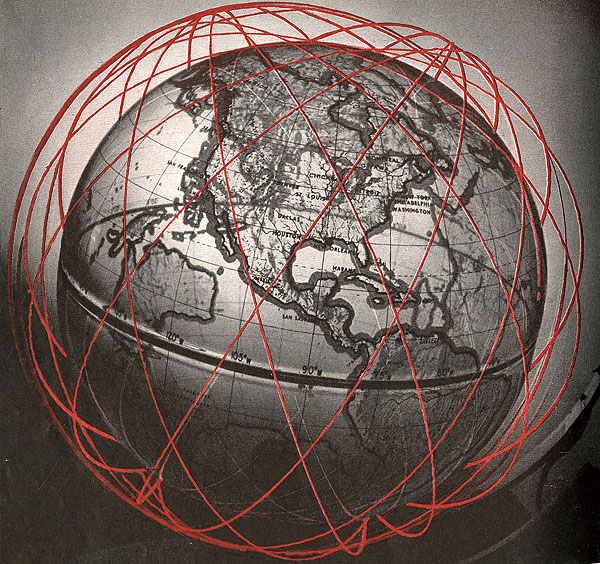

Below: graphic published by Life magazine, 1 October 1956: 24. Caption: "THE ORBIT WEAVES A WEB AS WHOLE WORLD WATCHES. PATTERN OF ORBITS traced by Sputnik in typical 24-hour period is demonstrated by red bulb going around globe built by Robert H. Farquhar. Earth rotates from west to east (left to right) and position of orbits (red lines) shifts west each time satellite goes around earth. At noon, orbit passes just east of Florida, going northwest to southeast. It appears 96 minutes later over western U.S. After midnight when earth has turned around so U.S. is on reverse side of globe in picture, orbit goes from southwest to northeast, passing through Midwest and, 96 minutes later, through California."

Below: Letter from William Faulkner to Harold Howland, c. 9 May 1957 (per envelope), about an idea for a literary prize he might offer to "best manuscript to be smuggled out of the iron curtain countries." Faulkner Papers, UVA Special Collections [Digitization #000003743_0031].

Below: Photo by Dan Fagar of Elvis Presley, as published in Life magazine, 27 August 1956: 103 (Gilloon Agency). Caption: GYRATING HOWLER swings both guitar and hips in a tip-toe version of the burlesque bump he uses."

Church, Pleasant Riches: The University of Virginia in the Late Fifties (Princeton Junction: PDQ Press, 2009): 23. Church's chapter on Faulkner's presence at UVA is available, in part, in the Introduction to this archive.

The Cavalier Daily 28 September 1956: 1, 4

Anti-Integration Blast Rocks Clinton Negroes

CLINTON, TENN., Sept. 27—(U.P.)—Officers today called an explosion that rocked this town's Negro community an effort to intimidate parents who send their children to integrated Clinton High School.

Sheriff Glad Woodward expressed fears that the blast, which caused little damage, was part of a "continuing series" of anti-Negro incidents that reached a climax in tumultuous rioting less than a month ago.

The explosions, believed set off by dynamite packed in two beer cans, tore a six-inch hole last night in the ground of a vacant lot and shattered a window n [sic] one nearby house.

Woodward said he believed the explosion was intended to "throw a fright" into Negroes. Officers have reported stepped-up meetings of pro-segregation groups in the county.

"It looks like a case of intimidation," chief deputy sherrif Robert Arnett said. The explosion "could just as easily have been thrown into somebody's front yard."

The father of one of the Negro pupils enrolled at the school was arrested shortly after the blast and charged with carrying a weapon. He was identified as Herbert Allen, about 40, the father of JoAnn Allen, a junior.

A window was shattered in the house of Sterling Weaver, a rail-road employee. The explosion showered dirt and debris on the homes of Ronald Hayden and Rev. O. W. Willis. Hayden's son Ronnie is a student at Clinton High School.

Officers said the blast blew a fence post 40 feet and rattled windows throughout this city of 4,000 population. Allen was going to the site of the explosion to investigate when officers picked him up.

Arnett said Allen apparently had "some idea of being ready to defend his home." He was charged with carrying a .38 pistol and released under $250 bond, Arnett said.

Twelve Negro children who were admitted to the school Au. 27 under a federal court integration order showed up for classes today.

Their attendance sparked unruly demonstrations and mob activity that had to be quelled by Tennessee National Guardsmen sent in by Governor Frank Clement during the labor day weekend.

A headwaiter at a restaurant in nearby Oak Ridge, Allen is considered to be of good reputation. His daughter, 14 year old Jo Ann, and a white classmate appeared on a television panel show Sunday at Washington with U. S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Jr. Jo Ann is vice-president of her homeroom.

Meanwhile at Mobile, Alabama, city police and a state fire marshal studied the apparent arsonist burning of a Negro's home in a white neighborhood. The home of Booker T. Gulley, 37, was damaged last night after the Negro and his family had left the house because three shotgun blasts were fired into it earlier in the day.

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 18 October 1956: 1

Eisenhower, Nixon Win in School Election

Republicans Receive Clear Vote Majority

Total Vote of 1107 Is Larger in Comparison to Past Elections

Receiving 64 percent of the ballots cast, Eisenhower and Nixon won a clear majority of votes in the Cavalier Daily Presidential Preference Election completed yesterday afternoon. The Republican ticket took 714 votes, Democrats 294, and States Rights, 99

The total vote was 1107 out of an enrollment of 4346 at the University. The number was considered high in comparison with past elections here. Last year's total for the Pogo-Peanuts ballot was only 683.

The margin between Eisenhowever and Stevenson was substantial with the Republicans taking a 2 to 1 majority. The Democrats won about 2 to 1 over the independent States Righters under T. Coleman Andrews of Richmond.

Preference for the Andrews-Werdel States Rights candidates came largely from Virginia voters with several others submitted from Pennsylvania, West Virginia, South Carolina and elsewhere.

The vote came at the climax of a special series of articles bringing out facts in the platforms and plans of the two major parties. Four articles appeared in the series. The first presented personal accounts of each principal candidate, the second, platforms of the Republican and Democratic parties, third, statements by the chairmen of the local political groups and last, summaries of the platforms and party policies.

Voters were offered the choice between the Eisenhower-Nixon and Stevenson-Kefauver tickets with the option of writing in any other candidates chosen. Andrews and Werdel votes were written in.

The "relatively good" showing of the Andrews-Werdel combination came as a surprise to many considering the fact that the States-Rights Party had begun its campaign only this week.

As usual in University elections, various "crank ballots" were submitted among the legitmate ones. A male, aged 25, College student from Virginia voted "for anyone who would get the coeds out of U.Va." Adlai Stevenson picked up "Peanuts" as a running mate for the Number 2 spot. Charlie Brown received one vote for President, Linus, one for President and another for Vice-President, and President [sic].

General Douglas McArthur was placed on a ticket with Eisenhower as Vice-President. Colgate Darden, President of the University, won one vote with the second spot being given to Bob Eggleston, Editor of the Cavalier Daily, and one vote was registered for Senators McCarthy and Jenner for President and Vice-President in that order.

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 18 October 1956: 1

Eisenhower, Nixon Win in School Election

Republicans Receive Clear Vote Majority

Total Vote of 1107 Is Larger in Comparison to Past Elections

Receiving 64 percent of the ballots cast, Eisenhower and Nixon won a clear majority of votes in the Cavalier Daily Presidential Preference Election completed yesterday afternoon. The Republican ticket took 714 votes, Democrats 294, and States Rights, 99

The total vote was 1107 out of an enrollment of 4346 at the University. The number was considered high in comparison with past elections here. Last year's total for the Pogo-Peanuts ballot was only 683.

The margin between Eisenhowever and Stevenson was substantial with the Republicans taking a 2 to 1 majority. The Democrats won about 2 to 1 over the independent States Righters under T. Coleman Andrews of Richmond.

Preference for the Andrews-Werdel States Rights candidates came largely from Virginia voters with several others submitted from Pennsylvania, West Virginia, South Carolina and elsewhere.

The vote came at the climax of a special series of articles bringing out facts in the platforms and plans of the two major parties. Four articles appeared in the series. The first presented personal accounts of each principal candidate, the second, platforms of the Republican and Democratic parties, third, statements by the chairmen of the local political groups and last, summaries of the platforms and party policies.

Voters were offered the choice between the Eisenhower-Nixon and Stevenson-Kefauver tickets with the option of writing in any other candidates chosen. Andrews and Werdel votes were written in.

The "relatively good" showing of the Andrews-Werdel combination came as a surprise to many considering the fact that the States-Rights Party had begun its campaign only this week.

As usual in University elections, various "crank ballots" were submitted among the legitmate ones. A male, aged 25, College student from Virginia voted "for anyone who would get the coeds out of U.Va." Adlai Stevenson picked up "Peanuts" as a running mate for the Number 2 spot. Charlie Brown received one vote for President, Linus, one for President and another for Vice-President, and President [sic].

General Douglas McArthur was placed on a ticket with Eisenhower as Vice-President. Colgate Darden, President of the University, won one vote with the second spot being given to Bob Eggleston, Editor of the Cavalier Daily, and one vote was registered for Senators McCarthy and Jenner for President and Vice-President in that order.

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 25 October 1956: 1

Hungarians Clash with Russia in Bitter Civil War Conflicts

Police Encourage Inflamed Rioters; 350 Persons Are Reported Killed

VIENNA, Oct. 24.—(U.P.)—Hungarians battled Russian troops and tanks and Soviet-built MIG jets in a civil war in the streets of Budapest today for their freedom. Fighting raged on past two Hungarian government cease-fire ultimatums.

Eyewitnesses reports said at least 350 persons had been killed in the fighting which erupted last night. Radio Budapest broadcast appeals for help in bringing wounded to hospitals. It admitted government forces were on the "defensive."

Not even the emergency appointment of popular "Titoist" Imre Nagy as premier this morning replacing Stalinist Andras Hegedues could stop the inflamed people.

There were indications that elements of the Hungarian army were fighting on the side of the rebels.

Soldiers Cheer

Travelers returning from the embattled city said that in the early phases of the fighting many police and Hungarian soldiers stood by and cheered the Rebels.

Thousands of demonstrators faced the blazing guns of the Russians and the government-controlled Hungarian army to scream "go home, Russians."

The government radio was forced to explain in answer to "many questions" that the Russians were in Hungary solely because Hungary is a member of the Warsaw mutual defense pact (Russia's answer to the NATO pact in the west).

Priests, labor leaders, former government officials, even the father of a captured rebel, were put on the air to appeal for an end to the fighting.

Deadline Extended

Premier Nagy's frantic appeals for order were disregarded. He proclaimed a 2 p.m. (9 a.m. EDT) deadline for citizens to stop fighting without penalty or else face executions. The deadline had to be extended four hours to 6 p.m.

The state radio, which has been the only means of communications with Hungary since the fighting flared last night, said rebels had tried to take the magnesium mines at Tathanya and Salgotarjan northwest of the city but had been repulsed.

The eyewitness said he understood the fighting had spread throughout the country.

Budapest residents "are convinced that people also are revolting against the regime in the cities of Debrecenlin, Szolnok and Szeged," he reported.

He said he saw "at least 350 people dead" in the city, including soldiers and civilians, as he left by car for the border.

The state radio reported that "counter-revolutionaries" fighting near the houses of Parliament had been strafed by jet planes.

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 25 October 1956: 1

Hungarians Clash with Russia in Bitter Civil War Conflicts

Police Encourage Inflamed Rioters; 350 Persons Are Reported Killed

VIENNA, Oct. 24.—(U.P.)—Hungarians battled Russian troops and tanks and Soviet-built MIG jets in a civil war in the streets of Budapest today for their freedom. Fighting raged on past two Hungarian government cease-fire ultimatums.

Eyewitnesses reports said at least 350 persons had been killed in the fighting which erupted last night. Radio Budapest broadcast appeals for help in bringing wounded to hospitals. It admitted government forces were on the "defensive."

Not even the emergency appointment of popular "Titoist" Imre Nagy as premier this morning replacing Stalinist Andras Hegedues could stop the inflamed people.

There were indications that elements of the Hungarian army were fighting on the side of the rebels.

Soldiers Cheer

Travelers returning from the embattled city said that in the early phases of the fighting many police and Hungarian soldiers stood by and cheered the Rebels.

Thousands of demonstrators faced the blazing guns of the Russians and the government-controlled Hungarian army to scream "go home, Russians."

The government radio was forced to explain in answer to "many questions" that the Russians were in Hungary solely because Hungary is a member of the Warsaw mutual defense pact (Russia's answer to the NATO pact in the west).

Priests, labor leaders, former government officials, even the father of a captured rebel, were put on the air to appeal for an end to the fighting.

Deadline Extended

Premier Nagy's frantic appeals for order were disregarded. He proclaimed a 2 p.m. (9 a.m. EDT) deadline for citizens to stop fighting without penalty or else face executions. The deadline had to be extended four hours to 6 p.m.

The state radio, which has been the only means of communications with Hungary since the fighting flared last night, said rebels had tried to take the magnesium mines at Tathanya and Salgotarjan northwest of the city but had been repulsed.

The eyewitness said he understood the fighting had spread throughout the country.

Budapest residents "are convinced that people also are revolting against the regime in the cities of Debrecenlin, Szolnok and Szeged," he reported.

He said he saw "at least 350 people dead" in the city, including soldiers and civilians, as he left by car for the border.

The state radio reported that "counter-revolutionaries" fighting near the houses of Parliament had been strafed by jet planes.

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 31 October 1956: 1

Darden Asks Observance for Hungary

Joining other leading colleges and universities around the nation, the University will honor the Hungarian students who have risen against Soviet domination by suspending all activities for two minutes at noon tomorrow. This observance is being held at the request of Colgate W. Darden, president of the University.

The American Committee for Cultural Freedom, through its chairman, Diana Trilling, sent President Darden a telegram asking for this action "in tribute to the Hungarian students who have made a sacrifice so meaningful to us in our democracy."

"The University students of Hungary who have played such a leading role in the struggle of their countrymen against Soviet tyranny and for freedom have deeply stirred the minds and hearts of free people everywhere," Miss Trilling's message said. "Their heroic action exposes the reality of Soviet imperialism, and represents the most serious challenge yet offered to Communism by people behind the Iron Curtain."

President Darden telegraphed in reply, "I am in complete accord with your desire to pay tribute to the University of Hungary and all others there who have joined in the resistance to Soviet tyranny and I shall ask that there be a suitable observance at the University of Virginia."

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 31 October 1956: 1

Darden Asks Observance for Hungary

Joining other leading colleges and universities around the nation, the University will honor the Hungarian students who have risen against Soviet domination by suspending all activities for two minutes at noon tomorrow. This observance is being held at the request of Colgate W. Darden, president of the University.

The American Committee for Cultural Freedom, through its chairman, Diana Trilling, sent President Darden a telegram asking for this action "in tribute to the Hungarian students who have made a sacrifice so meaningful to us in our democracy."

"The University students of Hungary who have played such a leading role in the struggle of their countrymen against Soviet tyranny and for freedom have deeply stirred the minds and hearts of free people everywhere," Miss Trilling's message said. "Their heroic action exposes the reality of Soviet imperialism, and represents the most serious challenge yet offered to Communism by people behind the Iron Curtain."

President Darden telegraphed in reply, "I am in complete accord with your desire to pay tribute to the University of Hungary and all others there who have joined in the resistance to Soviet tyranny and I shall ask that there be a suitable observance at the University of Virginia."

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 8 November 1956: 2

Crucial Test for the U. N.

In the peoples' revolt against the Communist government of Hungary, the United Nations has found the issue upon which it must stand or die. It is an issue which far over shadows the Egyptian war simply because it is one which finds the civilized world pitted against its greatest menace, against its greatest test – the Soviet Union.

In Hungary, the people of a whole nation have risen as a single body and, without planned coordination, without assistance from the outside world, with nothing beyond the insuppressable spirit of liberty and patriotism, has driven a puppet government, along with all that government's supporting Russian troops from national power. The revolution was complete on Saturday. On Sunday, it was reversed by the treacherous tactics of Communist Russia which, under pretense of negotiation for the withdrawal of Russian troops, captured leaders of the insurrection and restored Hungary to hated Communist rule under the compulsion of Communist guns and tanks. All Sunday, the free radio stations died, one by one, with last protests of the Soviet counterstroke and desperate calls for United Nations aid.

Sunday night, the UN answered with a strong resolution condemning the Russian move accompanied by an order for Soviet troops to halt their attack against Hungary. This is precisely how matters stand at the present time.

The order is one which, if not obeyed with deliberate speed, must be backed up immediately by positive and decisive force. The Soviet Union has violated the most fundamental of international laws. If this violation cannot be corrected by United Nations action, there is little reason for further existence.

Accordingly, the United States must back the United Nations with force – force in the form of U. S. manpower. This means placing American troops in the field against Russian troops, but, if it is the only way left to guarantee the final authority of the UN, then it is high time that such U. S. commitment be made. Any armed force supplied by this country should, of course, be used in the name of the UN and joined by forces from other UN nations.

Had such a course been adopted when Adolf Hitler overran eastern Europe in 1939, it is more than possible that World War II would not have been fought. By the same token, force against the Kremlin today might well prevent the disaster of a Third World War – a war which would most likely end the civilization we know today.

T[homas]. M. M[artin].

(Editor's Note: Due to a split in opinion within the Managing Board, this article has not been given editorial status.)

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 8 November 1956: 2

Crucial Test for the U. N.

In the peoples' revolt against the Communist government of Hungary, the United Nations has found the issue upon which it must stand or die. It is an issue which far over shadows the Egyptian war simply because it is one which finds the civilized world pitted against its greatest menace, against its greatest test – the Soviet Union.

In Hungary, the people of a whole nation have risen as a single body and, without planned coordination, without assistance from the outside world, with nothing beyond the insuppressable spirit of liberty and patriotism, has driven a puppet government, along with all that government's supporting Russian troops from national power. The revolution was complete on Saturday. On Sunday, it was reversed by the treacherous tactics of Communist Russia which, under pretense of negotiation for the withdrawal of Russian troops, captured leaders of the insurrection and restored Hungary to hated Communist rule under the compulsion of Communist guns and tanks. All Sunday, the free radio stations died, one by one, with last protests of the Soviet counterstroke and desperate calls for United Nations aid.

Sunday night, the UN answered with a strong resolution condemning the Russian move accompanied by an order for Soviet troops to halt their attack against Hungary. This is precisely how matters stand at the present time.

The order is one which, if not obeyed with deliberate speed, must be backed up immediately by positive and decisive force. The Soviet Union has violated the most fundamental of international laws. If this violation cannot be corrected by United Nations action, there is little reason for further existence.

Accordingly, the United States must back the United Nations with force – force in the form of U. S. manpower. This means placing American troops in the field against Russian troops, but, if it is the only way left to guarantee the final authority of the UN, then it is high time that such U. S. commitment be made. Any armed force supplied by this country should, of course, be used in the name of the UN and joined by forces from other UN nations.

Had such a course been adopted when Adolf Hitler overran eastern Europe in 1939, it is more than possible that World War II would not have been fought. By the same token, force against the Kremlin today might well prevent the disaster of a Third World War – a war which would most likely end the civilization we know today.

T[homas]. M. M[artin].

(Editor's Note: Due to a split in opinion within the Managing Board, this article has not been given editorial status.)

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 11 December 1956: 1

Clinton Classroom Integrated Quietly

CLINTON, Tenn., Dec. 10—(U.P.)—Eight Negro children and 591 whites returned quietly to integrated Clinton High School today ending a five day classroom shutdown caused by racial strife.

Students returned without incident and when school was dismissed at 3:30 p.m. they also went home without trouble. The eight negro students gathered outside the main entrance and walked unescorted to Foley Hill where they live.

One negro, asked how things went today, replied "just fine."

Meanwhile at Knoxville, 20 miles to the southeast, 16 persons pleaded innocent in U.S. District Court to instigating anti-integration activities at the school in violation of a federal injunction.

Judge Robert L. Taylor set their trials for the week of Jan. 28. Defense attorneys indicated the sympathetic Dixie officials were ready to make a major legal stand against the breakdown of segregation barriers in the south.

The attorneys for the defendants moved orally to have the "whole proceeding" dismissed on grounds on the charges are "so indefinite that we don't know how to defend the case." Judge Taylor gave them until Jan. 12 to file written motions for dismissal.

The 16 persons, including two women, were rounded up by U.S. marshals last week after a white Baptist preacher was beaten for escorting Negroes to school and teen-age segregationists tried to invade classrooms to "get those niggers."

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 8 January 1957: 1, 4

Secretary Dulles Tells Congress

Ike's Middle East Plan Devised to Stop War

WASHINGTON, Jan. 7—(U.P.)—Secretary of State John Foster Dulles assured Congress today that President Eisenhower's new Middle East doctrine is designed "to stop World War III before it starts."

He told the House Foreign Affairs Committee that quick Congressional approval of the program would serve as a stern warning that this country is ready to use its military and economic strength to protect Mid-East nations from Communist seizure.

But Dulles promised that the administration would not use the requested authority simply to head off Communist subversion.

He said there is no thought of embracing a policy under which this country "would go around the world invading countries whose governments you don't like." Such a policy, he said, inevitably would lead to general war.

Committee Chairman Thomas Gordon (D-Ill.) said the Secretary's testimony "cleared up many points" and may enable the committee "to take final action even sooner than it was originally expected."

Senate Republican Leader William F. Knowland (Calif.) predicted Congress will approve the "fundamental concept" of the plan although it may make some changes.

"The President will not be repudiated in this matter," he said.

Dulles said there always is danger that Mid-East nations may fall into the Soviet orbit through open military attack, internal subversion, or through chaotic economic conditioning which would make Communism look attractive.

The loss of the Mid-East, he said, would be a "major disaster" for the free world and would encourage Communists everywhere to resort to more aggressive tactics.

He said that until Congress endorses the new program, there will be doubts in both the Mid-East and in Russia that the United States really means what it says. He cautioned that "if the doubts persist, then the danger persists and grows."

"The purpose of the proposed resolution is not war," he said. "It is peace. The purpose, as in the other cases where the President and the Congress have acted together to oppose international Communism, is to stop World War III before it starts."

Dulles was the opening witness at the committee's hearing on the new Mid-East policy, outlined to Congress by Mr. Eisenhower at an unusual joint session last Saturday.

Mr. Eisenhower asked for stand-by authority to use American troops, if necessary, to guard any Mid-East nation which seeks U.S. protection against armed agression by Russia or a Russian-dominated nation.

He also asked for permission to supply military and economic aid to the area at a rate of about $600 million over the next three years.

The White House, in an evident bid for bipartisan support for the plan, announced today that former Rep. James P. Richards (D.-S.C.) has been appointed Mr. Eisenhower's special assistant on Middle Eastern affairs.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 4 May 1957: 2

Senator McCarthy

Senator Joseph R. McCarthy died Thursday evening at Bethesda Naval Hospital of acute hepatitis. Thus ended one of the most controversial Senate careers in the history of American politics.

Whatever can be said of Senator McCarthy's Senate record or of him personally, we should never overlook the service he did to this country in exposing the menace of international communism within the framework of our national government.

Senator McCarthy's philosophy used in uncovering communists during his investigations seemed to be that the ends justified the means. At times, this policy leads to more trouble than good but in this case, where national security was in the gravest jeopardy, it is possible that the Senator's procedure was the only way to wake up the people and get a reform movement under way.

His death will be remembered as a great loss to the American people and the free world's fight against international communism.

©1956 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 8 24 September 1957: 1

1000 Arkansas Whites Riot As Negroes Enter School

By The United Press

LITTLE ROCK, Ark., Sept. 23.—A spitting, cursing crowd which beat four Negro newsmen and surged against police lines, today cut short an attempt by nine Negro pupils to attend Central High School

The nine students slipped into the school unnoticed by a mob of perhaps 1,000 persons, but three hours later they left on orders of the mayor.

The Negro newsmen who were beaten turned up in front of the school at almost the same time the nine children entered by a back door at about 8:55 a.m. their time.

The outburst of violence, one of the worse since the Supreme Court outlawed segregation in 1954, was touched off by a little white girl who ran down the school steps screaming:

"They're in, they're in."

Her mother seized her by the hand and shouted:

"Let's go in and get the bastards."

What followed was three hours of struggle between police trying to keep order and white persons shouting curses at Negroes. Mothers shrieked for help in getting their children out of the school. A shovel was hurled at a Negro on a passing truck. A white woman collapsed with a heart attack and was taken away in an ambulance. At least 12 persons were hauled off in police patrol wagons. Among them were two kicking, screaming teen-aged girls who left school in protest against being in the same room with Negroes.

The Negroes were snubbed inside the school, but they were not harmed. One white girl told how a Negro girl was barred from a gym class by white girls who called her a "dirty Negro" and "black bitch."

A white boy told Minnie Brown, one of the Negroes, "Black gal, you don't belong here."

Outside, striking students joined their elders behind the police barricades. Angry adults spat and slapped cameramen and reporters.

"Get a rope . . . hang him . . . kill the black s.o.b.," members of the mob yelled at one of the Negro newsmen who turned up in front of the school.

"Nigger, you're not going to pass here!" someone yelled. "Block 'em, block 'em."

Mothers on the sidewalk started screeching: "I want my children out! I want my children out!"

When the crowd attacked the four Negro newsmen one was knocked down, kicked and beaten. Another was knocked down. And a third was kicked.

Four white reporters also were attacked. A man punched Bob Welsh of Time-Life.

Other newsmen were spat at and kicked as they tried to cover the effort to integrate Central High.

Calm finally was restored when Mann announced the Negroes had been taken out of the school.

Within a short time, the crowd broke up and by mid-afternoon children were playing softball on the school grounds.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 25 September 1957: 1, 4

Eisenhower Orders Federal Troops To Little Rock

Paratroops Are Rushed To Scene Of Strife, National Guard Federalized

WASHINGTON, Sept. 24—President Eisenhower ordered federal troops into Little Rock, Ark., Tuesday to force compliance with court-ordered integration of the city's Central High School.

Moving swiftly to carry out the President's orders, the Army rushed 500 paratroopers from the Elite 101st Airborne Division from Fort Campbell, Ky., to Little Rock. They were flown in Air Force transports to the scene of the integration disorders.

Eisenhower authorized use of the regular Army troops in an order that called the Arkansas National Guard into federal service to quell riotous obstruction of the school desegregation order handed down by a federal judge at Little Rock.

Defense Secretary Charles E. Wilson drew up the necessary orders carrying out the President's mandate, and Army Secretary Wilber M. Brucker was given full authority to act in the integration crisis.

They placed Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker, commander of the Arkansas military district, in charge of the federalized Arkansas guardsmen. Walker is a paratrooper and an Army ranger.

The President issued his historic order at Newport, R. I., before flying to Washington to deliver a nationwide radio-television report explaining his drastic action. All four networks carried the address last night.

The force of Airborne troops is three times the size of the Little Rock police force, which was not able to insure the integration of Central High.

Eisenhower stepped into the Arkansas crisis after a muttering crowd lined up before the Little Rock School again this morning even though nine negro students failed to show up. The negros slipped into the school yesterday but later were withdrawn.

At Little Rock, the head of the Arkansas NAACP, Mrs. L. C. Bates, said the children would attend Central High School tomorrow if the Federal Government could protect them from violence.

Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and the state's Air National Guard. The Guard, commanded by Brig. Gen. John W. Webb of Little Rock, has a strength of 9,936 men – 8,605 in the Army and 1,331 in the Air Army.

The President also authorized the Defense Secretary to draw on regular U. S. Armed Forces if they are needed to force compliance with the Federal Court order calling for integration of the high school. The troops would see that the negroes were admitted to the school.

Eisenhower said in his executive order that he acted because the Little Rock mob had failed to obey his earlier order to "cease and desist" its "wilful obstruction of justice."

He directed Wilson to order the Arkansas Guard into "the active military service of the United States for an indefinite period and until relieved by appropriate orders."

The President ordered Wilson to "take all appropriate steps" to enforce orders of the District Court "for the removal of obstruction to justice in the State of Arkansas with respect to matters relating to enrollment and attendance at public schools" in Little Rock.

Eisenhower and the White House also rejected claims by Arkansas Gov. Orval E. Faubus and others that he had no power to order troops into Little Rock unless the Governor requested them.

The President said he acted under "the Constitution and statutes of the United States, including chapter 15 of title 10, particularly sections 332, 333 and 334 thereof, and section 301 of title 3 of the United States code."

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 29 October 1957: 2

Young Men on the Left

We recently received the first number of an unusually obnoxious publication, staffed in the main by students of California's UCLA, and entitled, Young Socialist. Papers such as this one are nothing new in the United States, but we cannot but feel a little ripple of fear when we realize that those who write them are students like ourselves, and as such, are persons who should represent the best and most loyal in American society. That they do not is a cause for alarm, and a time to pause for a moment and to ask why.

The editor of this infant publication is a Communist without portfolio only. He does not carry the card, but of what significance is that when he carries the thinking, and has the ability to set forth that thinking in effective writing? He calls for the growth of a "broad and revitalized militant socialist youth movement that can act in a progressive way on the campuses and in the factories. . . ." His definition of acting "in a progressive way in the factories" is an interesting one. He says: "The workers themselves must democratically take over the management of industry and abolish the entire profit-making system."

The end result of such a worker's uprising he explains with the circular logic so characteristic of the Socialist. "Socialism," he continues, "means the direct control of the basic industries, not by an all-powerful bureaucracy, but by the people themselves, through their own organizations and the parties of their choice." Under such a system, of course, the only thing that would happen would be the exchange of power from one set of hands to another. Nothing would change for the worker. Men would still fight for shorter hours and longer pay, ad infinitum.

But we did not set out in this writing with a view toward attacking Socialist doctrines. We hate to see young people who, like ourselves, have had all the advantages of the American heritage. They, presumably, have come from homes of some means, and have enjoyed the benefits of a college education. But as thinkers they fall far short of the mark. As they proclaim their "brave new world" wherein the "dignity of man" will not be questioned, but refute all that they should rightfully hold dear. And in harboring the cancerous evil of Communism, they lay open the way for a world which, if new, will assuredly not be "brave," and in which the only thing that will not be questioned is the "dignity" of the Party.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

The Cavalier Daily 6 November 1957: 2

Letter to the Editor

Dear Sir:

Another of your warped and superficial editorials described this past week your difficulties in understanding why a group of students at UCLA is looking forward to a "broad and revitalized militant socialist movement." The reason, I would think, becomes distressingly obvious when you later state: "We hate to see young people who, like ourselves, have had all the advantages of the American heritage."

After waiting several days for a correction by you of the foregoing statement, which my faith insists was either a typographical mistake or a lapse of mind, none has been forthcoming.

Besides a certain sloppiness, the editorial is evidence that you are succumbing under the guise of anti-communism to a "creeping miasma of intimidation" that is already spreading its terrible shadow over the free world. There is no gain if the democracies, having achieved a full measure of religious toleration, should relapse into severe political orthodoxy. It is particularly repellent when local governments, companies, universities, and other bodies, take upon themselves the gratuitous duty of probing into the beliefs of their employees. The totalitarian and conformist spirit is abroad in the West, notably in the United States, a country where above all others it should find no home, whose chief traditions are dissent and variety. It is sad and disturbing to see the wealthiest and most powerful liberal society in the world so lacking in a sense of security and self-confidence that it appears to all its friends abroad to be frightened far more by "subversive" ideas than by real dangers of espionage.

When you believe that the Californian students' radical thinking shows lack of thought, you are demonstrating a failure to gather from your own education that every effort to confine Americanism to a single pattern, to constrain it to a single formula, is disloyalty to everything that is valid in Americanism. In training for the duties of citizenship maybe your mind has been wrapped in cotton-wool, and consequently your dismay at young American socialists reeks of an abandonment of evolution, of the once popular concept of progress, and implies that America is a finished product, perfect and complete.

Lastly, in regard to the selfishness and blind conformity of your over-all position on women, integration, and political beliefs, may I quote the words of an alumnus of this university, the late President Woodrow Wilson:

If there is one thing we love [in the United States], it is that every man should have the privilege, unmolested and uncriticized, to utter the real convictions of his mind. I believe that the weakness of the American character is that there are so few growlers and kickers among us. We have forgotten the very principle of our origin, if we have forgotten how to object, how to resist, how to agitate, how to pull down and build up even to the extent of revolutionary practices.

—Sheafe Satterthwaite

Editor's Note: Hitler, Stalin and Peron had their opinions also.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily

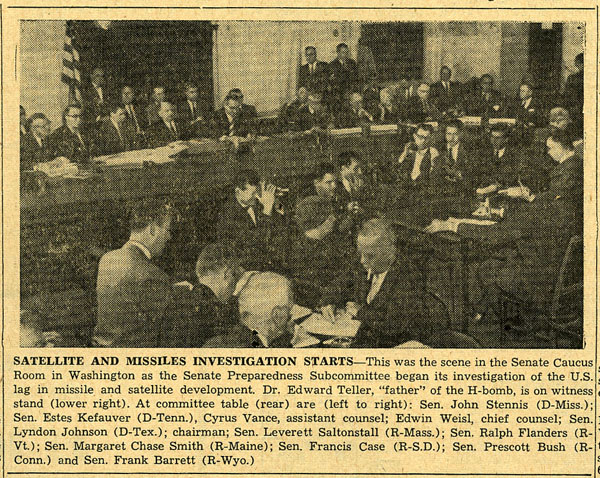

The Cavalier Daily 6 November 1957: 1

Dulles Admits Russia Ahead

TELETYPE ROUNDUP by United Press

WASHINGTON, Nov. 5—Secretary of State John Foster Dulles said today that Russia apparently is ahead of the United States in some areas of guided missile development. But he said he felt sure the United States could catch up.

Dulles told a news conference this country would demonstrate that it too can put a satellite into an orbit around earth. Presumably referring to the effect of the Soviet satellite on U. S. Allies, he said a U. S. satellite would be helpful psychologically.

The Secretary also said Russia's increased knowledge of weapons poses a danger so serious that the free nations have no alternative except to band closer together in their military and scientific programs.

He said the launching of Sputnik II confirmed U. S. suspicions that Russia now has the capability of making intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Dulles was asked if he thought the United States should have intermediate ballistic missiles in Europe in view of Russia's advances. He replied that this country already has such an agreement with Britain and believes it would be desireable to have others.

Missiles with a range of about 5,000 miles generally are considered in the intercontinental class. The same effect could be achieved, however, by ringing Russia with the shorter-range but equally deadly intermediate missiles.

©1957 The Cavalier Daily